2023 Volume 6 Issue 2

|

INEOS OPEN, 2023, 6 (2), 55–61 Journal of Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds |

|

Polydimethylsiloxanes with Grafted Naphthalene Fragments: Synthesis and Properties

a Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Vavilova 28, str. 1, Moscow, 119334 Russia

b Photochemistry Center, FSRC "Crystallography and Photonics", Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Novatorov 7A, str. 1, Moscow, 119421 Russia

Corresponding author: Yu. N. Kononevich, e-mail: kononevich.yuriy@gmail.com

Received 5 October 2023; accepted 27 November 2023

Abstract

Nowadays, the synthesis and investigation of the properties of new fluorescent polymers based on polysiloxanes and organic fluorophores is an actual topic of research. These polymers find application in various fields of science and technology, in particular, as sensors, fluorescent covers, and optical materials. This work describes the method for obtaining new naphthalene end-capped and side-chain modified polydimethylsiloxanes. The physicochemical, optical, and thermal properties of the resulting polymers are thoroughly studied.

Key words: polysiloxanes, naphthalene, hydrosilylation, fluorescence, excimer.

Introduction

At present, naphthalene and its derivatives comprise the most studied class of organic dyes with valuable optical properties, including the ability to form fluorescent excimers in the excited state [1–12]. The most interesting and promising representatives of these dyes are naphthalene-containing polymers of different architecture since they can be utilized as the materials that are able to change their optical properties under external impact [13–21]. Naphthalene moieties were included in the structures of poly-l-glutamate [14], polyamide [22], and methacrylate [15, 18–21].

Polysiloxanes are remarkable polymers that are widely used in various fields of science and technology as the components of paints [23], electroinsulating materials [24, 25], sealing compounds [26], components of semiconducting materials [27], as well as the optical materials [28]. Excellent biocompatibility of polysiloxanes make them highly useful in cosmetics, pharmaceutics, and medicine [29–33]. Silanes and siloxanes of different structure modified with various fluorophores are very attractive objects for optic, photonic and imaging applications. First of all, this is stipulated by the optical transparency of organosilicon matrices and the ease of their modification with required chromophores. Of particular interest as matrices are polysiloxanes since the developed synthetic methods allow one to modify them over a wide range. In these polymers, the distance between the grafted chromophores could be easily regulated, thus enabling fine-tuning of the optical properties [34–36]. Earlier the multifunctional naphthalene-containing systems based on silane [37], siloxane [38, 39], cyclosiloxane [39–41], silsesquioxane [42], and polysiloxane [43–45] matrices were reported. Therefore, the synthesis of new polysiloxanes with naphthalene substituents and investigation of their properties in the context of development of new promising optical materials is currently an actual topic of research.

Herein, we report the synthesis of new naphthalene end-capped and side-chain modified polydimethylsiloxanes as well as their physicochemical, optical, and thermal properties.

Results and discussion

In the present work, polydimethylsiloxanes with terminal silylhydride groups (M1) and those distributed along the chain (M2) were used as silicone matrices for grafting naphthalene fragments (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Structures of the polysiloxane matrices with terminal silylhydride groups (M1) and those distributed along the chain (M2),

as well as model naphthalene derivative MonoNaph.

Polymer M1 was prepared by the cationic ring-opening polymerization of octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) using tetramethyldisiloxane as a chain terminator and Amberlyst 15 as a catalyst. Polymer M2 was synthesized in the same manner from D4 and heptamethylcyclotetrasiloxane using hexamethyldisiloxane as a chain terminator and Amberlyst 15 as a catalyst by the method described earlier [46]. Polysiloxanes M1 and M2 were obtained as colorless oils with the molecular characteristics presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Molecular characteristics of M1, M2, P1, and P2

|

Comp.

|

Mn, kDa

|

Mw, kDa

|

PDI

|

|

M1

|

2.5

|

4.1

|

1.66

|

|

M2

|

31.8

|

47

|

1.48

|

|

P1

|

3.6

|

5

|

1.39

|

|

P2

|

44.2

|

76

|

1.73

|

1-Allylnaphthalene was used as a functional naphthalene derivative which was prepared by the method described earlier by our research group [39]. MonoNaph was used as a model compound for comparison of its optical properties with those of resulting polymers M1 and M2 (Fig. 1) [39].

