2023 Volume 6 Issue 1

|

INEOS OPEN, 2023, 6 (1), 27–33 Journal of Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds Download PDF |

|

Composite Carbon Aerogels Containing Manganese Oxide:

Synthesis via Thermo-Oxidative Decomposition of Mn2(CO)10 in Supercritical CO2

a Faculty of Physics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Leninskie Gory 1, str. 2, Moscow, 119991 Russia

b Nesmeyanov Institute of Organolement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Vavilova 28, str. 1, Moscow, 119334 Russia

Corresponding author: V. I. Chernov, e-mail: chernov.vi19@physics.msu.ru

Received 16 August 2023; accepted 16 November 2023

Abstract

A new effective approach is suggested that allows for introducing nanosized highly dispersed particles of manganese oxide into carbon aerogels using the thermo-oxidative decomposition of Mn2(CO)10 dissolved in supercritical CO2. It is shown that the proposed procedure retains a branched porous structure of the material with a specific surface area of more than 600 m2/g. The resulting composite aerogels contain 4–16 wt % of manganese.

Key words: carbon aerogel, manganese oxide, supercritical CO2, manganese carbonyl, composite.

Introduction

Aerogels are porous materials with low density that can be obtained from gels by removing the liquid phase while maintaining the porous structure [1]. Among the variety of aerogels, carbon aerogels are distinguished by unusual properties, including an extremely high specific surface area and the ability to conduct electric current [2, 3]. In the first works describing the preparation and properties of carbon aerogels [4–6], the synthesis was carried out by supercritical drying of an organic gel followed by pyrolysis, while the organic gel was obtained by the condensation of resorcinol with formaldehyde. Despite the fact that this approach has been known for many decades, it is still actively used in research [7–9]. This synthetic approach ensures the independent control of the formation of pores of different sizes and the characteristic grain size of a three-dimensional porous structure by adjusting the synthesis conditions as needed. Carbon aerogels have certain applications, including the creation of functional materials for gas filtration [10], hydrogen adsorption and storage [11, 12], and use as electrodes for supercapacitors [13] and lithium-ion batteries [14].

The application scope of carbon aerogels can be expanded by modifying these materials. In particular, composite carbon aerogels containing manganese oxides, as was shown in a number of reports [15–21], have higher electrochemical activity than neat carbon aerogels. The presence of manganese oxide in the carbon matrix, as a rule, corresponds to lower specific surface area values than for neat carbon aerogels [18, 22], but, at the same time, leads to an increase in the mass-specific electric capacity of the carbon material. This facilitates the creation of highly efficient electrodes for supercapacitors based on MnOx/carbon aerogel composites, the characteristics of which depend both on the method of preparing the composite and on the amount of metal contained in it [17, 20]. It is worth noting that manganese-containing carbon aerogels can be used in some water purification tasks. Thus, the MnOx/carbon aerogel composites are not inferior in their ability to catalyze the decomposition of methylene blue than the manganese oxide catalysts deposited on other substrates [22]. In addition, Sánchez-Polo et al. [23] showed that the introduction of manganese derivatives into carbon aerogels significantly improves the photocatalytic performance of the material.

The existing methods for producing composite carbon aerogels containing metals or their derivatives from a solution of resorcinol with formaldehyde are based on the following concepts: the introduction of metal-containing compounds into the initial resorcinol–formaldehyde mixture [24], exposure of an intermediate organic gel in a solution containing a metal or its derivatives [25], and introduction into the preformed porous monolith with subsequent redistribution throughout the whole volume [26]. The production of the MnOx/carbon aerogel composites in the previous works was carried out by introducing manganese precursors into the initial solution of the reagents or by applying them to the formed carbon aerogel. Only a few reports deal with the quantitative investigation of the porosity of the resulting composites. Li et al. [18] obtained a composite material by the electrolysis of manganese(II) nitrate, where the carbon aerogel was used as a working electrode. The specific surface area of the resulting sample was 120 m2/g, which is several times less than the values typical for mesoporous carbon aerogels. Meng et al. [22] added resorcinol and formaldehyde to a dispersion of manganese(II) acetate, and the gels, obtained by the exposure of colloidal particles at a temperature of 60 °C, were pyrolyzed without preliminary supercritical drying. The resulting materials, differing in the manganese content, had specific surface areas of no more than 230 m2/g. Xu et al. [21] introduced N,N-dimethylmethanamide-coordinated MnO2 into the initial resorcinol–formaldehyde mixture. The samples formed contained predominantly mesopores; however, the pore size distribution significantly depended on the amount of introduced manganese, which complicated the control of the composite architecture. Wang et al. [27] managed to increase the specific surface area of a carbon aerogel containing manganese oxide by applying a silicon dioxide coating to nanosized particles of a resorcinol–formaldehyde gel, followed by drying and pyrolysis. The procedure involved several laborious steps and, due to the limited ability of silicon dioxide to penetrate into the aerogel pores, may not be suitable for repeating the result with macro-sized monoliths. Thus, the development of a more effective approach to doping carbon aerogels with manganese oxides remains an urgent experimental task.

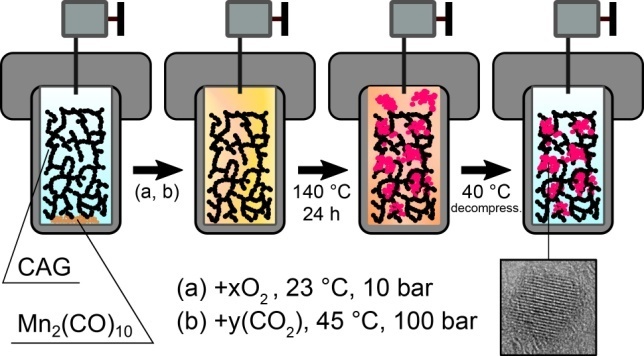

Recently, a new method for the synthesis of metal oxide aerogels has been proposed that is based on the thermal decomposition of the corresponding metal carbonyls in the presence of supercritical carbon dioxide [28–30]. According to this approach, a metal carbonyl is dissolved in oxygen-enriched supercritical CO2. Heating the solution above the carbonyl decomposition temperature leads to uniform nucleation and growth of nanoparticles of the corresponding metal oxide. It is important to note that due to the high solubility of metal carbonyls in supercritical CO2, the growth of nanoparticles occurs in a stable manner and the metal oxide phase occupies the entire volume of a high-pressure reactor. For manganese carbonyl, it was shown that this synthetic route leads to the formation of a three-dimensional monolithic aerogel with an extremely low density (about 5 mg/mL).

