2023 Volume 6 Issue 1

|

INEOS OPEN, 2023, 6 (1), 16–20 Journal of Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds Download PDF |

|

Polyphenylene Impregnated with Fullerene C60-Containing Oligophenylenes

for CO2 Adsorption

А. S. Dorofeev,a S. N. Filatov,b and I. A. Khotina*a

a Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Vavilova 28, str. 1, Moscow, 119334 Russia

b Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology, Miusskaya pl. 9, str. 1, Moscow, 125047 Russia

Corresponding author: I. A. Khotina, e-mail: khotina@ineos.ac.ru

Received 13 October 2023; accepted 15 November 2023

Abstract

A network porous polyphenylene and fullerene-containing branched oligophenylenes have been synthesized to produce the polyphenylenes impregnated with the fullerene-containing compounds for CO2 adsorption. The resulting compounds were studied by IR spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The analysis of the specific surface area was performed using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory. The samples were tested tested for the efficiency of carbon dioxide adsorption. The most effective carbon dioxide adsorbent is found to be the polyphenylene impregnated with a triphenylamine-containing fullerene derivative.

Key words: porous adsorption materials, polyphenylenes, CO2 adsorption, fullerene C60-containing oligophenylenes.

Introduction

Microporous materials are becoming more popular every year owing to a wide application scope, which includes the sorption technologies, gas storage, heterogeneous catalysis, etc. Therefore, the creation and investigation of new microporous polymeric materials is an urgent and promising task [1, 2].

The most common microporous materials are crystalline inorganic compounds (e.g., zeolites and related structures) or amorphous network structures (e.g., silica, activated carbon). However, the last decade has seen a considerable progress in the creation of microporous materials involving organic components [3–7].

Of particular interest are the microporous polymeric materials based on rigid monomers. These polymers may have network structures. Thus, the specific surface area of most of the network polymers ranges within 700–1300 m2/g [8,9] and can even reach 3500 m2/g [6, 10].

One of the main challenges of modern ecology is the storage and utilization of carbon dioxide which is formed during the conversion of fossil fuels to electricity, the production of cement, iron and steel, and different processes in the petrochemical industry.

The technologies such as carbonic acid capture and storage can provide a significant reduction in anthropogenic emissions [11]. To date, a number of separation technologies have been studied, including physical and chemical absorption. Adsorption is preferred as a basic and effective tool for separating gas mixtures in industrial processes due to its advantages which include precursor availability and simple regeneration [12].

There are a multitude of materials and techniques that are used to adsorb carbon dioxide. The main options are the use of sorbents in their pure form, the application of gas-adsorbing materials on the substrate, and the impregnation of a matrix with a gas-adsorbing material, most frequently some amines [13]. For example, the selectivity of a polymer deprived of nitrogen atoms relative to CO2 in gas mixtures is not high enough due to the realization of the physical adsorption mechanism. However, the introduction of an adsorbent bearing an amino group increases the selectivity due to a change in the adsorption mechanism from physical to chemical. It is also noteworthy that pore sizes directly affect the adsorption capacity of impregnated materials, and the porous material provides more efficient interaction of amine-containing compounds with CO2 [14–17].

Results and discussion

Among porous polymers, polyphenylenes are distinguished by the high chemical and thermal stability, as well as high strength. Under certain synthesis conditions and subsequent activation, they can afford porous materials that are promising as matrices for the sorption of carbon dioxide [18].

The polycyclocondensation of acetylaromatic compounds, which leads to the formation of new 1,3,5-trisubstituted benzene rings, was chosen as the main method for the synthesis of polyphenylenes in this work [19, 20]. The advantage of this method is that the condensation results in branched polymers with terminal acetyl groups, the presence of which enables the production of thermally and heat-resistant network polymers as a result of thermal structuring. The resulting network polymers are, at the same time, microporous carbon materials with a specific surface area of up to 600–800 m2/g [18–20]. They also feature high strength, chemical and thermal stability and, therefore, can be used as highly heat-resistant sorbents.

In this work, the porous polyphenylene matrices were synthesized and then impregnated with CO2 adsorbents to study the adsorption capacity of the new sorption systems.

