2023 Volume 6 Issue 3 (Published 30 June 2024)

|

INEOS OPEN, 2023, 6 (3), 91–96 Journal of Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds Download PDF |

|

Synthesis and Properties of Organic–Inorganic Materials

Based on Polyurethane and MQ Resins

D. A. Khanin, G. G. Nikiforova, and O. A. Serenko

Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Vavilova 28, str. 1, Moscow, 119334 Russia

Corresponding author: E. S. Afanasyev, e-mail:nambrot@yandex.ru

Received 7 November 2023; accepted 19 December 2023

Abstract

Cross-linked polyurethanes (PUs) were obtained by curing with MQ resins bearing oxymethyldimethylsiloxane or oxyethoxymethyldimethylsiloxane groups, their mixtures with 1,4-butanediol, and neat 1,4-butanediol and studied for their physico-mechanical properties. The MQ resins with functional hydroxy groups were found to act as polyols during curing of a urethane prepolymer. The network PU, obtained by curing with the MQ resins, represents a hybrid organic–inorganic polymer with bulk cross-links of inorganic nature, the surface groups of which are chemically bound to the polymer matrix. At a concentration of the MQ resins of 0.5 ppm, the properties of hybrid polyurethanes are comparable to those of the polyurethane obtained using 0.63 ppm of 1,4-butanediol.

Key words: polyurethane, prepolymer, MQ resin, physico-mechanical properties.

Introduction

Polyurethanes are used in many fields of industry, including construction, automobile manufacturing, electronics, biomedicine, etc. A wide variety of starting monomers ensures the creation of compositions with target properties and their tuning within very wide limits [1]. The introduction of various fillers, in particular, nanoscale ones, allows for improving the operational characteristics of polyurethane composites (thermal stability, strength, etc.) [2–5].

When producing polymer nanocomposites, researchers face the problem of uniform distribution of nanoparticles in the matrix to achieve the required operational characteristics of the resulting materials. To avoid aggregation of nanoparticles, their surface is often treated with finishing agents, for example, organosilanes, which improve their compatibility with a polyurethane matrix [6]. In other cases, nanoscale inorganic blocks are incorporated into the polymer chain during the polyurethane synthesis [7–9].

MQ oligomers (or MQ resins) represent hybrid organic–inorganic materials featuring nano-sized cross-linked inorganic regions limited by triorganosilyl groups and with a certain number of mobile linear units. These resins can be considered as composites consisting of separate parts that play the roles of a polymer matrix, a plasticizer and a nano-sized filler [10, 11], which can be used as a "supplier" of nano-sized particles when mixed with another polymer [12].

The introduction of functional groups into MQ resins can expand their application scope owing to the emergence of new properties of the resins themselves and the possibility of using them as intermediates for further transformations in compositions based on organic polymers [13]. Meshkov et al. studied PDMS/MQ resin compositions [14] and assumed that MQ resins, having dual properties (macromolecules and nanoscale particles), act as homogeneous binders and active fillers, significantly improving mechanical properties of the cured PDMS rubber. It is important that the residual hydroxy groups of the MQ resin are able to react with the terminal ethoxy groups of the rubber.

Taking into account the above mentioned, the MQ resins bearing hydroxy functional groups can be considered as potential cross-linking agents in the production of cross-linked polyurethanes. During the synthesis of these polymers, they will probably be able not only to form bulky cross-link moieties, but also to act as a filler, the surface groups of which will be able to chemically bind with the polymeric matrix. Consequently, the use of an MQ oligomer with hydroxy groups in a urethane polymer will enable the production of a hybrid organic–inorganic network polymer, in which one part of the network cross-links is nanoscale inorganic blocks [SiO2], and the other one is a fragment of an organic branched polyester.

The purpose of this work was to determine the conditions for obtaining cross-linked compositions based on polyurethane and MQ oligomer, in which the network cross-links would feature significantly different structure, and to study the properties of the resulting hybrid cross-linked polyurethanes.

Results and discussion

In this work, polyurethanes obtained using only 1,4-butanediol (BDO) are considered as the reference samples and the effect of the MQ resins on the properties of the resulting systems is evaluated relative to these polyurethanes.

At the first stage, we explored the principal possibility of the involvement of OH groups of the hydroxy-substituted MQ resins in the curing of a urethane prepolymer by partially replacing the conventional curing agent (BDO) for the MQ resin. The total content of OH groups in the mixture BDO–MQ resin with oxymethyldimethylsiloxane groups (MQ1) or BDO–MQ resin with oxyethoxymethyldimethylsiloxane groups (MQ2) only slightly differed from that in the calculated sample of BDO (see the Experimental section, formula (1)). Thus, the [OH]BDO–MQ1/[OH]BDO and [OH]BDO–MQ2/[OH]BDO ratios were 0.946 and 0.952, respectively. Table 1 presents the properties of the cured PU samples. When using the BDO–MQ1 and BDO–MQ2 mixtures, the content of the gel fraction in the cured urethane prepolymer reduced by 3 and 7%, respectively, compared to the reference sample (PU–BDO). The samples cured with the BDO–MQ resin mixture have a lower density than the reference one, while the use of the BDO–MQ2 mixture facilitates the production of a less dense network polymer than in the case of the BDO–MQ1 (Table 1).

Table 1. Physico-mechanical properties of the cured PUs

|

Curing agent, ppm

|

Gel fraction

yield, % |

r,

g/cm3 |

σр,

MPa |

εrel,

% |

Е,

MPa |

Мс, *103, g/mol

|

Тg, °С

|

Тd, °C

(TMA)

|

Td5%, °C

(TGA)