The naphthalene end-capped (P1) and side-chain modified (P2) polydimethylsiloxanes were obtained by the Pt-catalyzed hydrosilylation in toluene according to Scheme 1 and were purified by preparative gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The reaction course was monitored by NMR spectroscopy and its completion was determined by the disappearance of a signal of the Si–H group. Table 1 lists the molecular characteristics of P1 and P2.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of P1 and P2.

The photophysical properties of polymers P1, P2 were studied using electron absorption and steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy (Table 2). Figures 2 and 3 show the normalized absorption and emission spectra of P1 and P2 in cyclohexane, chloroform, and ethanol. As can be seen, the absorption and emission spectra of P1 and P2 are typical for naphthalene derivatives. However, in the case of the fluorescence spectrum of P2 in ethanol, a new broad band at 400 nm was detected that can be attributed to the emission of naphthalene excimers. In addition, there was broadening in the absorption spectrum of P2 in ethanol, which probably corresponds to naphthalene aggregates. This behavior of P2 in ethanol can be rationalized by the fact that ethanol is a poor solvent for polysiloxanes and promotes the appearance of naphthalene aggregates in solution. At the same time, the corresponding spectra of P1 do not contain the bands attributed to naphthalene aggregates and excimers. It should be noted that the optical properties of model compound MonoNaph in different solvents were studied previously and it was shown that it does not exhibit excimer fluorescence in dilute solutions [39].

Table 2. Optical properties of P1 and P2 in different solvents

|

Comp.

|

Solvent

|

λabs, nm

|

λem, nm

|

Фfa

|

Iex/Im

|

|

P1

|

Cyclohexane

|

283

|

327 (336)

|

0.43

|

0.00

|

|

Chloroform

|

285

|

336 (327)

|

0.06

|

0.00

|

|

|

Ethanol

|

283

|

327 (335)

|

0.49

|

0.00

|

|

|

P2

|

Cyclohexane

|

283

|

327 (335)

|

0.44

|

0.02

|

|

Chloroform

|

285

|

336 (328)

|

0.09

|

0.01

|

|

|

Ethanol

|

283

|

327 (335)

|

n.d.

|

0.10

|

| λabs is the absorption wavelength; λem is the emission wavelength; Фf is the fluorescence quantum yield; the wavelengths of the second fluorescence peaks are given in parentheses; a naphthalene was used as a standard for calculating the quantum yield (Фf = 0.23; argon-purged solution in cyclohexane). |

Figure 2. Normalized absorption (top) and fluorescence (bottom) spectra of P1 in different solvents at room temperature (λex = 270 nm, c = 1 μM).

Figure 3. Normalized absorption (top) and fluorescence (bottom) spectra of P2 in different solvents at room temperature (λex = 270 nm, c = 1 μM).

The absorption spectra of P1 and P2 in the condensed state are typical for naphthalene derivatives and P1-P2 in different solvents (Fig. 4, top). The fluorescence spectra of P1, P2, and MonoNaph in the condensed state, in addition to the emission of a naphthalene moiety, show an intense red-shifted band of the excimer emission (Fig. 4, bottom). As can see from Fig. 4, the content of excimers for MonoNaph is higher than in the case of polymers P1 and P2, which can be associated with the higher degree of freedom in MonoNaph to form excimers in the excited state.

Figure 4. Normalized absorption spectra of P1, P2 (top) and fluorescence spectra of P1, P2, and MonoNaph (bottom)

in the condensed state (viscous liquids, λex = 270 nm).

To quantify the intramolecular excimers in dilute solutions of P1 and P2, the corresponding fluorescence spectra were compared with those of MonoNaph measured in the same solvents. Then, the excimer/monomer ratio was found using the following equation:

|

(1) |

where Iex is the intensity of the excimer emission; Im is the intensity of the monomer emission; Iex400 is the intensity at 400 nm in the normalized emission spectra of P1 and P2 (400 nm was selected as the wavelength close to the excimer emission maximum); IMonoNaph400 is the intensity at 400 nm in the normalized emission spectra of MonoNaph; Inorm is the intensity used to normalize the emission spectra at the maximum [47]. As can be seen from the data summarized in Table 2, the highest values of Iex/Im are observed in the case of P2 in ethanol.

