2023 Volume 6 Issue 1

|

INEOS OPEN, 2023, 6 (1), 21–26 Journal of Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds Download PDF |

|

Hybrid Silver-Containing Nanocomposites Based on Bacterial Cellulose:

New Methods for Synthesis, Structure and Properties

a Nesmeyanov Institutre of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Vavilova 28, str. 1, Moscow, 119334 Russia

b Gause Institute of New Antibiotics, ul. Bol'shaya Pirogovskaya 11, Moscow, 119021 Russia

c Dukhov Automatics Research Institute, ul. Sushchevskaya 22, Moscow, 127030 Russia

Corresponding author: A. Yu. Vasil'kov, e-mail: alexandervasilkov@yandex.ru

Received 6 September 2023; accepted 9 November 2023

Abstract

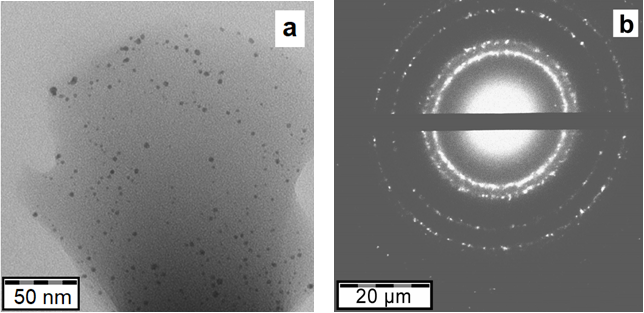

New silver-containing hybrid materials based on bacterial cellulose were obtained by a technological approach that combines three techniques: the formation of bacterial cellulose under static conditions, the modification of its surface by plasma treatment, and the introduction of silver nanoparticles obtained by metal vapor synthesis. The plasma treatment is found to significantly change the morphology and composition of the polymer surface. The oxidation state of silver is shown to correspond to Ag0. The resulting systems exhibit antimicrobial activity.

Key words: bacterial cellulose, plasma treatment, metal vapor synthesis, antimicrobial activity, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, silver nanoparticles.

Introduction

In the field of wound care dressings, many efforts are focused on the creation of a biocompatible material that would promote accelerated wound healing [1].

Bacterial cellulose (BC) is a biopolymer that features nanofibrillar microporous structure, high mechanical strength, and biocompatibility [2–5]. BC on its own does not display antimicrobial or antifungal effects. To impart antibacterial properties to BC, the material is modified with antibiotics [6] and/or Ag, Cu, ZnO, TiO2, Fe, and Au nanoparticles [7–11]. The use of metal nanoparticles (NPs) is more preferable, since pathogenic organisms rapidly develop resistance to antibiotics, which poses a huge problem for modern medicine [12]. The modification of BC with nanoparticles of biologically active metals expands its application scope for various biomedical purposes [13].

Silver-containing composites based on bacterial cellulose are of particular interest as materials for medical purposes [14–17]. There are various methods for the production of metal nanoparticles and modification of bacterial cellulose with them [18, 19]. The synthesis of nanoparticles is performed, as a rule, by chemical reduction of metal salts [20]. The reduction of metal salts using chemical reagents [21–23] or electromagnetic radiation [24] has a number of serious drawbacks: prolonged synthetic procedure, the presence of a considerable amount of impurities, and the complicated control of the metal reduction degree [25, 26].

One of the promising routes for obtaining biologically active metal nanoparticles is metal vapor synthesis (MVS). This method is widely used for the production of new biomedical hybrid metal-containing polymers [27, 28]. The MVS is based on simultaneous evaporation and condensation of metal and organic ligand vapors on the reactor walls cooled with liquid nitrogen under vacuum (10–2 Pa). The advantage of this method is the absence of by-products in metal nanoparticles, which is particularly important for the purity of biomedical materials [29].