Since the characteristic size of the structural units of the resulting manganese oxide aerogel is several nanometers, the growth of the manganese oxide phase occurs throughout the entire free volume of the reactor, and the characteristic pore sizes of the carbon aerogel reach up to 50 nm, it can be assumed that metal oxide nanoparticles will be formed inside the porous carbon monolith if it is charged preliminarily into the synthesis reactor. Thus, a convenient and relatively fast in situ method for doping carbon aerogels with metal oxides can be elaborated.

The goal of this work was to obtain composite carbon aerogels containing manganese oxide using the thermo-oxidative decomposition of Mn2(CO)10 and to investigate the characteristics of the resulting composite materials.

Results and discussion

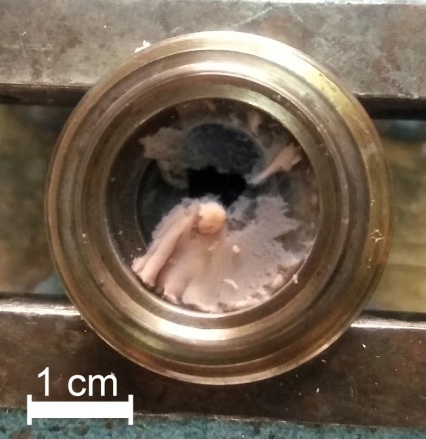

The experiments performed resulted in the production of composite materials based on carbon aerogels (for the detailed synthetic procedure, see, for example, Ref. [31]; the synthesis of the resorcinol–formaldehyde aerogels was described in Ref. [4]). The samples with the low Mn2(CO)10 loadings did not reveal any external changes. In contrast, at a relatively high loading of the carbonyl precursor (40, 50 mg) in the reactor outside the carbon aerogel, the formation of structures was observed (Fig. 1) that are identical in appearance and mechanical properties to the manganese oxide aerogels obtained in the absence of carbon aerogel [28].

Figure 1. Photograph of composite aerogel AG_Mn_4 obtained by the exposure of a carbon monolith with the addition of 40 mg of Mn2(CO)10 prior to the recovery from the reactor.