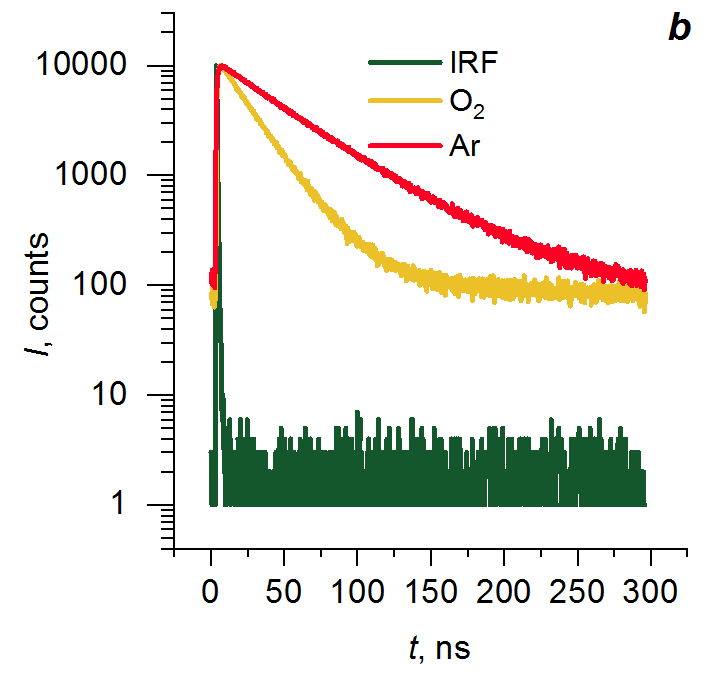

The fluorescence decay curves of P1 and P2 solutions in aerated and deaerated cyclohexane, chloroform, and ethanol registered at 335 nm are depicted in Fig. 5.

Figure 5. Fluorescence decay kinetics of P1 (a) and P2 (b) in cyclohexane, chloroform, and ethanol. The comparison of fluorescence decays

of P1 in aerated and argon-purged cyclohexane (c). All kinetic curves were obtained at the wavelength of 335 nm (λex = 275 nm).

The resulting curves are non-monoexponential and require at least two exponential terms for satisfactory (χ2 < 1.3) fitting. The fitting results are presented in Table 3. The biexponential decay seems to attribute to the interaction of fluorophore moieties during the excimer formation process. The fluorescence of P1 and P2 is effectively quenched by oxygen. After oxygen removal, the decay lifetime in cyclohexane becomes almost three times longer, as can be seen in Fig. 5c.

Table 3. Results of approximation of the fluorescence decay kinetics of the P1 and P2 solutions

in cyclohexane, chloroform, and ethanol obtained at 335 nm (λex = 275 nm)