|

||

|

BDO

|

MQ1

|

MQ2

|

|||||||||

|

0.63

|

0

|

0

|

96

|

1.209

|

1.05 ± 0.18

|

157 ± 46.29

|

1.48 ± 0.12

|

6.18

|

–36

|

256

|

250

|

|

0.26

|

0.45

|

0

|

93

|

1.171

|

1.04 ± 0.03

|

121 ± 2.37

|

1.78 ± 0.04

|

4.90

|

–37

|

205

|

270

|

|

0.26

|

0

|

0.45

|

89

|

1.159

|

0.81 ± 0.05

|

175 ± 14.10

|

0.99 ± 0.04

|

8.67

|

–35

|

192

|

258

|

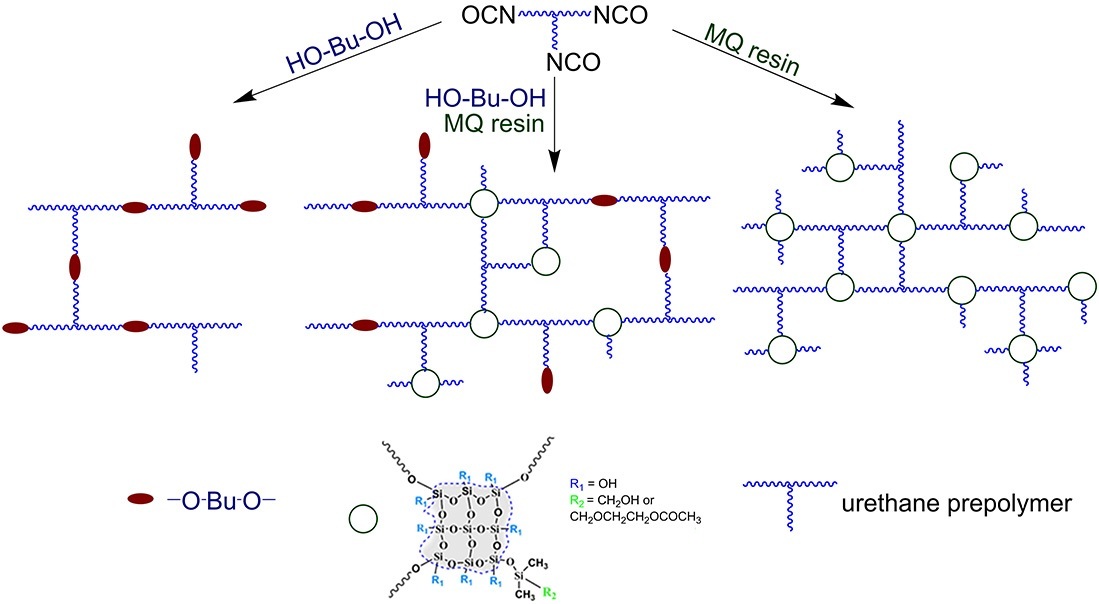

Figure 1 shows the thermomechanical curves of the samples explored. Table 1 lists their glass transition temperatures (Tg) and thermal decomposition temperatures (Td). While the BDO–MQ-resin curing agents do not affect the glass transition temperature of the polymer, its temperature of thermooxidative destruction decreases and is lower than the corresponding value for the PU–BDO sample. The negative impact of MQ2 on thermal stability of the resulting compositions is more pronounced than in the case of MQ1.

Figure 1. Thermomechanical curves of the PU samples cured with BDO (1), BDO–MQ1 (2) and BDO–MQ2 (3) mixtures.