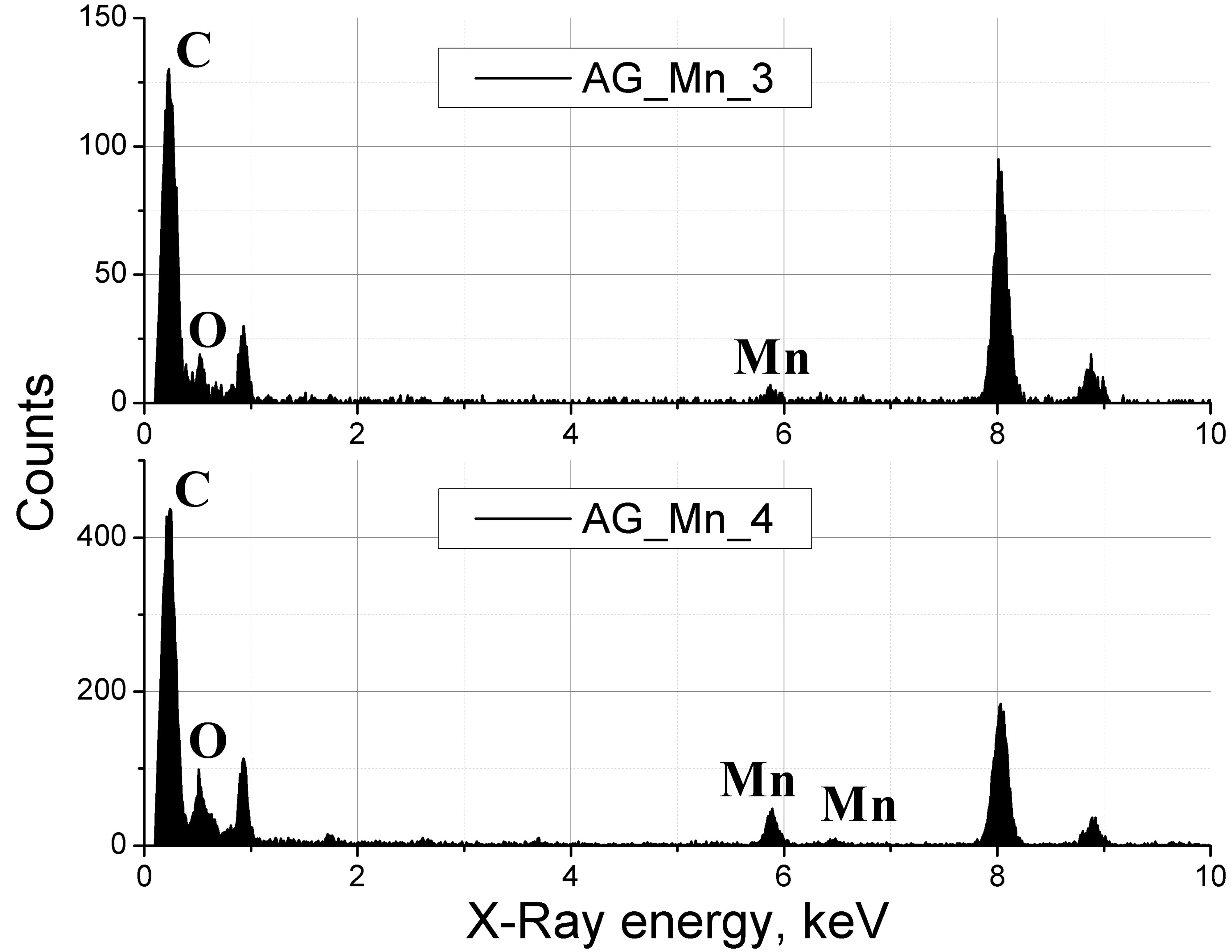

The contents of hydrogen, carbon wEA(C) and manganese wEA(Mn) in the resulting composites were determined by elemental analysis. The oxygen content wEA(O) was calculated as the remainder of the whole. The results obtained as well as the calculated mass fractions of the metal wtheor(Mn) are given in Table 1. The metal content was calculated as the ratio of the mass of manganese contained in the carbonyl sample to the mass of the composite. The found metal content wEA(Mn) does not differ significantly from the calculated value wtheor(Mn) and increases as the precursor loading increases. A small deviation of the experimental mass fraction of manganese from the calculated one shows that manganese contained in the carbonyl is either incorporated into the carbon matrix or remains in the carbon aerogel-free part of the reactor but does not leave the reactor upon decompression. The close values of wEA(Mn) obtained for spatially separated regions of the aerogel (as a consequence, a small spread of wEA) indicates high experimental reproducibility of the doping procedure. Taking into account the fact that, during the exposure of the aerogel together with the precursor, manganese is uniformly distributed throughout the reactor, it can be assumed that doping by thermo-oxidative decomposition of metal carbonyls provides a macroscopically uniform distribution of metal-containing particles throughout the volume of the carbon aerogel. The presence of the metal in the resulting composites is also confirmed by the analysis of the energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectra, the examples of which are shown in Fig. 2 (peaks in the region of 8–9 keV relate to the copper substrate which was used for the measurements). The fixation of manganese and its compounds on the surface of the carbon aerogel occurs, probably, due to interactions with unreacted hydroxy groups of resorcinol.

Table 1. Synthesis parameters, characteristics of the resulting composites based on the elemental analysis data, and comparison of the found metal contents with the calculated values. The reference carbon aerogel without additives is designated as CA

|

Sample

|

Mass of Mn2(CO)10,

mg |

Sample mass,

mg |

wEA(C),

%

|

wEA(O),

% |

wEA(Mn),

% |

wtheor(Mn),

% |

|

CA

|

0

|

–

|

|

|

–

|

–

|

|

AG_Mn_1

|

30

|

|

64.9

|

21.3

|

11.6±0.5

|

|

|

AG_Mn_2

|

20

|

62

|

74.2

|

16.3

|

8.1±0.1

|

9.6

|

|

AG_Mn_3

|

10

|

63

|

78.4

|

16.0

|

4.1±0.1

|

4.9

|

|

AG_Mn_4

|

40

|

68

|

60.3

|

27.4

|

10.7±0.5

|

11.7a

|

|

AG_Mn_5

|

50

|

71

|

59.7

|

23.2

|

15.3

|

14.9a

|

| a after deducting the mass of metal contained in formations outside the carbon monolith; the calculation was performed assuming that the structures outside the carbon aerogel consist entirely of MnO, which provided a lower estimate of the expected mass fraction wtheor. |

Figure 2. EDX spectra of samples AG_Mn_3–10 mg of the precursor and AG_Mn_4–40 mg of the precursor. Peaks at 8–9 keV correspond to the copper substrate which was used for the measurements.

Figures 3a–c depict the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the composites obtained. Their morphologies are similar to those of the carbon aerogels obtained previously with the same synthesis parameters [32]. The EDX spectra of the reference sample CA and composite AG_Mn_4 were used to obtain the mass fractions of the elements that make up the aerogels. The EDX analysis of the CA sample was performed through a standard study of a set of points and averaging of the resulting mass fractions. The averaged values are listed in Table 2. However, for AG_Mn_4, this approach gives a mass fraction of manganese equal to 22 ± 4 %, i.e., approximately twice as high as wEA(Mn) and wtheor(Mn). Moreover, the studied points are characterized by a significant (2–44%) spread of the measurement results. To clarify this result, the region of the sample bordering the reactor during the experimental procedures (external) and its part that emerged as a result of breaking (internal) were studied separately (Figs. 3b,c). The elemental maps were constructed for the internal region of the samples (Figs. 3d–f). It is obvious that, at the micrometer scale, the distribution of elements throughout the sample volume is significantly nonuniform. The same conclusion follows from a comparison of the mass fractions of manganese wS and wV given in Table 2, which were obtained for the different regions in the monolith. The values of wS and wV lie on the opposite sides and differ by approximately the same values from the found value of 10.7%, which, in principle, allows for a closer agreement between the results of the EDX and elemental analyses, provided that sufficient statistics are collected for the former. This heterogeneity in the distribution of the introduced manganese oxide phase may be due to both nonuniformity of the pores of the modified carbon aerogel itself and potential carbonyl and carboxyl functional groups on the surface of the carbon aerogel, which are able to better adsorb the introduced precursor [33].

Figure 3. SEM image of the reference sample (CA) (a); SEM image of the surface of sample AG_Mn_4 depicting the EDX measurement points (b); SEM image of the internal region of sample AG_Mn_4 (c). EDX maps for carbon, oxygen, and manganese measured for the AG_Mn_4 aerogel region shown in image (c), the scale of image c is preserved (d–f).

Table 2. Results of the EDX analysis

|

Sample

|

Region

|

Points explored

|

Counts

|

C,

wt % |

O,

wt% |

Mn,

wt % |

|

CA

|

|

10

|

105

|

73.6±0.8

|

25.5±0.8

|

–

|

|

AG_Mn_4

|

external

|

6

|

105

|

63.5±1.5

|

28.8±0.9

|

4.9±0.7a

|

|

internal

|

–

|

106

|

53.2±0.1

|

29.4±0.1

|

16.3±0.0b

|

| a wS designation; b wV designation. |

The branched porous structure of the composite carbon aerogels was confirmed by the results of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Fig. 4). A similar morphology was characteristic of the carbon aerogels synthesized in previous works [14, 19, 25, 26]; their transmission electron microscopy images are similar to those shown in Fig. 4. The morphology of the composites, in addition to the presence of manganese oxide particles, apparently does not differ from the morphology of the reference aerogel CA: the characteristic grain size of the carbon matrix and the appearance of the network do not change during the combined thermo-oxidative exposure with the carbonyl. The metal oxide particles in Fig. 4 are represented by local darkening, which are clearly observed in the images in the top row. The shapes of the particles, as well as in Refs. [15, 22, 27], are close to spherical; some particles are crystalline. Comparing three images (Fig. 4, top row), it can be assumed that the numerical concentration of the metal-containing particles increases with the increasing carbonyl precursor loading, and the particle size appears to decrease.

Figure 4. HRTEM images of samples CA (left), AG_Mn_2 (center), and AG_Mn_4 (right).