|

Sample

|

Air

|

Ar

|

|||||

|

τ, ns

|

A, %

|

χ2

|

τ, ns

|

A, %

|

χ2

|

||

|

P1

|

C6H12

|

16.8

|

92

|

1.13

|

55.8

|

94

|

1.06

|

|

4.7

|

8

|

11.5

|

6

|

||||

|

CHCl3

|

4.5

|

82

|

1.28

|

5.6

|

82

|

1.28

|

|

|

0.9

|

18

|

1.6

|

18

|

||||

|

EtOH

|

16.7

|

89

|

1.10

|

30.6

|

88

|

1.27

|

|

|

5.9

|

11

|

9.0

|

12

|

||||

|

P2

|

C6H12

|

17.6

|

90

|

1.11

|

47.9

|

72

|

1.13

|

|

5.8

|

10

|

28.7

|

28

|

||||

|

CHCl3

|

4.9

|

74

|

1.29

|

6.0

|

75

|

1.38

|

|

|

0.9

|

26

|

1.3

|

25

|

||||

|

EtOH

|

17.8

|

55

|

1.20

|

40.3

|

57

|

1.21

|

|

|

3.9 |

45 |

5.3 |

43 |

||||

Figures 6 and 7 show the fluorescence decay kinetics of P1 and P2 in the condensed state measured at 335 and 420 nm in air and argon. The results of global fitting of the data obtained are presented in Table 4. It should be noted that all the kinetics include a significant contribution of the fast component (τ < 50 ps), which cannot be distinguished from the instrument response function (IRF). This component can be associated both with fast processes and with scattered light from the excitation source. During fitting procedure, the component in question was classified as scattered light. The resulting kinetic curves are best approximated by a model with three exponential terms (χ2 ≤ 1.3). At a wavelength of 420 nm, the fitting results contain exponential terms with a negative amplitude, which indicates the occurrence of rearrangement of the relative fluorophore positions in the excited state. The three exponential terms are presumably observed due to the presence of dimers and excimers of various structures in polymers. Their structural rearrangement into the most favorable geometry, corresponding to the excimers in solutions, is complicated by the interaction with the polymer chains. In argon, the lifetime of fluorophores increases due to reduction of effective quenching of the excited states by oxygen.

Figure 6. Fluorescence decay kinetics of polymer P1 at 335 (a) and 420 nm (b) (λex = 275 nm).

Figure 7. Fluorescence decay kinetics of polymer P2 at 335 (a) and 420 nm (b) (λex = 275 nm).

Table 4. Results of global approximation of the fluorescence decay kinetics of P1 and P2 in the condensed state (λex = 275 nm)

|

Sample

|

τ, ns

|

Aλ = 335 nm, a.u.

|

Aλ = 420 nm, a.u.

|

χ2

|

|

|

P1

|

O2

|

19.2

|

5.5

|

18.5

|

1.15

|

|

11.3

|

2.6

|

4.7

|

|||

|

0.78

|

4.8

|

–7.6

|

|||

|

Ar

|

43.4

|

1.6

|

8.0

|

1.31

|

|

|

26.5

|

1.1

|

4.5

|

|||

|

1.51

|

1.7

|

–0.4

|

|||

|

P2

|

O2

|

43.3

|

0.1

|

1.2

|

1.16

|

|

20.4

|

3.7

|

–2.6

|

|||

|

1.75

|

1.9

|

–10.0

|

|||

|

Ar

|

49.81

|

3.1

|

18.5

|

1.08

|

|

|

20.0

|

0.8

|

2.3

|

|||

|

1.53

|

1.8

|

–11.8

|

|||

The thermal properties of polymers P1 and P2 were investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Figs. 8, 9, Tables 5, 6). It was found that the introduction of terminal naphthalene fragments into polysiloxane P1 leads to an increase in the thermal stability up to 305 °С in air and 300 °С in argon. At the same time, P2 show thermal stability similar to that of M2. The mass loss at a relatively low temperature in the case of M1 is obviously associated with the sample evaporation. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that the introduction of naphthalene fragments into the polysiloxanes leads to the loss of crystallization of the latter.

Figure 8. TGA (top) and DSC (bottom) curves for M1 and P1.

Figure 9. TGA (top) and DSC (bottom) curves for M2 and P2.

Table 5. TGA analysis data for polymers M1, M2, P1, and P2

|

Comp.

|

Td5%, °C

|

Residue after decomposition, %

|

||

|

Air

|

Ar

|

Air

|

Ar

|

|

|

M1

|

160

|

158

|

20

|

4

|

|

M2

|

382

|

398

|

17

|

2

|

|

P1

|

305

|

300

|

9

|

0

|

|

P2

|

378

|

379

|

16

|

18

|

| Td5% is the temperature at which a weight loss of 5% was detected. |

Table 6. DSC analysis data for polymers M1, M2, P1, and P2

|

Comp.