The target network polyphenylene was obtained based on p-diacetylbenzene in two stages via the cyclocondensation of acetylaromatic compounds (Fig. 1) [19, 20]. At the first stage, hydrogen chloride gas was passed through a solution of p-diacetylbenzene, a nonpolar aromatic solvent, and o-formic acid ester at room temperature. The resulting insoluble gel (P1), containing residual functional groups, was thermally treated at 450 °C in an argon flow for 3 h according to the published procedure [18], which promoted the production of cross-linked polyphenylene P2.

Figure 1. Synthesis of polyphenylene P2.

The IR spectrum of P1 shows the absorption bands at 3030, 2925, 1682, 1655, 1600, 1509, 1263, and 819 cm–1, characteristic of the C–H bond stretching vibrations of the benzene rings and acetyl groups, C=O bond stretching vibrations of the acetyl and dipnone units (the products of dimerization of acetyl groups), in-plane stretching vibrations of the phenylene moieties (two bands at 1600 and 1509 cm–1), vibrations of arylalkyl ketones, and out-of-plane C–H bond vibrations of the benzene rings, respectively, as well as weak absorption bands at 880, 760, and 700 cm–1 attributed to 1,3,5-phentriyl moieties bound to other aromatic moieties. Compared to the spectrum of P1, in the spectrum of P2 the bands at 1680, 1655, and 1262 cm–1 practically disappeared and the absorption bands at 880, 760, and 700 cm–1 increased significantly, which indicates a high degree of conversion of the reactive groups and moieties and an increase in the number of 1,3,5-substituted benzene rings, which are the branching centers of the polymer molecules.

According to the results of the specific surface area studies using the BET theory, the structure of P2, analogously to the results obtained earlier [18], has a large amount of free space due to the rigidity of all polymer units, as well as due to rod-shaped internodal fragments and symmetrically branched points of the polymer network [19]. The specific surface area of this polymer is about 650 cm2/g.

It is known that fullerene C60 improves the gas separation ability of various materials [21, 22]. Despite the polarization ability and high chemical activity, fullerene has outstanding stability. For example, C60 sublimes without decomposition at 873 K. Apparently, the compounds containing polyphenylene and fullerene structural units can be promising materials for the adsorption of various gases, where polyphenylene acts as a porous matrix [23].

The addition of N-containing functional groups to the surfaces of adsorbents is one of the most popular ways to improve CO2 sorption through chemisorption.

Amino acid derivatives of fullerene (AADFs) 1 and 2 were synthesized according to the earlier described method [24, 25]. The synthetic scheme is depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Synthesis of compounds 1 and 2.

The fullerene derivatives, in this case compounds 1 and 2, have an active hydrogen atom on the C60 framework, which can readily react with halides.

To obtain the fullerene-containing aromatic compounds that could serve as CO2 sorbents, 1,3,5-tris(p-bromodiphenyl)benzene (3) and 4-bromo-N,N-diphenylaniline (4) were used as starting compounds. Both compounds were characterized by the 1H NMR spectra.

When reacting with bromides, mono(amino acid) derivatives of fullerene (MAADFs) behave as ionogenic surfactants having a polar group, the charge of which is opposite in sign to the surface charge. The modification of phenylene compounds with AADF solutions leads to the hydrophilization of their surfaces, as in the case of low-molecular-weight surfactants.

Bromine-containing phenylene compound 3 reacted with a MAADF, namely, N-(monohydrofullerenyl)-l-valine methyl ester (1) (Fig. 3), while 4-bromo-N,N-diphenylaniline 4 reacted with another MAADF, namely, N-(monohydrofullerenyl)-α-aminocaproic acid methyl ester (2) (Fig. 4). The reactions were carried out in pyridine since both the starting compounds and the products were highly soluble in this solvent. However, during isolation, starting fullerene derivatives 1 and 2 appeared to be soluble in pyridine, but not soluble in water. To accomplish the synthesis, in all cases, an excess of compound 1 or 2 was used. To separate the target products from the excess fullerene derivative, they must be converted to a water-soluble form. For this purpose, after the reaction completion, ethylene chlorohydrin was added to the mixture in pyridine, which forms a water-soluble form upon interaction with the fullerene amino derivative. Therefore, when the final product is dialyzed against water, the desired compound precipitates and can be collected by centrifugation [24, 25].

Figure 3. Synthesis of compound 5.