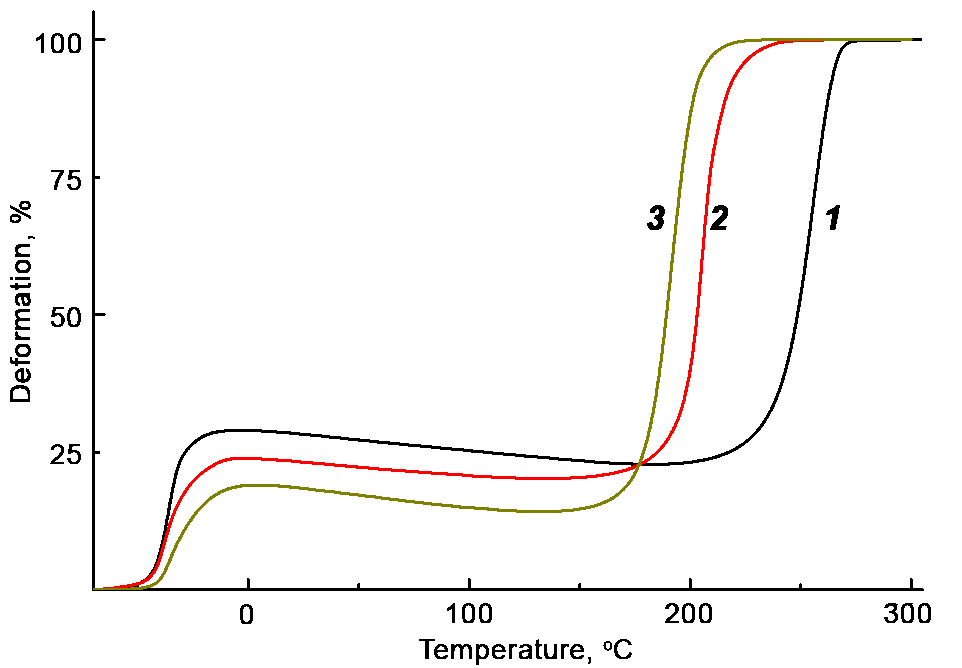

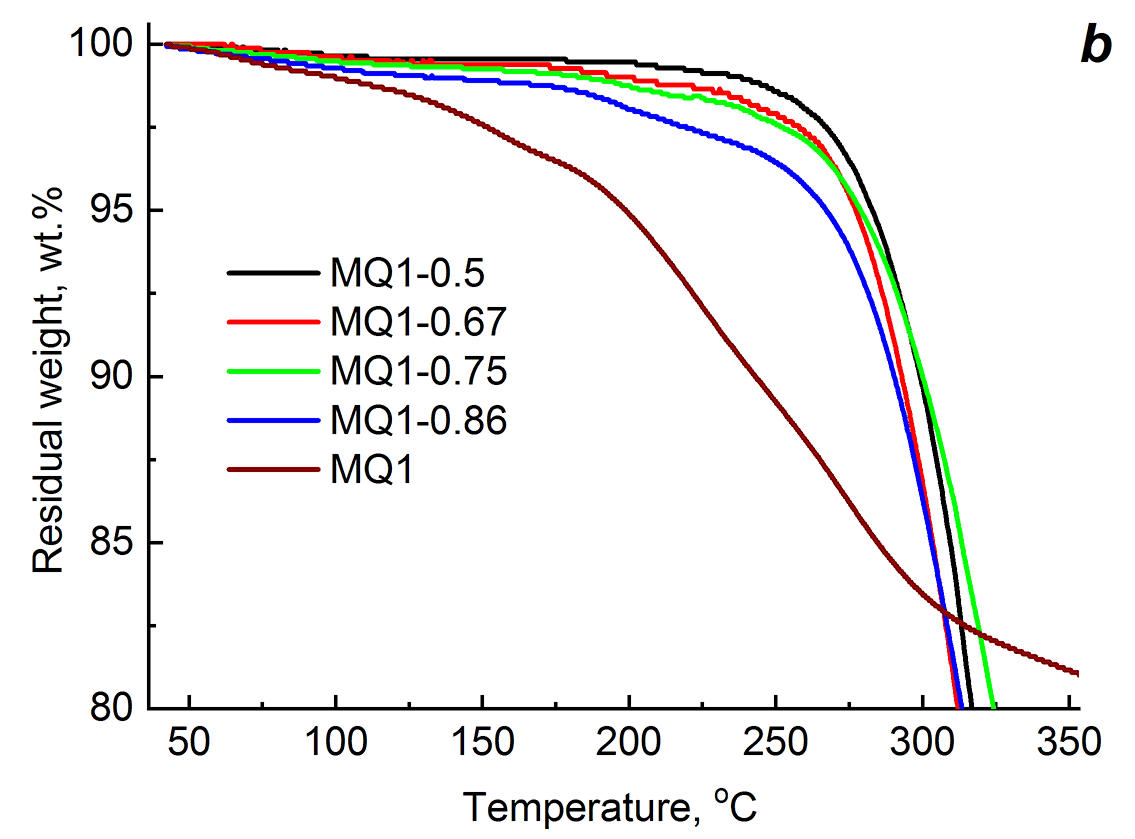

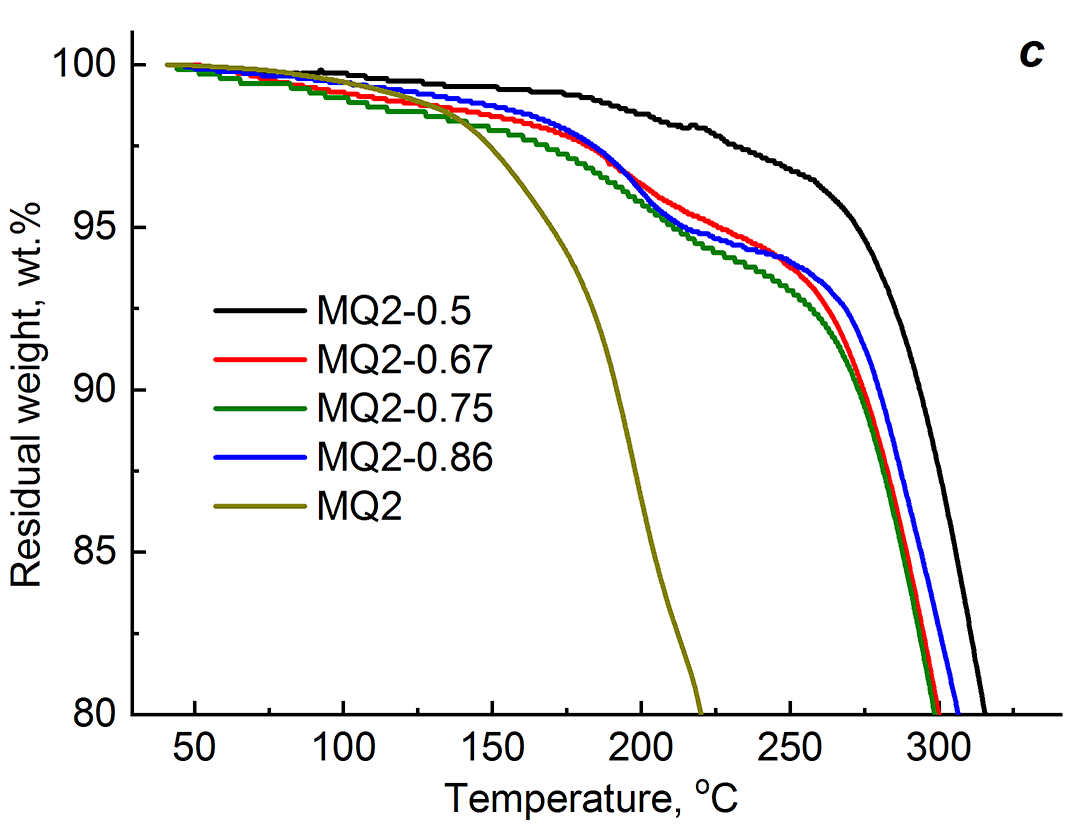

The reason for a decrease in the thermal stability of the PU–BDO–MQ resin compositions lies in the thermal stability of the initial MQ resins. Figure 2 shows initial sections of the thermogravimetric curves of the polyurethane samples cured with BDO and the BDO–MQ resin mixtures, as well as the thermogravimetric curves of starting MQ1 and MQ2. The TGA curves over the whole temperature range are depicted in Fig. S1 in the Electronic supplementary information (ESI). The thermooxidative decomposition of the MQ resins starts at a lower temperature than in the case of PU–BDO. Thus, the temperature of the onset of rapid mass loss (T0) for PU–BDO is 210 °C, while in the case of MQ1 and MQ2 it is lower and equal to 185 and 140 °C, respectively. In the temperature range of 140–250 °C, i.e., prior to the intensive decomposition of the samples cured with a mixture of curing agents, their masses decrease with a temperature rise. BDO–MQ2 curing agent leads to a greater mass loss than BDO–MQ1. Obviously, the loss of the sample mass in this temperature range is due to thermal oxidation processes of the MQ resins included in the two-component curing agent. Despite this, as can be seen from Fig. 2, the decomposition rate of PU–BDO–MQ resin is less than that of PU–BDO. This circumstance is indicated by the values of T5%, which for PU–BDO–MQ1 are higher than for PU–BDO-MQ2. In turn, T5% for PU–BDO–MQ2 is higher than that for PU–BDO (Table 1). Consequently, a decrease in the thermal stability of the compositions cured with BDO–MQ-resin, which was revealed during the thermomechanical studies, is caused by the low thermal stability of the MQ resin used as the second component of the mixed curing agent.

Figure 2. Thermogravimetric curves of the PUs obtained using different curing agents: BDO and mixtures BDO–MQ1, BDO–MQ2 (a);

MQ1 (b) and MQ2 (c) at different resin concentrations.

Table 1 shows the mechanical characteristics of the cured samples. The elastic modulus of PU–BDO–MQ1 is 1.2 times higher than that of PU–BDO, while the strength and elongation at break values are similar. The strength characteristics of PU–BDO–MQ2 are lower and the relative elongation at break is greater than those for PU–BDO. Taking into account that the content of the gel fraction in PU–BDO–MQ2 is less than in the other two compositions explored, a decrease in its strength properties can be associated with a more sparse network (Mc = 8.67·103 g/mol). However, a 1.5-fold decrease in the elastic modulus in the case of the PU–BDO-MQ2 composition compared to the PU–BDO system indicates the existence of an additional reason for its decrease.