|

Tg, °C

|

Tcc, °C

|

DHcc, J/g

|

Tm1, °C

|

DHm1, J/g

|

Tm2, °C

|

DHm2, J/g

|

|

|

M1

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–48.5

|

39.9

|

–33.2

|

5.7

|

|

|

M2

|

–127

|

–90.5

|

16.6

|

–52

|

13.8

|

–43

|

16.9

|

|

|

P1

|

–112

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

|

P2

|

–118

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

| Tg is the glass transition temperature. |

Experimental section

General remarks

Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane, heptamethylcyclotetrasiloxane, hexamethyldisiloxane, tetramethyldisiloxane, and Amberlyst 15 were purchased from ABCR. 1-Allylnaphthalene was prepared by the previously described procedure [39]. Platinum(0)-1,3-divinyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane complex solution (in xylene, Pt-2%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals were used without further purification. Toluene was distilled from CaH2. The 1Н, 13C, and 29Si NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance II spectrometer (400 MHz, Germany). The chemical shifts for the 1Н NMR spectra are reported relative to chloroform (δ = 7.25 ppm). The IR spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu IRTracer-100 IR FTIR spectrometer (Japan). The GPC analyses were performed in toluene (1 mL/min) using a Shimadzu Prominent system equipped with an RID-20A refractive index detector. The GPC columns (Phenogel) were calibrated with polystyrene standards (PSS). The absorption spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-1900 spectrophotometer (Japan). The fluorescence spectra in solution and in the condensed state were measured on a Shimadzu RF-6000 spectrofluorophotometer (Japan). Spectroscopic grade solvents (Aldrich) were used in UV-vis absorption and fluorescence measurements. To measure the optical properties in solution, the quartz cells with an optical path length of 10 mm were used. The optical densities were typically between 0.7 and 0.9 for the absorption measurements and around 0.03–0.09 for the fluorescence measurements (c = 1 μM). The optical properties in the condensed state were measured using films with a thickness of about 200–500 μm. The fluorescence quantum yields were determined using naphthalene as a reference. The fluorescence decay curves were obtained with a Picoquant Fluotime 300 spectrofluorometer. PLS-270 was used as an excitation source (λex = 275 nm). Filter HOYA UV-30 was installed before an entrance slit of the emission monochromator to reduce scattered excitation light. The data fitting was performed using the Easytau2 (Picoquant) software. The TGA studies were performed on a Shimadzu DTG-60H instrument (Japan) using 5 mg samples at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in air or argon. The temperature at which a weight loss of 5% was detected was considered to be the decomposition onset temperature. The DSC measurements were performed on a Mettler-Toledo DSC-3 calorimeter (Switzerland) at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in an argon atmosphere.

Syntheses

Polysiloxane with the end-capped Si–H groups (M1). A mixture of octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (0.160 mol), tetramethyldisiloxane (0.032 mol), and Amberlyst 15 (0.1 g) was stirred at 80 °С for 24 h. After the reaction completion, the resulting mixture was cooled down to room temperature. Amberlyst 15 was filtered off. Then, the filtrate was dried in a vacuum oven (1 mbar) at 100 °С for 6 h. Polymer M1 was obtained as a colorless oil. Yield: 72%. Mn = 2.5 kDa, Mw = 4.1 kDa, PDI = 1.66. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.06 (s, 141H, SiCH3), 0.18 (d, 12H, J = 2.7 Hz, SiCH3), 4.70 (m, 2H, SiH) ppm. 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.7, 0.9, 1.0 ppm. 29Si NMR (79 MHz, CDCl3): δ –21.88, –21.76, –19.80, –6.87 ppm. IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 2963, 2905, 2128, 1413, 1261, 1093, 1023, 914, 864, 798, 704, 660.