Figure 4. Synthesis of compound 6.

The IR spectrum of compound 5 shows the absorption bands at 3315 and 1707 cm–1, characteristic of the N–H bond stretching vibrations in the amino acid unit and the C=O stretching vibrations of the carboxyl group, as well as three peaks at 1100, 951, and 886 cm–1, which can be attributed to the fullerene core.

The IR spectrum of compound 6 shows the absorption bands characteristic of aromatic units (1074, 1387–1483, 1630 cm–1), as well as the absorption bands characteristic of fullerene (953, 1179 cm–1). In addition, this spectrum contains a band at 1709 cm–1, which belongs to the carbonyl group of the amino acid moiety.

The molar masses of compounds 5 and 6 were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) in N-methylpyrrolidone. The results obtained are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Molecular mass characteristics of the resulting compounds according to the GPC data

|

Comp.

|

Calc. mass, Da

|

Мn

|

Мw

|

D (polydispersity coeff.)

|

|

5

|

3083

|

4383

|

8263

|

1.885

|

|

6

|

1108

|

2497

|

7035

|

2.817

|

According to the results obtained, it can be concluded that these compounds are prone to aggregation in solution, which is typical for fullerene-containing derivatives.

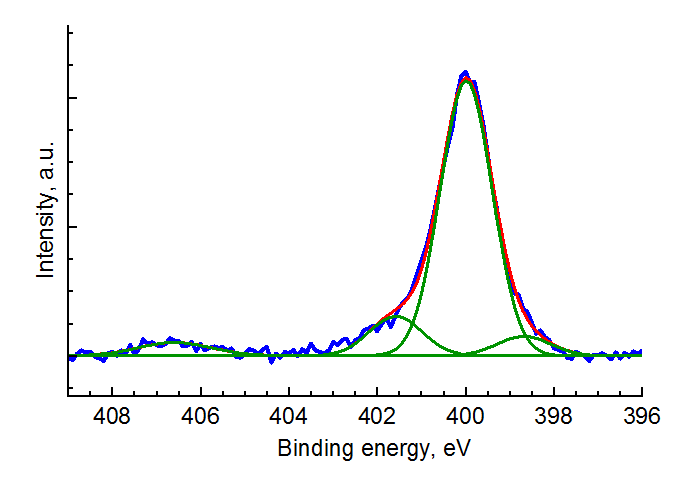

Chemical elements differ in atomic structures. Measuring the binding energy of electrons in atoms of the compound under investigation (the positions of spectral lines), it is possible to obtain information about the electronic structure of the atoms and, thereby, identify chemical elements. One of the best methods for identifying fullerene and its derivatives is X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Figure 5 shows the high-resolution N 1s XPS spectrum for compound 6. Table 2 shows the results of calculations of element concentrations on the surface of the samples explored derived from the high-resolution XPS spectra.

Figure 5. High-resolution N 1s XPS pattern for 6.

Table 2. Element concentrations on the surface of the samples explored (at %) calculated from the high-resolution XPS spectra

|

Sample

|

O

|

C

|

N

|

K

|

Br

|

Cl

|

|

Р2

|

0.6

|

98.5

|

|

|

|

0.9

|

|

1

|

19.9

|

73.7

|

1.5

|

3.7

|

|

1.3

|

|

5

|

15.9

|

81.8

|

2.3

|

|

n/d

|

|

|

6

|

8.6

|

87.6

|

2.9

|

|

0.9

|

|

| n/d—not detected. |

The absence (or low content) of bromine in samples 5 and 6 confirms the formation of the target products. The presence of excess nitrogen in the sample may indicate the presence of crystal solvate pyridine molecules [25].

To test the ability of the resulting sorbents to adsorb carbon dioxide, polymer P2 was impregnated with compounds 5 and 6, followed by their treatment with supercritical CO2. For impregnation, a solution of 5 or 6 in pyridine was added dropwise to dry P2 until it was saturated, and then the resulting sample was dried.

The analysis of the IR spectra of compound 5, matrix P2 after saturation with CO2, and P2 impregnated with compound 5 and saturated with CO2 indicates the appearance of a band in the region of 1790–1810 cm–1, responsible for the carbonyl group, in the compounds saturated with CO2.