Based on the results of the performed investigations, it can be concluded that the MQ resins mixed with BDO not only do not interfere with the curing processes of the urethane prepolymer, but also participate in them on a par with BDO. In other words, the OH functional groups of both MQ1 and MQ2 are active and interact with the isocyanurate groups of the urethane prepolymer, just like hydroxy groups of BDO. Due to the low thermooxidative stability of the MQ resins used in this work, the thermooxidative stability of the polymers cured with a mixture of curing agents decreases.

At the second stage, the urethane prepolymer was cured using only the MQ resins. The contents of MQ1 and MQ2 varied over a wide range, namely, from a clear lack of OH groups in the reaction mixture to their excess relative to [OH]BDO (Table 2). As the content of MQ1 or MQ2 increases, the content of the gel fraction decreases, and the degree of swelling in acetone increases. The difference between the PU–MQ1 and PU–MQ2 compositions is observed in the variation of the sample density (ρ) as the curing agent content increases. Thus, when using MQ1, the value of ρ increases as the concentration of this curing agent increases to 0.75 ppm (from 1.091 to 1.131 g/cm3), and at the content of 0.86 ppm, it slightly decreases. In the case of MQ2, the highest value of ρ among the samples was obtained at the MQ2 content of 0.5 ppm. At the higher MQ2 content, the density of the samples appeared to be less than the mentioned one. The concentration and type of the MQ resins do not affect the glass transition temperature of the compositions. No significant decrease was observed in the thermal stability of the cross-linked PU–MQ1 samples containing up to 0.75 ppm of the curing agent (a decrease by 2 deg). For the composition with 0.86 ppm of MQ1, the value of Td decreased by 5 deg. In the case of PU–MQ2, this temperature increased with increasing concentration of MQ2, and for PU–0.86 ppm of MQ2 the difference with the corresponding temperature for PU–0.50 ppm of MQ2 composed 7 deg. However, the temperature characterizing the thermooxidative stability of the compositions (T5%) decreased for both PU–MQ1 and PU–MQ2, which is likely to be due to an increase in the content of the component that is less thermally stable than the polymer matrix (see above). Figure 2 shows the initial sections of thermogravimetric curves of the resulting compositions (for the full version, see Fig. S1 in the ESI). It is obvious that an increase in the content of the MQ resins lead to the beginning of the mass loss by the samples at a lower temperature.

Table 2. Physico-mechanical properties of the PU samples cured by the MQ resins

|

MQ type

|

MQ concentration, ppm

|

[ОН]MQ

[ОН]BDO

|

Gel fraction

yield, % |

r,

g/cm3 |

Q,

% |

σр,

MPa |

εrel,

% |

Е,

MPa |

Тg, °С

|

Тd, °C

(TMA)

|

Td5%, °C

(TGA)

|

|

MQ1

|

0.50

|

0.267

|

98

|

1.091

|

119

|

1.83 ± 0.09

|

136 ± 9.96

|

2.50 ± 0.05

|

–36

|

201

|

282

|

|

0.67

|

0.563

|

97

|

1.114

|

132

|

1.40 ± 0.08

|

84 ± 5.95

|

2.94 ± 0.05

|

–39

|

199

|

277

|

|

|

0.75

|

0.844

|

96

|

1.131

|

149

|

1.15 ± 0.04

|

61 ± 1.58

|

3.20 ± 0.14

|

–37

|

199

|

277

|

|

|

0.86

|

1.689

|

94

|

1.127

|

182

|

0.93 ± 0.08

|

47 ± 5.19

|

3.20 ± 0.14

|

–36

|

196

|

267

|

|

|

MQ2

|

0.50

|

0.273

|

95

|

1.207

|

124

|

1.88 ± 0.02

|

157 ± 7.08

|

2.43 ± 0.05

|

–34

|

194

|

272

|

|

0.67

|

0.602

|

93

|

1.148

|

168

|

1.08 ± 0.04

|

120 ± 7.55

|

1.70 ± 0.02

|

–37

|

198

|

226

|

|

|

0.75

|

0.904

|

91

|

1.164

|

170

|

0.98 ± 0.02

|

121 ± 3.76

|

1.82 ± 0.02

|

–37

|

198

|

210

|

|

|

0.86

|

1.807

|

89

|

1.166

|

175

|

0.64 ± 0.09

|

75 ± 12.87

|

1.50 ± 0.02

|

–35

|

201

|

210

|

The strength and elongation at break of the samples obtained using MQ1 or MQ2 decreased as the curing agent content increased. Of note is an unusual change in the elastic modulus of these compositions. In the case of PU–MQ1, the elastic modulus increased from 2.5 to 3.2 MPa with increasing MQ1 content, while for PU–MQ2, on the contrary, it decreased.

An increase in the density of the composition and an increase in its degree of swelling in acetone, a decrease in the gel fraction and an increase in the elastic modulus are, at first glance, opposite results. However, they indicate the formation of free MQ1 resin in the composition, i.e., a part of the used resin and a part of its OH groups did not react with the isocyanate groups of the prepolymer. Probably, in the PU–MQ1 system, an increase in the MQ resin content leads to microphase separation, resulting in the formation of resin aggregates (or associates), the elastic modulus of which is higher than that of the polymer matrix. The proposed assumption is based on the fact that, in the initial state, MQ1 is a solid powder. A similar process is observed for the PU–MQ2 system. However, in this case, MQ2 in the initial state is a viscous liquid. As a consequence, a decrease in the density and modulus of the composition can be associated with the fact that the elastic modulus of MQ2 associates is less than that of the surrounding polymer and they act as a plasticizer.