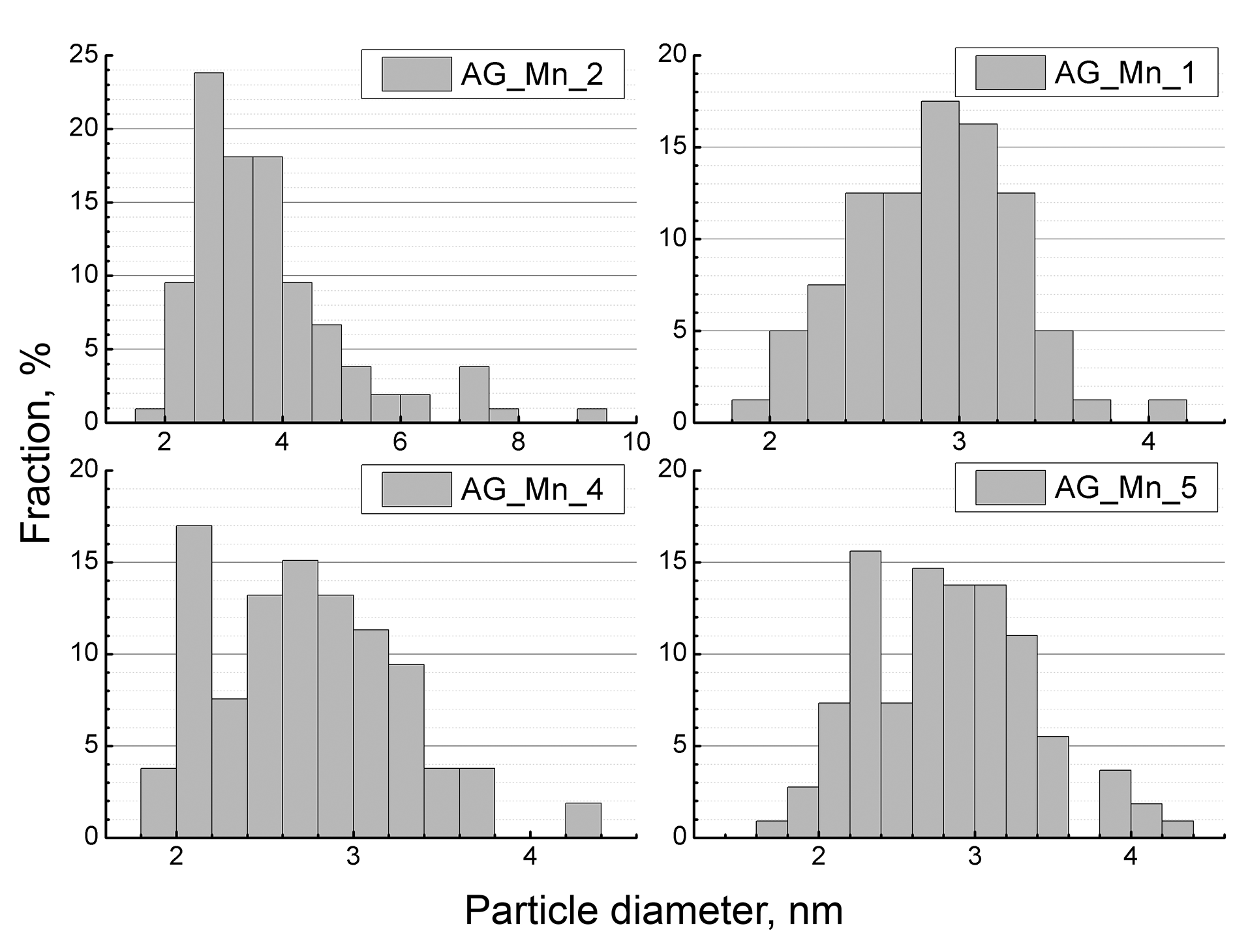

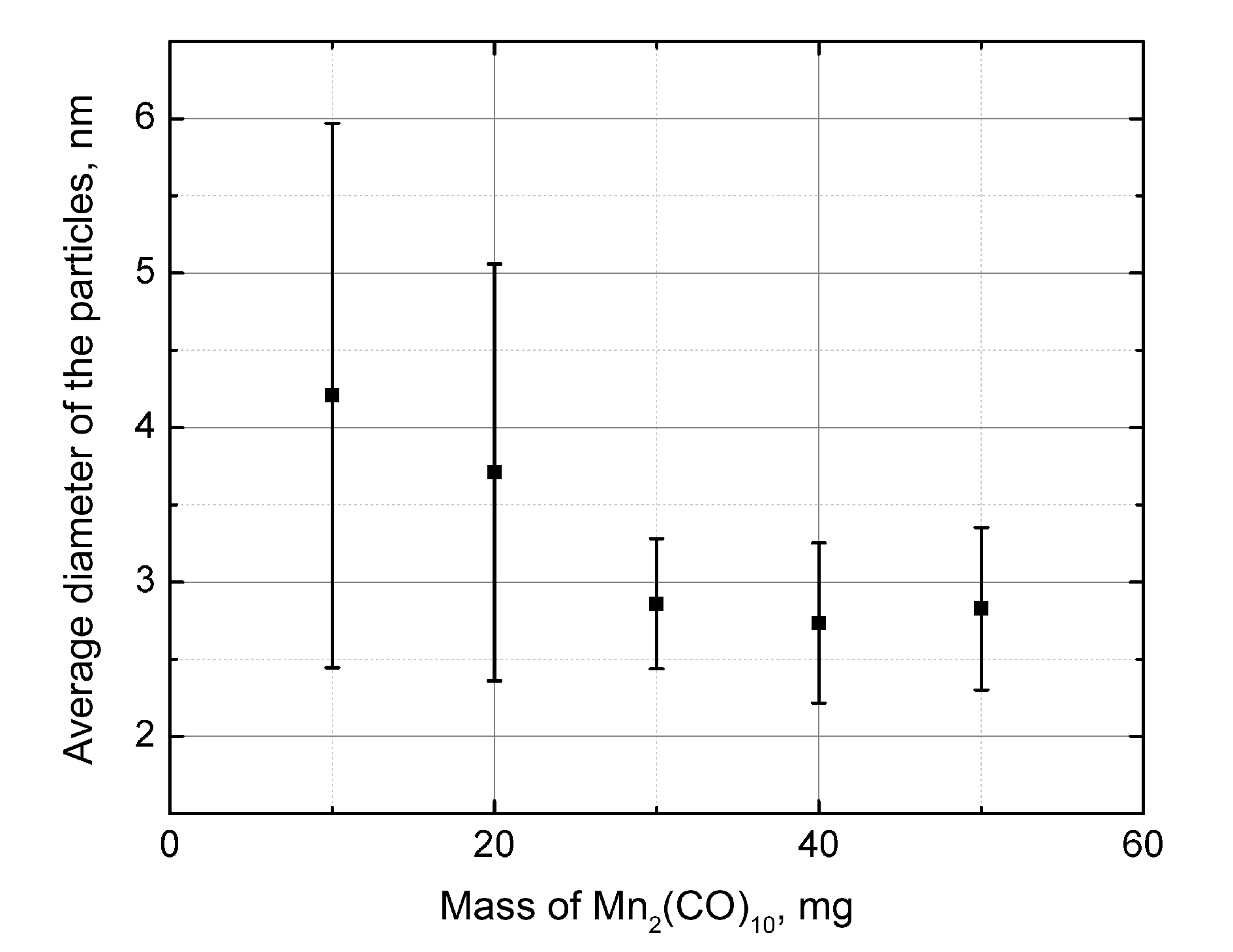

Based on the HRTEM images, the size distribution of the metal-containing particles was determined, and the average and standard deviations were calculated. For each sample, at least 50 particles were measured. As Fig. 5 shows, the composites obtained with the low (30 mg or less) carbonyl loadings are characterized by a unimodal size distribution of the metal oxide particles. For samples AG_Mn_4 and AG_Mn_5, which contain the highest fractions of the metal in the series, the size distribution of the particles is bimodal. The described change in the distribution curve shape may be due to the presence of pores of different sizes in the aerogels. If the concentration of manganese atoms is sufficient, then a significant portion of the smallest pores can be overlapped by the particles during the exposure, which leads to an increase in the peak at ca. 2.2 nm.

Figure 5. Size distributions of the metal oxide particles in the composites obtained upon addition of 20, 30, 40, or 50 mg of Mn2(CO)10.