Table 3 lists the characteristics of polyphenylene matrix P2 before and after the impregnation with compounds 5 and 6 and the saturation with CO2.

Table 3. Characteristics of polyphenylene matrix P2 prior to and after the impregnation with compounds 5 and 6 and saturation with CO2

|

Sample

|

Comp.

|

Mass increment of P2 upon impregnation with 5 or 6, %

|

Specific surface area according to the BET analysis

m2·g–1

|

СО2 increment in 15 min after pressure removal

|

|

I

|

P2

|

–

|

650

|

19

|

|

II

|

P2+5

|

23

|

20

|

34

|

|

III

|

P2+6

|

67

|

33

|

70

|

The data presented in Table 3 allow us to conclude that the specific surface area of the polyphenylene matrix impregnated with the fullerene-containing compounds decreases significantly. This can be explained by the fact that compounds 5 and 6 fill the pores of polyphenylene matrix P2. Despite this, the adsorption of carbon dioxide by samples II and III, containing the fullerene derivatives, is significantly higher than that provided by sample I (Table 3), which is probably can be associated with the insufficiently high adsorption capacity relative to CO2 in gas mixtures for polyphenylenes due to the realization of the physical adsorption mechanism, but the introduction of the fullerene compounds containing an amino group increases the adsorption capacity and selectivity due to a change in the adsorption mechanism from physical to chemical.

It should be noted that a small part of carbon dioxide remained in the samples even after several days, as it was judged from the mass increment as well as the IR spectroscopic data, where the absorption band of the carbonyl group from CO2 remained. Presumably, the degree of carbonylation of the aromatic framework is insignificant.

Experimental section

The XPS spectra were recorded with an Axis Ultra DLD (Kratos, Manchester, UK) spectrometer using monochromated Al–Kα radiation. The energy scale was calibrated to provide the following values for the reference metal surfaces freshly purified by ion bombardment: Au 4f7/2 83.96 eV, Cu 2p3/2 932.62 eV, and Ag 3d5/2 368.21 eV. The electrostatic charging effects were compensated by using an electron neutralizer. Sample charging was corrected by referencing to the C–C/C–H group identified in the C 1s spectrum (284.8 eV). After charge referencing, a Shirley-type background with inelastic losses was subtracted from the high-resolution spectrum.

The IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor-37 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

The 1H NMR spectra were registered on a Bruker Avance-400 spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) operating at a frequency of 400.13 MHz. The sample solutions were prepared in deuterated chloroform. The chemical shifts are given in ppm, and the calibration was carried out relative to the signal of the solvent residual proton.

The GPC analysis performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity GPC unit was used to determine the molar masses of compounds 5 and 6.

The porous structure of the polymers was studied with a NOVA 1200e unit (Quantachrome Instruments, USA) for the analysis of specific surface area and porosity. The calculations were performed using the NOVAWin software (version 11.04) with a built-in package of computation algorithms based on the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory. Nitrogen was used as the sorbing gas, and the nitrogen sorption measurement temperature was 77 K.

Triethyl orthoformate (1,1,1-triethoxymethane, TEOF) was distilled under argon over K2CO3, collecting a fraction boiling at 143–145 °C. Benzene was distilled under argon over sodium, collecting a fraction boiling at 79–80 °C.

1,3,5-Tris(p-bromodiphenyl)benzene (3). A 100 mL flask was charged with 5.0 g (18.0 mmol) of 4-bromodiphenylacetophenone, 8.93 mL (0.1 mol) of benzene, and 3.59 mL (21.6 mmol) of triethyl orthoformate at room temperature. Gaseous HCl, obtained by reacting concentrated sulfuric acid with sodium chloride, was passed through the solution for 1 h. Then the reaction mixture was poured into ethanol upon vigorous stirring. The precipitated product was collected by filtration, rinsed with ethanol, and dried. The yield of the product after recrystallization from chloroform was 26%. Mp: 278–279 °C. Anal. Calcd for C42H27Br3: C, 65.37; H, 3.50; Br, 31.13. Found: C, 65.48; N, 3.16; Br, 31.36%.

4-Bromo-N,N-diphenylaniline (4) (Aldrich) and 1,4-diacetylbenzene (ABCR) were purchased from commercial sources and used without purification.