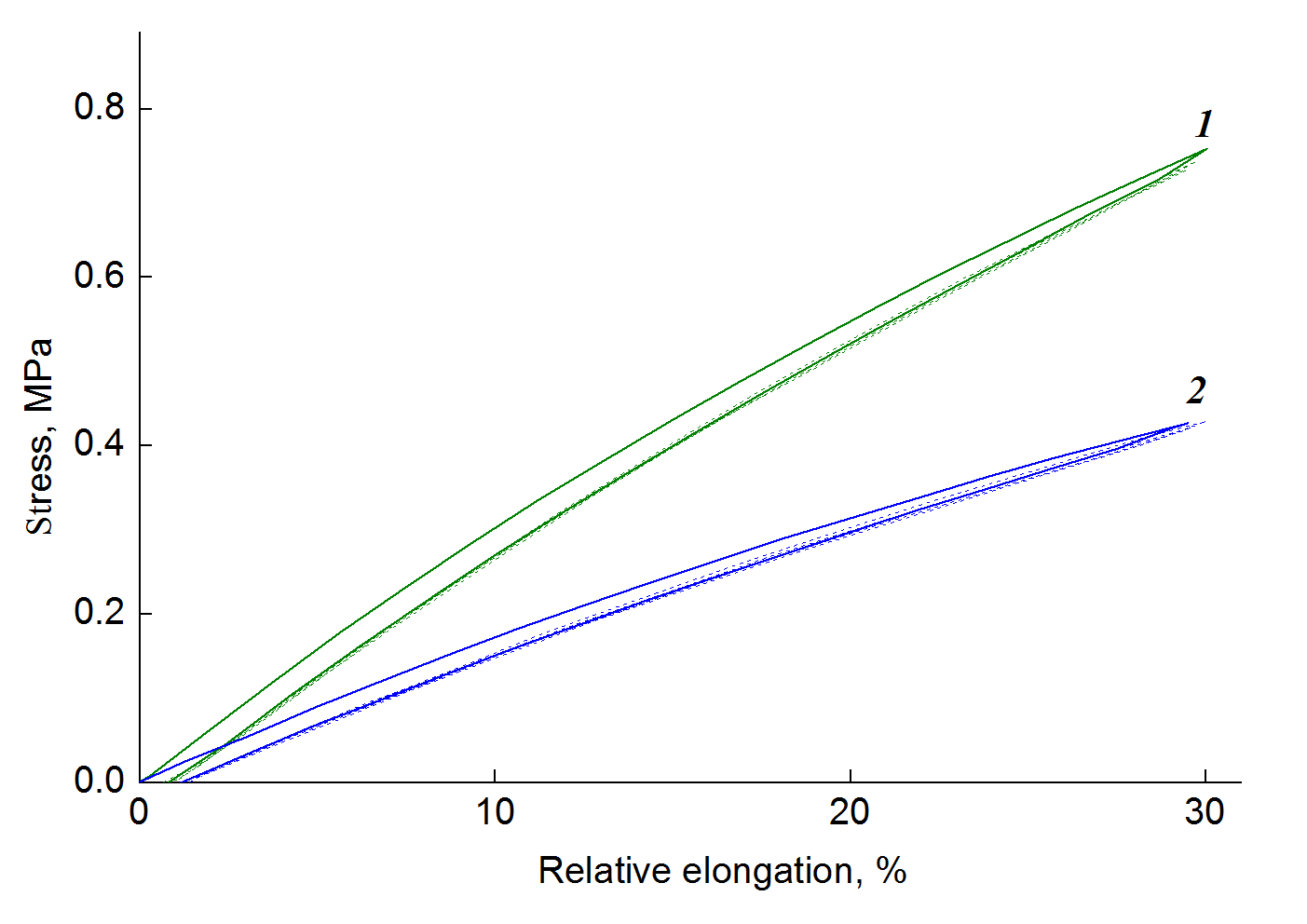

Figure 3 shows the stress–strain curves of the compositions PU–0.67 ppm of MQ1 and PU–0.67 ppm of MQ2 under cyclic exposure to tensile loads. The tensile strain was 30%. While at the first cycle the mechanical hysteresis is minimal, during the second and third cycles, the deformation curves coincide, i.e., starting from the second cycle, the mechanical hysteresis is not visible in the samples. Table 3 presents the strength and elastic modulus of the samples during cyclic tests. The changes in the resulting values are minimal. It can be concluded that the network formed during curing of the urethane prepolymer with MQ resins consists of covalent bonds. The contribution of a physical network to the strength properties of the composites is insignificant.

Figure 3. Stress–strain curves of the PU samples cured with MQ1 (1) or MQ2 resin (2) under cyclic tensile loads.

The content of MQ1 or MQ2 was 0.67 ppm.

Table 3. Strength and elastic modulus of the MQ-cured samples during cyclic tests. The MQ resin concentration was 0.67 ppm