The dependence of the average diameter of the metal oxide particles on the mass of the added carbonyl is presented in Fig. 6. For all samples, the average diameter values lie in the range of 2.7–4.2 nm, and given the statistical spread, from 2.0 to 6.0 nm. Consequently, the particles are highly dispersed and have a narrow size distribution. A considerable spread of the data does not allow for outlining a clear trend in the variation of the particle sizes depending on the precursor loading. By the order of magnitude, the mentioned diameters coincide with the particle sizes observed in the TEM images in Ref. [27].

Figure 6. Dependence of the average diameter of the metal-containing particles on the mass of the added precursor.

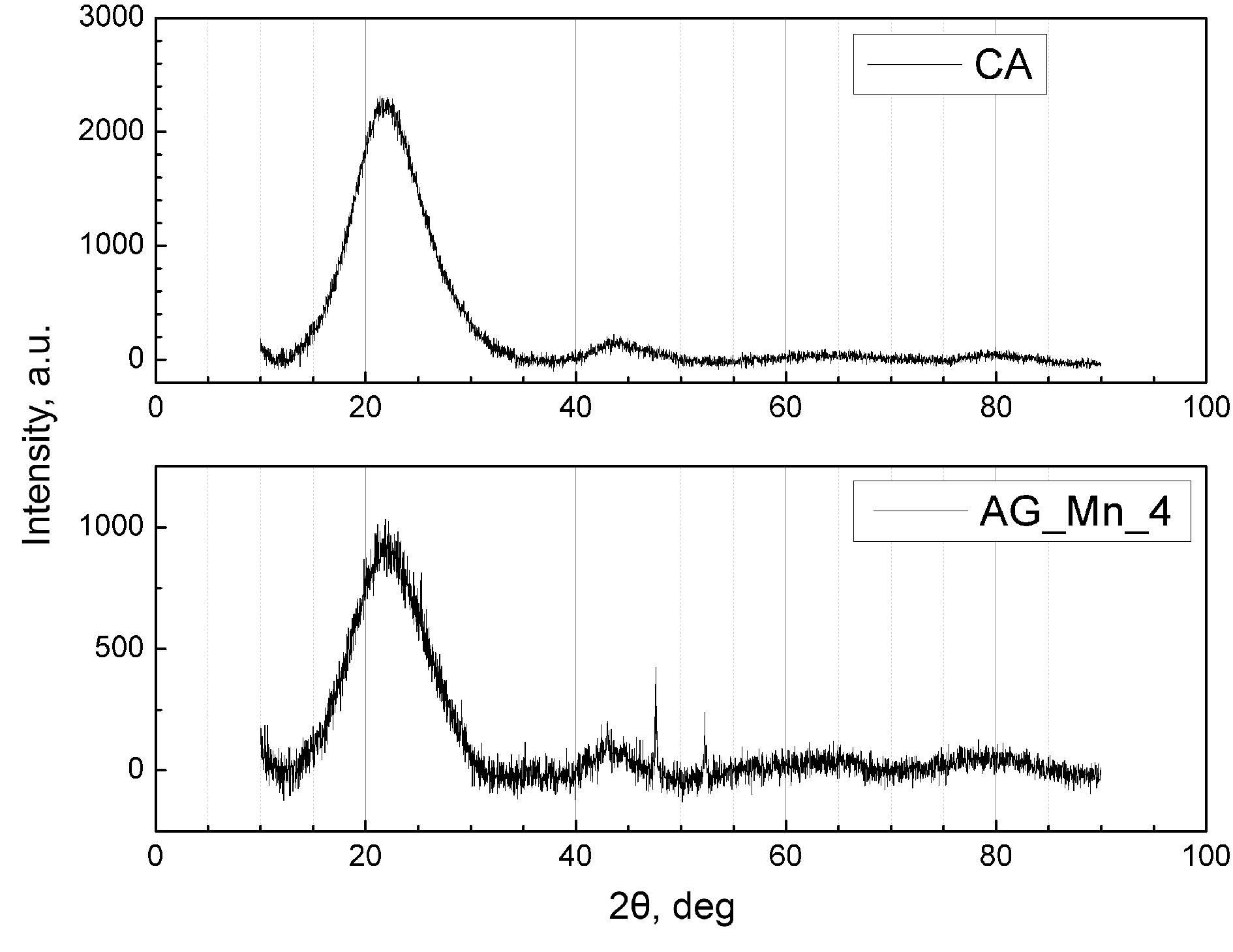

The X-ray patterns of the resulting aerogels contain two broad peaks at about 23° and 44°, which is typical for weakly graphitized carbon monoliths, as was noted earlier [10, 15]. As can be seen from Fig. 7, the X-ray diffraction pattern of sample AG_Mn_4 does not show a pattern corresponding to crystalline manganese oxides; therefore, most of the incorporated metal oxide particles are amorphous (the X-ray diffraction patterns are shown after deduction of a baseline). We failed to establish whether the peaks at ca. 47° and 52° correspond to any compounds of the elements being present in the samples.