Branched polyphenylenes P1 and P2 were obtained according to the previously published procedure [20].

N-(Monohydrofullerenyl)-l-valine methyl ester (1) (fullerene C60). The synthesis was carried out according to the previously described method [24]. The yield was quantitative.

N-(Monohydrofullerenyl)-α-aminocaproic acid methyl ester (2) (fullerene C60). The synthesis was carried out analogously the synthesis of compound 1. In this case, a potassium salt of α-aminocaproic acid was used. The yield was close to quantitative.

Phenylene sorbent 5 was synthesized according to the published procedure [24]. Compound 5 was characterized by the IR and XPS spectra, its molecular weight characteristics were determined using GPC.

Triphenylamine-based sorbent 6 was prepared according to the following procedure. 32.4 mg of 4-bromo-N,N- diphenylaniline (4) (0.10 mmol) was added to a solution of 104 mg (0.12 mmol) of N-(monohydrofullerenyl)-α-aminocaproic acid methyl ester (2) in 5 mL of pyridine. The reaction mixture was refluxed under an argon atmosphere for 8 h and left overnight at an ambient temperature. The resulting mixture was dialyzed against water. The precipitate obtained was centrifuged and dried. The yield was close to quantitative. The molecular weight characteristics of compounds 5 and 6 were determined using GPC.

Impregnation of cross-linked polymer P2 with compounds 5 and 6. Polyphenylene P2 was placed in a test tube, then a solution of compound 5 in pyridine was added dropwise in portions. After each portion, a break was taken and the dropwise addition was repeated until the moment when the solution was no longer absorbed into the polymer matrix. After several hours, polymer matrix P2 with impregnated compound 5 was dried and used for further studies. A similar procedure was performed for compound 6.

Saturation of samples I–III with carbon dioxide. A portion of the test sample was weighed on a balance, and the result was recorded to four digits. The sample was placed in a PE tube, which was also preliminary weighed. Then the sample in the tube and the control sample of an empty PE tube were placed in an autoclave, where CO2 saturation was carried out for 12 h under a pressure of 50 atm. The tube with the sample and the control empty tube were weighed. The data from weighing the empty PE tube showed that this material does not adsorb CO2, and, consequently, the use of such containers does not affect the results of gas adsorption studies. Then the difference in the mass increment of samples I–III was used to determine the amount of adsorbed carbon dioxide.

Conclusions

Using the cyclotrimerization reaction, porous polyphenylene matrix P2 as well as compounds 5 and 6 having fullerene and branched phenylene frameworks were obtained. The resulting compounds were studied by IR spectroscopy, BET, and XPS. The ability of the sorbents containing compounds 5 and 6 to adsorb carbon dioxide upon treatment with supercritical CO2 after their impregnation into polyphenylene matrix P2 was experimentally evaluated. It was shown that the impregnation of the matrix with the fullerene-containing compounds reduces the specific surface area of the matrix in 18–30 times, but increases the CO2 absorption in 1.8–3.7 times, which indicates that the resulting sorbents are promising for CO2 adsorption. Further modification of these matrices and compounds will improve the affinity of adsorbents for carbon dioxide, for its more complete extraction from combustion gases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 19-73-20262).

Electronic supplementary information

The IR and 1H NMR spectra of the compounds obtained. For ESI, see DOI: 10.32931/io2303a

References

- N. Chaoui, M. Trunk, R. Dawson, J. Schmidt, A. Thomas, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2017, 46, 3302–3321. DOI: 10.1039/c7cs00071e

- A. Fuoco, C. Rizzuto, E. Tocci, M. Monteleone, E. Esposito, P. M. Budd, M. Carta, B. Comesaña-Gándara, N. B. McKeown, J. C. Jansen, J. Mater. Chem. A., 2019, 7, 20121–20126. DOI: 10.1039/C9TA07159H

- M. Eddaoudi, J. Kim, N. Rosi, D. Vodak, J. Wachter, M. O'Keeffe, O. M. Yaghi, Science, 2002, 295, 469–472. DOI: 10.1126/science.1067208

- M. Eddaoudi, D. B. Moler, H. Li, B. Chen, T. M. Reineke, M. O'Keeffe, O. M. Yaghi, Acc. Chem. Res., 2001, 34, 319–330. DOI: 10.1021/ar000034b