|

Curing agent

|

1st cycle

|

2nd cycle

|

3rd cycle

|

||||

|

σ, MPa

|

Е, MPa

|

S

|

σ, MPa

|

Е, MPa

|

σ, MPa

|

Е, MPa

|

|

|

MQ1

|

0.75

|

3.0

|

1.2·10–2

|

0.74

|

2.85

|

0.73

|

2.88

|

|

MQ2

|

0.43

|

1.71

|

1.8·10–2

|

0.43

|

1.64

|

0.42

|

1.65

|

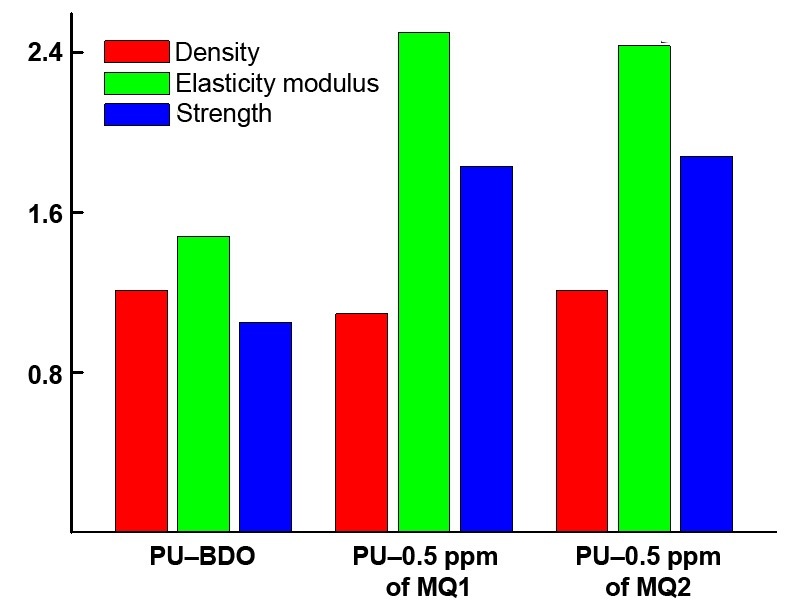

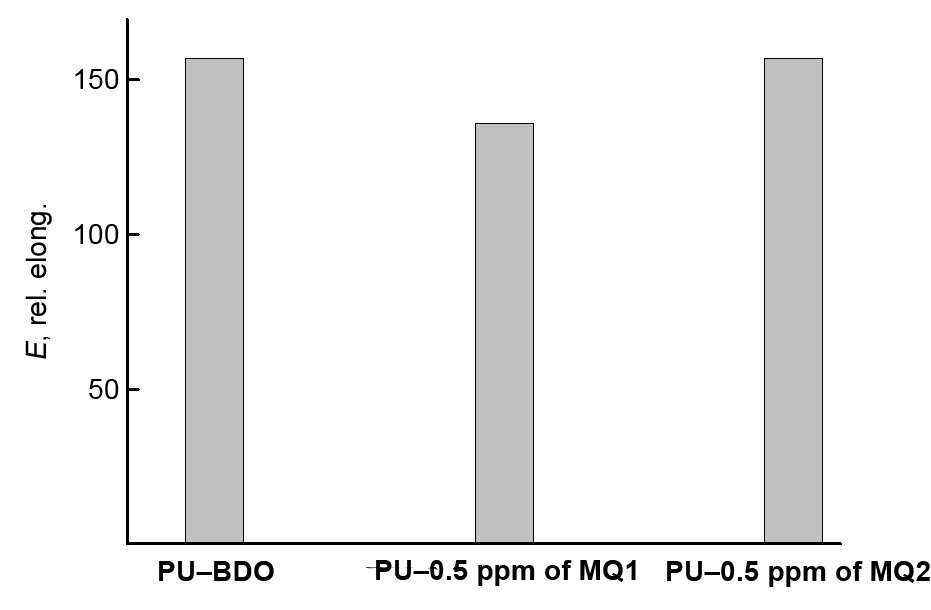

The concentration of MQ1 or MQ2 used as the urethane prepolymer curing agents equal to 0.5 ppm can be considered as the optimal one. Figure 4 compares the densities and stress–strain characteristics of the samples of these compositions with those of the reference (PU–BDO). At these resin contents, they are not inferior to the reference sample.

Figure 4. Histograms comparing the characteristics of the cured PUs: density, modulus of elasticity, tensile strength (a) and elongation at break (b).

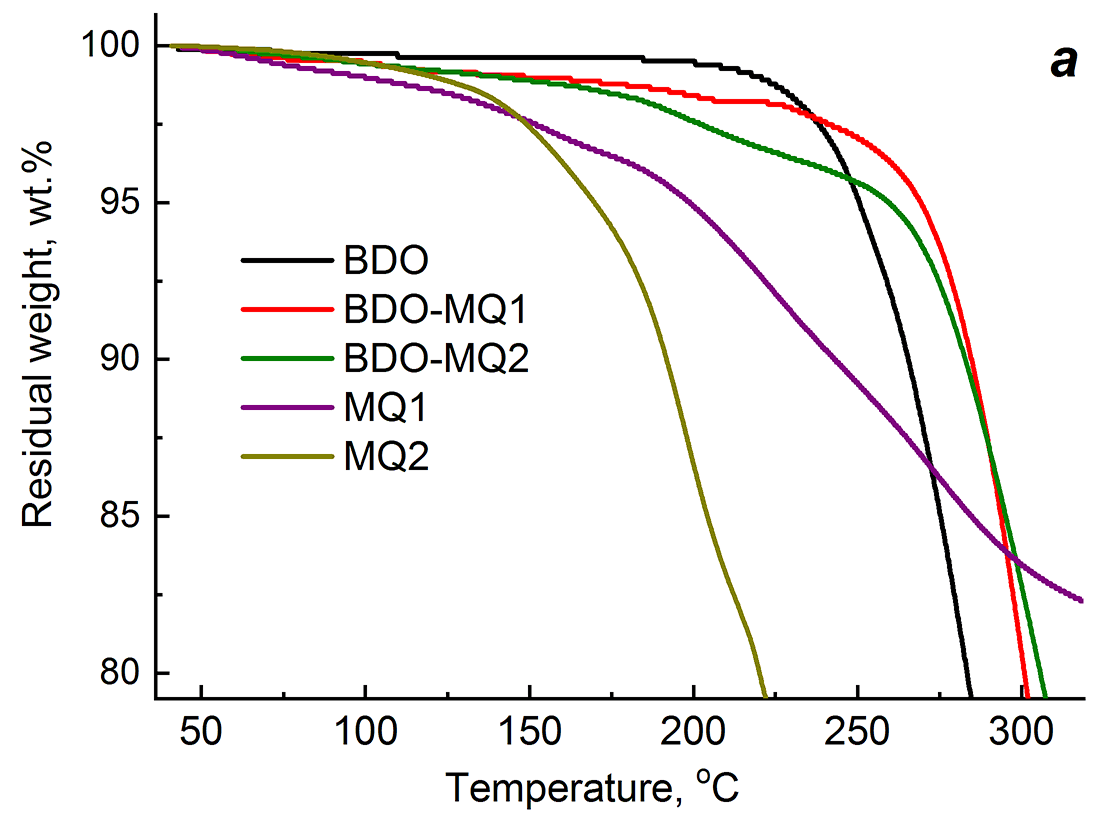

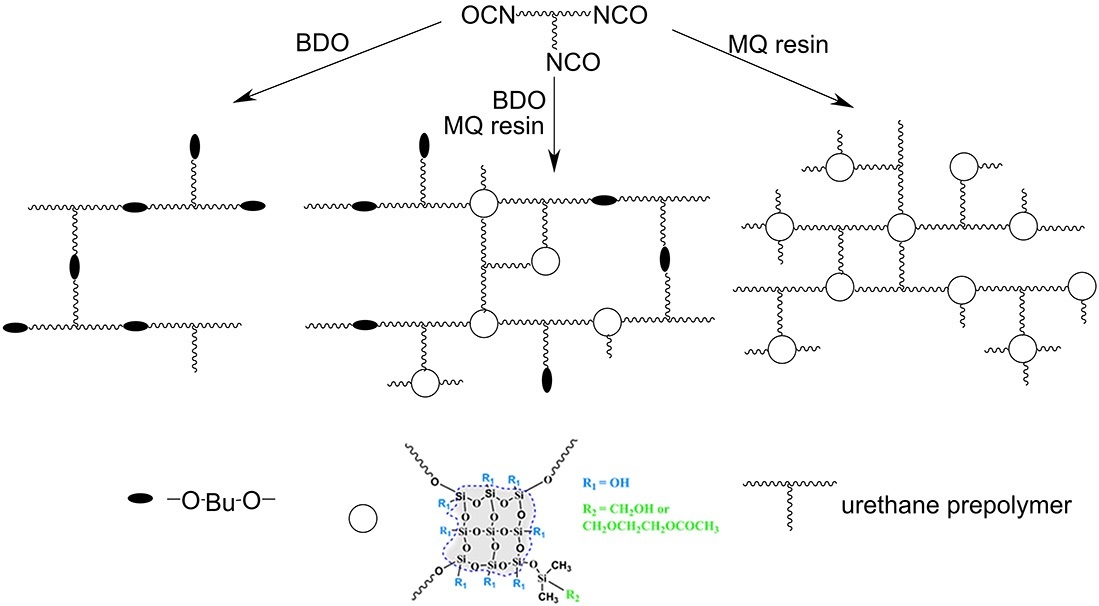

Based on the results obtained, it can be stated that the use of the MQ resins with an oxymethyldimethylsiloxane (MQ1) or oxyethoxymethyldimethylsiloxane (MQ2) framework as the curing agents (polyols) for a urethane prepolymer enables the production of a hybrid organic–inorganic cross-linked polymer in which organic and inorganic blocks are covalently interconnected and form a three-dimensional network structure. Figure 5 shows the diagram of the network PU structures formed upon application of the conventional BDO curing agent, the mixed system, and the MQ resin.