Figure 7. X-ray diffraction patterns of the reference aerogel CA and the composite prepared with the addition of 40 mg of the precursor.

The low-temperature nitrogen adsorption/desorption is characterized by type IV isotherms for both the reference sample and the doped carbon aerogels (Fig. 8a), which indicates their mesoporous nature. The experimental nitrogen adsorption isotherms were used to calculate pore surface area as(BET) using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method (Table 3) [38]. Since the carbon aerogels of the same series, taken in the form of monoliths of identical masses and similar shapes, were used as substrates for the deposition of manganese oxide particles, then to assess the effect of the doping procedure on the morphology of aerogels, it seemed reasonable to calculate their total surface area (Table 3). The calculated surface area of the composites decreases compared to the reference sample (by 0.2%) in the case of only one of four composites of the series; therefore, a visible decrease in as(BET) is primarily associated with an increase in the monolith mass and, most likely, is not indicative of a change in the structure or adsorption properties of the carbon matrix. The specific surface area of all the samples obtained is more than 600 m2/g, which determines their high adsorption properties. The values of as(BET) are noticeably higher than the specific surface areas of the composite carbon aerogels with manganese oxides, which were obtained earlier [18, 22]. The method of the composite synthesis described in Ref. [22] did not include the stage of drying in a supercritical fluid, which is conventional for the resorcinol–formaldehyde procedure. Instead, the gels with the incorporated manganese precursor were dried in air at 60 °C, which could lead to narrowing of the pores due to surface tension forces arising at the liquid–gas interface and a loss of a significant part of the area (the best result was 228 m2/g). Li et al. [18], deposited manganese oxides onto the preformed carbon matrix through electrolysis of a manganese precursor. The investigations performed by the authors showed that the oxide coating is distributed over most of the surface of the carbon aerogel, so that the specific surface area is expectedly close (120 m2/g) to the values obtained, for example, for a neat manganese oxide aerogel (69–171 m2/g) [28]. Compared to the previous results [21, 27], the thermo-oxidative decomposition of carbonyls affords the composites, the adsorption capacity of which is insignificantly lower (610–680 m2/g vs. 859 m2/g, 963 m2/g), but, at the same time, implies simple control of the porosity characteristics of the resulting composite.

Figure 8. Isotherms of low-temperature N2 adsorption/desorption at 77.35 K (a), CO2 adsorption/desorption at 273.15 K (b).

Table 3. Specific (BET) and total (calculated) surface areas of the aerogels obtained

|

Sample

|

as(BET), m2/g

|

Surface area (calc.), m2

|

|

CA

|

841

|

42.1

|

|

AG_Mn_2

|

682

|

42.3

|

|

AG_Mn_3

|

670

|

42.0

|

|

AG_Mn_4

|

672

|

45.4

|

|

AG_Mn_5

|

611

|

43.3

|

The CO2 adsorption/desorption isotherms (Fig. 8b) were analyzed using density functional theory (DFT). In addition, the DFT and the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) methods were used to process the N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms. For reference sample CA and four composite aerogels, the specific surface areas and total pore volumes were calculated using the BET, BJH, and DFT methods (see Table S1 in the Electronic supplementary information (ESI)); in addition, their pore size distributions were obtained.

The pore size distributions for the samples with the precursor loadings of 0–40 mg did not differ significantly, which once again confirms the preservation of a three-dimensional structure of the aerogels. No specific mesopore fractions (3–50 nm) were identified in the pore size distributions for the samples explored. All of them were characterized by the presence of small fractions of micropores in the region of 1–2 nm and ultramicropores of 0.4–0.6 nm (Fig. S1 in the ESI).

Experimental section

The synthesis of carbon aerogels was carried out according to the published method [35]. An aqueous solution of formaldehyde (37%, stabilized with methanol, Fisher Chemical, 2.2 mL) was added dropwise to a mixture of resorcinol (Acros Organics, ≥98%, 1.62 g) and catalyst Na2CO3·H2O (Merck, 99.5%, 15 mg) in distilled water. The molar ratios of resorcinol (R), formaldehyde (F), and the catalyst (C) were R/F = 0.5 and R/C = 100. The solution was stirred for at least 1 h, then poured into plastic tubes and placed in a drying oven (FD23, Binder, Germany) for thermostating. The latter was carried out at 70 °C for 48 h. As the synthesis completed, the resulting cylindrical gels were transferred to containers with an excess of acetone (Komponent-Reaktiv, ≥99.75%), after which the solvent was repeatedly replaced with fresh portions of acetone with an exposure time of at least 48 h at each step. The solvent replacement (for supercritical CO2) and supercritical drying were carried out in an experimental setup that included a flow reactor from Waters, USA, a High Pressure Equipment 81-5.75-10 generator (HPG) (USA), and an automatic back pressure regulator from Waters, USA. Upon completion of supercritical drying, the pressure in the reactor was released at a rate of 1–2 bar/min. The carbonization was carried out in a Carbolite HTV 12/80/700 vacuum oven (UK) under high vacuum at 900 °C. The duration of carbonization was 8 h.

The resulting carbon monoliths were divided into 50 mg individual monolithic samples, which were placed in a 3.5 mL high-pressure reactor together with Mn2(CO)10 (98%, Sigma-Aldrich, no. 245267). The carbonyl mass varied from 10 to 50 mg, the corresponding values and notation are given in Table 1. The reactor with the reagents was hermetically sealed and oxygen was pumped in (OOO Germes-Gaz, ≥99.7%) under a pressure of 10 bar at room temperature (23 °C). The experimental parameters were calculated according to the gas state equation using the NIST Chemistry WebBook program software (National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA). Under the chosen conditions, the density of O2 was 0.013255 g/mL, and the amount of O2 was therefore 1.45 mmol. Since, according to the calculations, 1.09 mmol of O2 was required for the complete oxidation of 50 mg of Mn2(CO)10 to CO2 and MnOx oxide with any x ≤ 3.5, the available oxygen amount was sufficient for the complete conversion of the precursor. Then the reactor was placed in a thermostat (ET 15 S, LAUDA-Brinkmann, USA), and CO2 (Moscow Gas Processing Plant, ≥99.995%) was injected using a high-pressure generator at a pressure of 100 bar and a temperature of 45 °C. The sealed reactor was exposed in a drying chamber at 140 °C for 24 h, after which the slow (at least 90 min) decompression was carried out in a thermostat at a temperature of 40 °C.