Polysiloxane with the end-capped naphthalene fragments (P1). A solution of 1-allylnaphthalene (1.630 mmol), polymer M1 (0.545 mmol), and Karstedt's catalyst (0.03 mL, 0.3 mol % [Pt]) in dry toluene (10 mL) was stirred at room temperature in an argon atmosphere for 24 h. After the reaction completion, the solvent was removed under vacuum. Polymer P1 was purified by GPC. Yield: 87%. Mn = 3.6 kDa, Mw = 5 kDa, PDI = 1.39. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.08 (s, 151H, SiCH3), 0.71 (m, 2H, SiCH2), 1.80 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.09 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.31 (d, 2H, Ar), 7.40 (t, 2H, Ar), 7.48 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.72 (d, 2H, Ar), 7.85 (d, 2H, Ar), 8.04 (d, 2H, Ar) ppm. 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ –0.65, 0.20, 0.32, 17.80, 23.90, 36.01, 123.06, 124.48, 124.65, 124.76, 125.11, 125.56, 127.85, 133.02, 137.95 ppm. 29Si NMR (79 MHz, CDCl3): δ –21.91, 7.36 ppm. IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3096, 3062, 3048, 2962, 2905, 2873, 2797, 2662, 2499, 1943, 1597, 1511, 1445, 1412, 1400, 1260, 1093, 1020, 863, 796, 703, 662, 504.

Polysiloxane with the side-chain distributed naphthalene fragments (P2). A solution of 1-allylnaphthalene (0.66 mmol), polymer M2 (0.33 mol), and Karstedt's catalyst (0.03 mL, 0.3 mol % [Pt]) in dry toluene (10 mL) was stirred at room temperature in an argon atmosphere for 24 h. After the reaction completion, the solvent was removed under vacuum. Polymer P1 was purified by GPC. Yield: 92%. Mn = 44.2 kDa, Mw = 76.7 kDa, PDI = 1.73. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.06 (s, 176H, SiCH3), 0.66 (m, 2H, SiCH2), 1.80 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.06 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.29 (d, 2H, Ar), 7.36 (t, 2H, Ar), 7.45 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.68 (d, 2H, Ar), 7.82 (d, 2H, Ar), 8.02 (d, 2H, Ar) ppm. 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, 18.0, 24.5, 36.8, 124.1, 125.5, 125.6, 125.7, 126.1, 126.5, 128.8 ppm. 29Si NMR (79 MHz, CDCl3): δ –50.01, –21.91 ppm. IR (KBr,ν/cm–1): 3097, 3063, 3048, 2963, 2906, 2799, 2663, 2500, 2052, 1944, 1598, 1512, 1446, 1412, 1400, 1261, 1095, 1020, 864, 799, 703, 687, 662, 499.

Conclusions

In summary, the method for obtaining new naphthalene end-capped and side-chain modified polydimethylsiloxanes was described. The investigation of the optical properties using electron absorption and steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy revealed that both of the resulting polymers exhibit excimer fluorescence in the condensed state. The thermal properties were studied by thermogravimetric analysis and differential scanning calorimetry. It was shown that the introduction of terminal naphthalene fragments into the polysiloxane leads to an increase in the thermal stability up to 305 °С in air and 300 °С in argon. The introduction of the naphthalene fragments into the polysiloxanes leads to the loss of crystallization of the latter.

Acknowledgements

The spectroscopic studies were performed with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement no. 075-00277-24-00) using the equipment of the Center for Molecular Composition Studies of INEOS RAS. The fluorescence lifetime measurements were performed using the equipment of the Shared Research Center "Structural diagnostics of materials" of FSRC "Crystallography and Photonics" RAS within the state assignment FSRC "Crystallography and Photonics" RAS.

References

- P. F. Jones, M. Nicol, J. Chem. Phys., 1965, 43, 3759–3760. DOI: 10.1063/1.1696547

- P. F. Jones, M. Nicol, J. Chem. Phys., 1968, 48, 5457–5464. DOI: 10.1063/1.1668239

- C. Agarwal, E. Prasad, RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 8015–8022. DOI: 10.1039/c3ra45510f

- X. Xiang, D. Wang, Y. Guo, W. Liu, W. Qin, Photochem. Photobiol. Sci., 2013, 12, 1232–1241. DOI: 10.1039/c3pp00007a

- P. F. Jones, M. Nicol, J. Chem. Phys., 1968, 48, 5440–5447. DOI: 10.1063/1.1668237

- M. Nicol, M. Vernon, J. T. Woo, J. Chem. Phys., 1975, 63, 1992–1999. DOI: 10.1063/1.431535