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of the prepolymer-based polyurethane networks obtained using 1,4-butanediol,

the MQ resin, and their mixture as curing agents.

Experimental section

Synthesis of the MQ resin. The MQ resin with an oxymethyldimethylsiloxane framework (MQ1) was synthesized according to the published procedure [15] in 91% yield. The oligomer is a white powder, soluble in acetone, ethanol and methanol. Its structural formula is as follows:

Anal. Calcd: C, 22.91; H, 5.77; Si, 35.72. Found: C, 23.01; H, 6.13; Si, 35.55%. The content of hydroxy groups (calc/found): 10.81/10.82%. 1H NMR (acetone-d6): δ 3.52 (2H HOCH2Si), 0.39 (6H, SiCH3) ppm. M:Q ratio = 1:1.

The structural formula of the MQ resin with an oxyethoxymethyldimethylsiloxane framework (MQ2) (M:Q = 1:1) is as follows:

A round-bottom flask equipped with a stirring bar and a backflow condenser was charged with 1,1-dimethylsila-2,5-dioxacyclohexane (86.54 g, 0.64 mol), tetraethoxysilane (133.23 g, 0.64 mol), water (57 g, 3.2 mol), sulfuric acid (4.35 g, 2% from the mass of the reagents), and dioxane (425 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 10 h. After cooling, sodium acetate (8 g, 10% excess) was added to neutralize sulfuric acid. The resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h, then the precipitate was filtered off and the filtrate was evaporated on a rotary evaporator. The residue obtained was dissolved in a mixture of acetone (250 mL) and toluene (100 mL). The precipitate formed was filtered off, and the filtrate was evaporated on a rotary evaporator to constant mass to give 112.3 g of the target product as a colorless transparent mass. Yield: 92%. Anal. Calcd: C, 29.83; H, 6.51; Si, 27.90. Found: C, 28.94; H, 6.78; Si, 27.75%. The content of hydroxy groups (calcd/found): 8.44/8.56%. 1H NMR (acetone-d6): δ 3.83 (2H, HOCH2CH2), 3.69 (2H, CH2CH2OCH2), 3.42 (2H, OCH2Si), 0.42 (6H SiCH3) ppm.

Synthesis of the urethane prepolymer and conditions for its curing. The urethane prepolymer was obtained from Laprol 3003 polyetser with a hydroxy number of 52.3 mgKOH/g and water content of 0.04%. Directly prior to use, the polyester was evacuated at 120 °C for 2 h. 2,4-Toluene diisocyanate (2,4-TDI) (98%) was purchased from ABCR and used without purification.

The urethane prepolymers were prepared according to the published procedure [16] through the reaction of a small excess of 2,4-TDI with a trifunctional polyester (νNCO:νOH = 3.3:1) at 70–75 °C. The reaction scheme is depicted in Fig. S2 in the ESI.

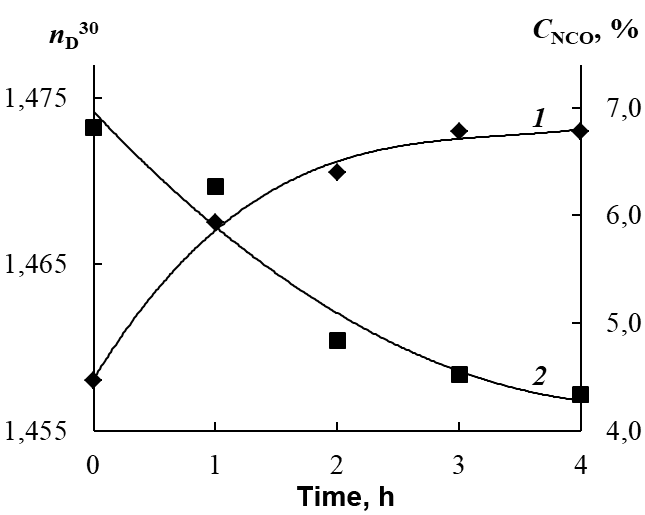

The reaction course was monitored by determining the mass fraction of NCO groups during back titration of 0.2 M solution of dibutylamine in toluene with 0.1 M solution of HCl in the presence of the bromophenol blue indicator [17], as well as by measuring the refractive index of the reaction mixture nD30 (Fig. 6). Heating was stopped when the mass fraction of NCO groups reached the value calculated based on the reaction scheme; heating duration was 4 h.

Figure 6. Kinetics of changes in the refractive index (1) and concentration of NCO groups (2) for the urethane prepolymer based on Laprol 3003.

The urethane prepolymer was a colorless viscous product. According to the results of IR spectroscopic study, it lacks OH groups, which can be identified by a broad band at 3400–3500 cm–1. A broad band at 3300 cm–1 appeared as a result of the formation of urethane groups. An intensive narrow band at 2270 cm–1 can be attributed to NCO groups.

To obtain block polyurethane compositions, cross-linking agents 1,4-butanediol (BDO), the MQ resins, or a mixture of BDO and the MQ resin were added to the prepolymer. The resins were preliminarily dissolved in acetone.

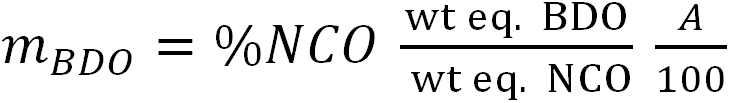

The required amount of BDO (4.269 wt parts per 100 wt parts of the prepolymer) was calculated using the following formula:

|

(1) |

Here A is the calculated percentage of stoichiometry, which was taken as 100%, since at this value, it is assumed that all NCO groups of the prepolymer react with OH groups of BDO.

When preparing the cross-linked polyurethane based on a trifunctional prepolymer, the MQ resins with hydroxy groups were considered as polyols. The required amount was calculated from the stoichiometric ratio: 3 mol of the MQ resin per 1 mol of the prepolymer.