The morphologies of the composite carbon aerogels were studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), X-ray diffraction (XRD), N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms at 77 K, and CO2 adsorption/desorption isotherms at 273 K. The HRTEM analysis and EDX studies were carried out on a JEOL JEM-2100F microscope (Japan). The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms (NOVA 1200e, Quantachrome Instruments, USA) were studied using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) methods as well as density functional theory (DFT) [38–40]. The micropore characteristics of the aerogels were calculated (NOVAtouch 2LX, Quantachrome Instruments, USA) from the adsorption measurements for CO2 using DFT.

Scanning electron microscopy with EDX spectroscopy were performed on a Prisma E microscope (Thermo Scientific, Czech Republic). Secondary electron images were obtained under high vacuum at an accelerating voltage of 3–5 kV. XRD data were obtained on a Rigaku Smartlab SE diffractometer (Japan) in reflective geometry in a stepwise scanning mode with a step of ∆2θ = 0.05° in the range of 2θ = 10–90°.

To determine the metal content in the composites, their X-ray fluorescence scattering spectra were measured and compared with the standard (Spektroskan maks-GVM, Russia; LiF-200 crystal). The carbon/hydrogen content was determined from chromatographic analysis of the sample combustion products at 950 °C (vario MICRO cube analyzer, Elementar Americas Inc., USA).

Conclusions

To summarize the results presented, the thermo-oxidative decomposition of Mn2(CO)10 was found to enable the formation of nanosized particles of manganese oxides inside the monolithic carbon aerogels. It was shown that the metal content in the composites can be adjusted by changing the mass of the added carbonyl. The composite aerogels with the metal mass fractions in the range of 4.1–15.3% were synthesized. Based on the results of X-ray diffraction and HRTEM analysis, it was determined that manganese oxide particles formed in the carbon aerogels are amorphous, highly dispersed, and characterized by a narrow size distribution. Their average sizes were 2.7–4.2 nm. Despite the nonuniform distribution of the particles on a micrometer scale, the distribution of manganese throughout the volume of the aerogels appears to be macroscopically homogeneous.

The HRTEM studies showed that the morphologies of the resulting samples are close to those previously observed in the carbon aerogels with the same synthesis parameters and, besides the incorporation of the metal oxide particles, do not reveal significant changes after high-temperature exposure together with the carbonyl and its decomposition products. The same conclusion was confirmed by the analysis of the surface areas and pore volumes of the aerogels, as well as the comparison of their pore size distributions calculated from the adsorption measurements with N2 and CO2. The analysis of the nitrogen adsorption isotherms using the BET method revealed that the specific surface areas of all composites are more than 600 m2/g, and their decrease with the increasing carbonyl loading and metal content in the sample is mainly associated with an increase in the mass of the monolith and is not a sign of deterioration in the adsorption properties of the aerogels. In contrast, the presence of a developed system of micro-mesopores with a large surface area in the resulting samples determines good adsorption capacity of the aerogels.

The possibility of further development of the work lies in a more detailed study of the properties of the composites. In particular, taking into account the presence of high surface areas in the synthesized metal-containing aerogels, their use in electrocatalysis seems to be highly promising. On the other hand, since in the experiments performed all carbon aerogels were prepared under the same conditions, it seems to be reasonable to use the suggested method for doping carbon aerogels with other porosity characteristics.

Another direction of further investigations is a more detailed study of the adsorption properties of the composite carbon aerogels, in particular in relation to toxic gases. This will allow us to propose technological methods for removing harmful gaseous waste from industrial production.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 21-13-00143).

The compositions of the resulting composites were studied together with the following researchers of the Laboratory of Microanalysis of INEOS RAS: V. N. Talanova, D. Kh. Kitaeva, and L. V. Gumileva. The authors are grateful to S. V. Maksimov (Faculty of Chemistry, Lomonosov Moscow State University) for the TEM measurements performed using the equipment of the Center for Collective Use "Nanochemistry and Nanomaterials" of the Faculty of Chemistry of Lomonosov Moscow State University and supported by the Development Program of Lomonosov Moscow State University. The authors are also grateful to S. M. Kuzovchikov (Department of Chemistry, Lomonosov Moscow State University) and A. A. Gulin (Semenov Institute of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences).

The characterization of the composite materials was performed with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement no. 075-03-2023-642) using the equipment of the Center for Molecular Composition Studied of INEOS RAS.

Electronic supplementary information

Detailed characteristics of the porosity of the resulting composites. For ESI, see DOI: 10.32931/io2305a

References

- A. Du, B. Zhou, Z. Zhang, J. Shen, Materials, 2013, 6, 941–968. DOI: 10.3390/ma6030941

- M. A. Worsley, J. H. Satcher, Jr., T. F. Baumann, Langmuir, 2008, 24, 9763–9766. DOI: 10.1021/la8011684

- M. A. Worsley, P. J. Pauzauskie, S. O. Kucheyev, J. M. Zaug, A. V. Hamza, J. H. Satcher, Jr., T. F. Baumann, Acta Mater., 2009, 57, 5131–5136. DOI: 10.1016/j.actamat.2009.07.012

- R. W. Pekala, J. Mater. Sci., 1989, 24, 3221–3227. DOI: 10.1007/BF01139044

- J. D. Lemay, T. M. Tillotson, L. W. Hrubesh, R. W. Pekala, MRS Online Proc. Libr., 1990, 180, 321. DOI: 10.1557/PROC-180-321

- R. W. Pekala, C. T. Alviso, J. D. LeMay, J. Non. Cryst. Solids, 1990, 125, 67–75. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3093(90)90324-F

- H. D. Asfaw, A. Kucernak, E. S. Greenhalgh, M. S. P. Shaffer, Compos. Sci. Technol., 2023, 238, 110042. DOI: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.110042

- M. Samancı, E. Daş, A. B. Yurtcan, Int. J. Energy Res., 2021, 45, 1729–1747. DOI: 10.1002/er.5841