- K. Uchida, M. Tanaka, M. Tomura, J. Lumin., 1979, 20, 409–414. DOI: 10.1016/0022-2313(79)90012-7

- J. B. Birks, J. B. Aladekomo, Spectrochim. Acta, 1964, 20, 15–21. DOI: 10.1016/0371-1951(64)80196-X

- B. Narayan, K. Nagura, T. Takaya, K. Iwata, A. Shinohara, H. Shinmori, H. Wang, Q. Li, X. Sun, H. Li, S. Ishihara, T. Nakanishi, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2018, 20, 2970–2975. DOI: 10.1039/C7CP05584F

- L. Mohanambe, S. Vasudevan, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2005, 109, 22523–22529. DOI: 10.1021/jp053925f

- M. Vera, H. Santacruz Ortega, M. Inoue, L. Machi, Supramol. Chem., 2019, 31, 336–348. DOI: 10.1080/10610278.2019.1588971

- S. Adhikari, S. Mandal, A. Ghosh, S. Guria, D. Das, Dalton Trans., 2015, 44, 14388–14393. DOI: 10.1039/C5DT02146D

- Y. Itoh, M. Inoue, Eur. Polym. J., 2000, 36, 2605–2610. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-3057(00)00052-5

- H. Itagaki, K. Sugiura, H. Sato, Macromol. Chem. Phys., 2001, 202, 90–96. DOI: 10.1002/1521-3935(20010101)202:1<90::AID-MACP90>3.0.CO;2-H

- L. Cheng, G. Wang, M. A. Winnik, Polymer, 1990, 31, 1611–1614. DOI: 10.1016/0032-3861(90)90176-Y

- F. Mendicuti, B. Patel, W. L. Mattice, Polymer, 1990, 31, 453–457. DOI: 10.1016/0032-3861(90)90384-B

- R. F. Reid, I. Soutar, J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Phys. Ed., 1978, 16, 231–244. DOI: 10.1002/pol.1978.180160205

- D. Phillips, A. J. Roberts, I. Soutar, Polymer, 1981, 22, 293–298. DOI: 10.1016/0032-3861(81)90038-0

- R. F. Reid, I. Soutar, J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Phys. Ed., 1980, 18, 457–467. DOI: 10.1002/pol.1980.180180306

- R. A. Anderson, R. F. Reid, I. Soutar, Eur. Polym. J., 1979, 15, 925–929. DOI: 10.1016/0014-3057(79)90230-1

- S. Nishimoto, K. Yamamoto, T. Kagiya, Macromolecules, 1982, 15, 1180–1185. DOI: 10.1021/ma00232a043

- J. A. Ibemesi, J. B. Kinsinger, M. A. El-Bayoumi, J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Chem. Ed., 1980, 18, 879–890. DOI: 10.1002/pol.1980.170180309

- S. Ahmad, A. P. Gupta, E. Sharmin, M. Alam, S. K. Pandey, Prog. Org. Coat., 2005, 54, 248–255. DOI: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.06.013

- J. Hong, J. Lee, D. Jung, S. E. Shim, Thermochim. Acta, 2011, 512, 34–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.tca.2010.08.019

- S. Simmons, M. Shah, J. Mackevich, R. J. Chang, IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag., 1997, 13, 25–32. DOI: 10.1109/57.620515

- F. de Buyl, Int. J. Adhes. Adhes., 2001, 21, 411–422. DOI: 10.1016/S0143-7496(01)00018-5

- S. C. Surita, B. Tansel, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., 2014, 102, 79–83. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.01.012

- C. E. Brunchi, A. Filimon, M. Cazacu, S. Ioan, High Perform. Polym., 2009, 21, 31–47. DOI: 10.1177/0954008308088737

- J. Curtis, A. Colas, in: Biomaterials Science (Third Ed.), B. D. Ratner, A. S. Hoffman, F. J. Schoen, J. E. Lemons, (Eds.), Acad. Press, 2013, ch. II.5.18, pp. 1106–1116. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-08-087780-8.00107-8