Since an excess of NCO groups leads to the formation of allophonate and biuret groups due to the secondary processes, the amount of the MQ resins can be varied within wide limits.

When obtaining the samples with two curing agents (MQ and BDO), the calculation schemes described above were used, given the fact that each component requires half of the available NCO groups for binding.

After thorough stirring and degassing, the resulting compositions were poured into fluoroplastic molds. The curing in casting molds was carried out with a stepwise temperature rise from 60 to 100 °C with 20 °C steps at the seasoning time of 2 h. The samples obtained on the basis of MQ1 were transparent colorless films. The films based on MQ2 had a yellow tint.

The 1H and 29Si NMR spectra of the MQ resins were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer at an operating frequency of 400.13 MHz for 1H.

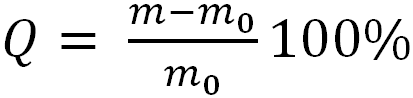

The degree of swelling (Q, %) of the polymer samples in acetone was determined by the gravimetric method:

,

,

where m, m0 are the masses of the swollen and initial (before immersion into the solvent) samples. The duration of swelling was 7 days. The samples were weighed on a HR-100 AZG (A&D) analytical balance with 0.0002 g precision.

The content of the gel fraction in the resulting polymer samples was determined by extraction in boiling acetone in a Soxhlet extractor.

The density was determined by hydrostatic weighing in isopropanol [18]. The method consists in the comparison of the masses of equal volumes of the test sample and a working liquid with a known density.

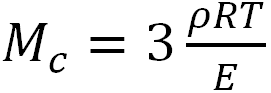

The molecular weight of a cross-link unit was calculated using the following formula:

,

,

where ρ is the density of the cross-linked elastomer, R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, and E is the elastic modulus.

Mechanical properties under uniaxial tension were measured using an LR5Kplus instrument (Lloyd Instruments). The stretching of samples with a working part size of 25 mm (total length 75 mm) was carried out at a rate of 50 mm/min.

The glass transition temperature of the samples was determined by thermomechanical analysis using a TMA Q400 unit (TAInstruments, USA) at a heating rate of 5 °C/min and a load of 1 N, using a probe with a diameter of 2.54 mm.

The thermogravimetric analysis of the samples was carried out on a DTG-60H apparatus (Shimadzu) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min in air.

Conclusions

The cross-linked polyurethanes were obtained using the MQ resins with oxymethyldimethylsiloxane or oxyethoxymethyldimethylsiloxane groups, their mixtures with 1,4-butanediol, and neat1,4-butanediol as curing agents. It was found that the MQ resins bearing hydroxy groups act as polyols during curing of the urethane prepolymer. The resulting network PU represents a hybrid organic–inorganic polymer, in which the bulk cross-link moieties are of inorganic nature and the surface groups are chemically bound with the polymer matrix.

The PUs obtained using only the MQ resins in 0.50 ppm concentration showed better physico-mechanical characteristics than those obtained based on a mixture of curing agents and neat BDO. The glass transition temperatures of the resulting compositions remained almost unchanged, while their thermal stability decreased compared to the samples cured only with BDO.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement no. 075-00277-24-00).

Electronic supplementary information

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available online: full thermogravimetric curves of the resulting PUs; scheme for the synthesis of the urethane prepolymer. For ESI, see DOI: 10.32931/io2311a

References

- M. F. Sonnenschein, Polyurethanes. Science, Technology, Markets, and Trends, Wiley, Midland, 2015.

- M. Babar, G. Verma, Prog. Org. Coat., 2023, 183, 107746. DOI: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.107746

- T. Chen, H. Wu, W. Zhang, J. Li, F. Liu, E.-H. Han, Prog. Org. Coat., 2023, 185, 107876. DOI: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.107876

- D. Tian, F. Wang, Z. Yang, X. Niu, Q. Wu, P. Sun, Carbohydr. Polym., 2019, 219, 191–200. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.05.029

- M. Zahra, H. Ullah, M. Javed, S. Iqbal, J. Ali, H. Alrbyawi, Samia, N. Alwadai, B. I. Basha, A. Waseem, S. Sarfraz, A. Amjad, N. S. Awwad, H. A. Ibrahium, H. H. Somaily, Inorg. Chem. Commun., 2022, 144, 109916. DOI: 10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109916

- F. Dolatzadeh, S. Moradian, M. Mehdi Jalili, Corros. Sci., 2011, 53, 4248–4257. DOI: 10.1016/j.corsci.2011.08.036

- C.-a. Xu, Z. Qu, Z. Tan, B. Nan, H. Meng, K. Wu, J. Shi, M. Lu, L. Liang, Polym. Test., 2020, 86, 106485. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106485

- K. N. Raftopoulos, B. Janowski, L. Apekis, P. Pissis, K. Pielichowski, Polymer, 2013, 54, 2745–2754. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.03.036

- S. Koutsoumpis, J. Ozimek, K. N. Raftopoulos, E. Hebda, P. Klonos, C. M. Papadakis, K. Pielichowski, P. Pissis, Polymer, 2018, 147, 225–236. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.06.012

- E. Tatarinova, N. Vasilenko, A. Muzafarov, Molecules, 2017, 22, 1768. DOI: 10.3390/molecules22101768

- I. B. Meshkov, A. A. Kalinina, V. V. Kazakova, A. I. Demchenko, INEOS OPEN, 2020, 3, 118–132. DOI: 10.32931/io2022r

- X. Shi, Z. Chen, Y. Yang, Eur. Polym. J., 2014, 50, 243–248. DOI: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.11.005

- P. Jia, H. Liu, Q. Liu, X. Cai, Polym. Degrad. Stab., 2016, 134, 144–150. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.09.029

- I. B. Meshkov, A. A. Kalinina, V. V. Gorodov, A. V. Bakirov, S. V. Krasheninnikov, S. N. Chvalun, A. M. Muzafarov, Polymers, 2021, 13, 2848. DOI: 10.3390/polym13172848

- N. V. Sergienko, T. V. Strelkova, K. L. Boldyrev, L. I. Makarova, A. S. Tereshchenko, INEOS OPEN, 2019, 2, 196–199. DOI: 10.32931/io1928a

- A. A. Askadskii, L. M. Goleneva, E. S. Afanas'ev, M. D. Petunova, Rev. J. Chem., 2012, 2, 263–314. DOI: 10.1134/S2079978012030028

- ISO 11909-2007: Binders for paints and varnishes. Polyisocyanate resins. General methods of test, 2007.

- GOST (State Standard) 15139-69: Plastics. Methods for the determination of density (mass density), 1969.