- F. Li, L. Xie, G. Sun, Q. Kong, F. Su, Y. Cao, J. Wei, A. Ahmad, X. Guo, C.-M. Chen, Microporous Mesoporous Mater., 2019, 279, 293–315. DOI: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.12.007

- D. Jayne, Y. Zhang, S. Haji, C. Erkey, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 2005, 30, 1287–1293. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2005.03.014

- A. N. Malkova, N. A. Sipyagina, I. O. Gozhikova, Y. A. Dobrovolsky, D. V. Konev, A. E. Baranchikov, O. S. Ivanova, A. E. Ukshe, S. A. Lermontov, Molecules, 2019, 24, 3847. DOI: 10.3390/molecules24213847

- H. Kabbour, T. F. Baumann, J. H. Satcher, A. Saulnier, C. C. Ahn, Chem. Mater., 2006, 18, 6085–6087. DOI: 10.1021/cm062329a

- J. Li, X. Wang, Q. Huang, S. Gamboa, P. J. Sebastian, J. Power Sources, 2006, 158, 784–788. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2005.09.045

- J. Shen, W. Han, Y. Mi, Y. On, G. Wu, B. Zhou, Z. Zhang, X. Ni, X. Niu, G. Wang, P. Wang, Q. Wang, in: 2008 2nd IEEE Int. Nanoelectron. Conf. INEC 2008, IEEE 2008, pp. 74–77. DOI: 10.1109/INEC.2008.4585440

- Y. J. Lee, H. W. Park, S. Park, I. K. Song, Curr. Appl. Phys., 2012, 12, 233–237. DOI: 10.1016/j.cap.2011.06.010

- Y. J. Lee, H. W. Park, U. G. Hong, I. K. Song, Curr. Appl. Phys., 2012, 12, 1074–1080. DOI: 10.1016/j.cap.2012.01.009

- Y. J. Lee, J. C. Jung, S. Park, J. G. Seo, S.-H. Baeck, J. R. Yoon, J. Yi, I. K. Song, Curr. Appl. Phys., 2011, 11, 1–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.cap.2010.06.001

- G.-R. Li, Z.-P. Feng, Y.-N. Ou, D. Wu, R. Fu, Y.-X. Tong, Langmuir, 2010, 26, 2209–2213. DOI: 10.1021/la903947c

- Y.-H. Lin, T.-Y. Wei, H.-C. Chien, S.-Y. Lu, Adv. Energy Mater., 2011, 1, 901–907. DOI: 10.1002/aenm.201100256

- X. Wang, L. Liu, X. Wang, L. Yi, C. Hu, X. Zhang, Mater. Sci. Eng. B, 2011, 176, 1232–1238. DOI: 10.1016/j.mseb.2011.07.003

- Y. Xu, S. Wang, B. Ren, J. Zhao, L. Zhang, X. Dong, Z. Liu, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2019, 537, 486–495. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.11.023

- Q. Meng, L. Du, J. Yang, Y. Tang, Z. Han, K. Zhao, G. Zhang, Colloids Surf., A, 2018, 548, 142–149. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.03.064

- M. Sánchez-Polo, J. Rivera-Utrilla, U. von Gunten, Water Res., 2006, 40, 3375–3384. DOI: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.07.020

- F. J. Maldonado-Hódar, M. A. Ferro-Garcı́a, J. Rivera-Utrilla, C. Moreno-Castilla, Carbon, 1999, 37, 1199–1205. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6223(98)00314-5

- T. F. Baumann, G. A. Fox, J. H. Satcher, N. Yoshizawa, R. Fu, M. S. Dresselhaus, Langmuir, 2002, 18, 7073–7076. DOI: 10.1021/la0259003

- C. D. Saquing, T.-T. Cheng, M. Aindow, C. Erkey, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2004, 108, 7716–7722. DOI: 10.1021/jp049535v

- K. Wang, Q. Meng, L. Du, Y. Tang, K. Zhao, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2021, 23, 27. DOI: 10.1007/s11051-020-05112-1

- V. V Zefirov, I. V Elmanovich, A. V Pastukhov, E. P. Kharitonova, A. A. Korlyukov, M. O. Gallyamov, J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol., 2019, 92, 116–123. DOI: 10.1007/s10971-019-05092-2

- I. V Elmanovich, V. V Zefirov, I. D. Glotov, V. E. Sizov, E. P. Kharitonova, A. A. Korlyukov, A. V Pastukhov, M. O. Gallyamov, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2021, 23, 95. DOI: 10.1007/s11051-021-05138-z

- I. V. Elmanovich, V. V. Zefirov, INEOS OPEN, 2021, 4, 112–116. DOI: 10.32931/io2115a

- F.-M. Kong, J. D. LeMay, S. S. Hulsey, C. T. Alviso, R. W. Pekala, J. Mater. Res., 1993, 8, 3100–3105. DOI: 10.1557/JMR.1993.3100

- M. Mirzaeian, Q. Abbas, D. Gibson, M. Mazur, Energy, 2019, 173, 809–819. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.02.108

- Q. Abbas, M. Mirzaeian, A. A. Ogwu, M. Mazur, D. Gibson, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 2020, 45, 13586–13595. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.04.099

- T. Bordjiba, M. Mohamedi, L. H. Dao, Adv. Mater., 2008, 20, 815–819. DOI: 10.1002/adma.200701498

- I. V. Elmanovich, M. S. Rubina, S. S. Abramchuk, Dokl. Phys. Chem., 2020, 493, 123–126. DOI: 10.1134/S0012501620080011

- J. M. Miller, B. Dunn, Langmuir, 1999, 15, 799–806. DOI: 10.1021/la980799g

- S. Wang, Y. Xu, M. Yan, Z. Zhai, B. Ren, L. Zhang, Z. Liu, J. Electroanal. Chem., 2018, 809, 111–116. DOI: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.12.045

- M. Eddaoudi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 127, 14117. DOI: 10.1021/ja041016i

- M. Thommes, K. Kaneko, A. V. Neimark, J. P. Olivier, F. Rodriguez-Reinoso, J. Rouquerol, K. S. W. Sing, Pure Appl. Chem., 2015, 87, 1051–1069. DOI: 10.1515/pac-2014-1117

- P. I. Ravikovitch, A. Vishnyakov, R. Russo, A. V. Neimark, Langmuir, 2000, 16, 2311–2320. DOI: 10.1021/la991011c