- B. D. Ratner, A. S. Hoffman, in: Biomaterials Science (Third Ed.), B. D. Ratner, A. S. Hoffman, F. J. Schoen, J. E. Lemons, (Eds.), Acad. Press, 2013, ch. I.2.10, pp. 241–247. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-08-087780-8.00025-5

- T. R. Neu, H. C. Van der Mei, H. J. Busscher, F. Dijk, G. J. Verkerke, Biomaterials, 1993, 14, 459–464. DOI: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90149-V

- M. J. Whitford, Biomaterials, 1984, 5, 298–300. DOI: 10.1016/0142-9612(84)90077-2

- B. Ustbas, D. Kilic, A. Bozkurt, M. E. Aribal, O. Akbulut, Ultrasonics, 2018, 88, 9–15. DOI: 10.1016/j.ultras.2018.03.001

- A. S. Belova, A. G. Khchoyan, T. M. Il'ina, Y. N. Kononevich, D. S. Ionov, V. A. Sazhnikov, D. A. Khanin, G. G. Nikiforova, V. G. Vasil'ev, A. M. Muzafarov, Polymers, 2022, 14, 5075. DOI: 10.3390/polym14235075

- A. S. Belova, Y. N. Kononevich, D. S. Ionov, V. A. Sazhnikov, A. D. Volodin, A. A. Korlyukov, P. V. Dorovatovskii, M. V. Alfimov, A. M. Muzafarov, Dyes Pigm., 2023, 208, 110852. DOI: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110852

- Y. N. Kononevich, A. S. Belova, V. A. Sazhnikov, A. A. Safonov, D. S. Ionov, A. D. Volodin, A. A. Korlyukov, A. M. Muzafarov, Tetrahedron Lett., 2020, 61, 152176. DOI: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.152176

- T. Karatsu, T. Shibata, A. Nishigaki, A. Kitamura, Y. Hatanaka, Y. Nishimura, S.-i. Sato, I. Yamazaki, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2003, 107, 12184–12191. DOI: 10.1021/jp0355760

- K. Imai, S. Hatano, A. Kimoto, J. Abe, Y. Tamai, N. Nemoto, Tetrahedron, 2010, 66, 8012–8017. DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.08.010

- A. S. Belova, Yu. N. Kononevich, V. A. Sazhnikov, A. A. Safonov, D. S. Ionov, A. A. Anisimov, O. I. Shchegolikhina, M. V. Alfimov, A. M. Muzafarov, Tetrahedron, 2021, 93, 132287. DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2021.132287

- M. Laird, C. Carcel, M. Unno, J. R. Bartlett, M. Wong Chi Man, Molecules, 2022, 27, 7680. DOI: 10.3390/molecules27227680

- S.-i. Kondo, S. Abe, H. Katagiri, Dyes Pigm., 2023, 217, 111394. DOI: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2023.111394

- H. Narikiyo, M. Gon, K. Tanaka, Y. Chujo, Mater. Chem. Front., 2018, 2, 1449–1455. DOI: 10.1039/C8QM00181B

- J. Sun, H. Tang, J. Jiang, X. Zhou, P. Xie, R. Zhang, P.-F. Fu, J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem., 2003, 41, 636–644. DOI: 10.1002/pola.10607

- S. O. Hwang, A. S. Lee, J. Y. Lee, S.-H. Park, K. I. Jung, H. W. Jung, J.-H. Lee, Prog. Org. Coat., 2018, 121, 105–111. DOI: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2018.04.022

- M. Briesenick, M. Gallei, G. Kickelbick, Macromolecules, 2022, 55, 4675–4691. DOI: 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00265

- E. E. Kim, Y. N. Kononevich, Y. S. Dyuzhikova, D. S. Ionov, D. A. Khanin, G. G. Nikiforova, O. I. Shchegolikhina, V. G. Vasil'ev, A. M. Muzafarov, Polymers, 2022, 14, 2554. DOI: 10.3390/polym14132554

- F. Mendicuti, B. Patel, W. L. Mattice, Polymer, 1990, 31, 453–457. DOI: 10.1016/0032-3861(90)90384-B