- G. Férey, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2008, 37, 191–214. DOI: 10.1039/b618320b

- H. M. El-Kaderi, J. R. Hunt, J. L Mendoza-Cortés, A. P. Côté, R. E. Taylor, M. O'Keeffe, O. M. Yaghi, Science, 2007, 316, 268–272. DOI: 10.1126/science.1139915

- A. P. Côté, A. I. Benin, N. W. Ockwig, M. O'Keeffe, A. J. Matzger, O. M. Yaghi, Science, 2005, 310, 1166–1170. DOI: 10.1126/science.1120411

- J.-X. Jiang, F. Su, A. Trewin, C. D. Wood, H. Niu, J. T. A. Jones, Ya. Khimyak, A. I. Cooper, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 7710–7720. DOI: 10.1021/ja8010176

- E. Stöckel, X. Wu, A. Trewin, C. D. Wood, R. Clowes, N. L. Campbell, J. T. A. Jones, Ya. Khimyak, D. J. Adams, A. I. Cooper, Chem. Commun., 2009, 212–214. DOI: 10.1039/B815044C

- J.-S. M. Lee, A. I. Cooper, Chem. Rev., 2020, 120, 2171–2214. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00399

- M. Carta, K. J. Msayib, N. B. McKeown, Tetrahedron Lett., 2009, 50, 5954–5957. DOI: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.08.032

- M. Carta, K. J. Msayib, P. M. Budd, N. B. McKeown, Org. Lett., 2008, 10, 2641–2643. DOI: 10.1021/ol800573m

- H. Furukawa, O. M. Yaghi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 8875–8883. DOI: 10.1021/ja9015765

- S. Yadav, S. S. Mondal, Fuel, 2022, 308, 122057. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122057

- P. G. Ghougassiana, J. A. Pena López, V. I. Manousiouthakis, P. Smirniotis, Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control, 2014, 22, 256–271. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.12.004

- H. Zeng, X. Qu, D. Xu, Y. Luo, Front. Chem., 2022, 10, 939701. DOI: 10.3389/fchem.2022.939701

- J. A. A. Gibson, A. V. Gromov, S. Brandani, E. E. B. Campbell, Microporous Mesoporous Mater., 2015, 208, 129–139. DOI: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.01.044

- A. I. Kovalev, A. V. Pastukhov, E. S. Tkachenko, Z. S. Klemenkova, I. R. Kuvshinov, I. A. Khotina, Polym. Sci., Ser. C, 2020, 62, 205–213. DOI: 10.1134/S1811238220020071

- A. I. Kovalev, E. S. Mart'yanova, I. A. Khotina, Z. S. Klemenkova, Z. K. Blinnikova, E. V. Volchkova, T. P. Loginova, I. I. Ponomarev, Polym. Sci., Ser. B, 2018, 60, 675–679. DOI: 10.1134/S156009041805007X

- I. A. Khotina, O. A. Filippov, A. I. Kovalev, Mendeleev Commun., 2020, 30, 366–368. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2020.05.035

- E. R. Badamshina, M. P. Gafurova, Polym. Sci., Ser. B, 2008, 50, 215–225. DOI: 10.1134/S1560090408070142

- L. V. Vinogradova, G. A. Polotskaya, A. A. Shevtsova, A. Yu. Alent'ev, Polym. Sci., Ser. A, 2009, 51, 209–215. DOI: 10.1134/S0965545X09020102

- A. I. Kovalev, S. A. Babich, M. A. Kovaleva, N. S. Kushakova, Z. S. Klemenkova, Z. K. Blinnikova, A. Yu. Popov, I. A. Khotina, Polym. Sci., Ser. B, 2022, 64, 155–160. DOI: 10.1134/S156009042201002X

- V. S. Romanova, I. A. Khotina, N. S. Kushakova, A. I. Kovalev, V. G. Kharitonova, D. V. Kupriyanova, A. V. Naumkin, Mendeleev Commun., 2022, 32, 783–785. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2022.11.025

- V. S. Romanova, V. A. Tsyryapkin, Yu. I. Lyakhovetsky, Z. N. Parnes, M. E. Vol'pin, Russ. Chem. Bull., 1994, 6, 1090–1091. DOI: 10.1007/BF01558092