The stabilization of metal nanoparticles occurs, as a rule, owing to the partial interaction with hydroxy groups, being present in the composition of BC, as well as the physical sorption of nanoparticles in the porous structure of cellulose. In some cases, this is not enough for effective chemisorption of noble metal nanoparticles, which exhibit biological activity and are interesting for the application for medical purposes, on the surface of BC [30, 31]. Chemical [32, 33] or plasma [34, 35] treatment of BC enables the modification of the polysaccharide surface. Depending on the composition of the working gas and flow parameters, plasma treatment can cause erosion of the polysaccharide surface and/or its controlled oxidation [36–38]. Varying the parameters during plasma processing of polymers allows one to change the composition of the surface and its roughness, as well as other properties of the material. This leads to the formation of new functional groups that can effectively stabilize metal nanoparticles [39].

In this work, new silver-containing hybrid materials based on bacterial cellulose were obtained for the first time using a technological approach that combines three techniques: the formation of bacterial cellulose under static conditions, the modification of its surface by plasma treatment, and the introduction of silver nanoparticles obtained by metal vapor synthesis.

Results and discussion

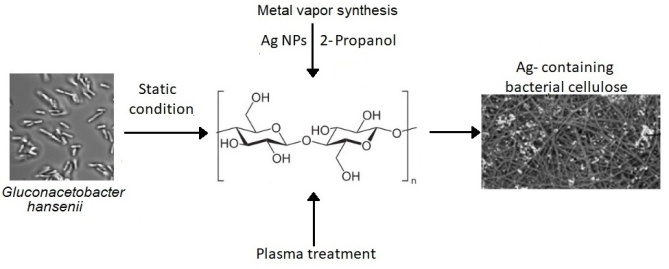

To obtain bacterial cellulose, the strain Gluconacetobacter hanseni GH-1/2008 was used (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Biosynthesis of bacterial cellulose films by Gluconacetobacter hansenii GH-1/2008.

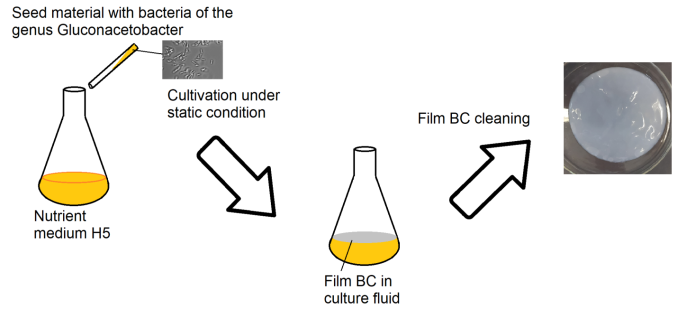

The cultivation afforded BC films which were then freeze-dried. The resulting material was treated with cold low-pressure plasma in air (oxygen–nitrogen) atmosphere. After plasma treatment, bacterial cellulose (BCP) was modified with an organosol of Ag NPs in isopropanol to form silver-containing BCP (BCP-Ag) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Scheme for the production of silver-containing bacterial cellulose using plasma treatment and metal vapor synthesis: (1) electrodes, (2) bacterial cellulose, (3) plasma discharge, (4) radio-frequency alternating current generator, (5) vacuum pump, (6) vacuum line, (7) product output line, (8) flask with an organic solvent, (9) resistive evaporator, (10) cryomatrix, (11) magnetic stirrer.

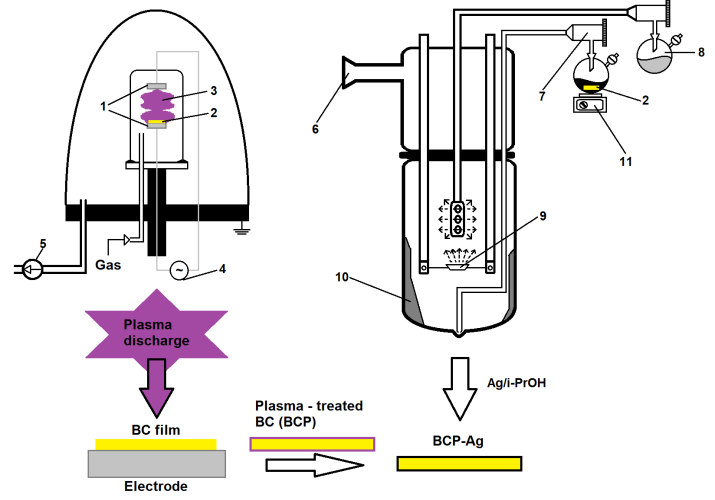

The silver organosol in isopropanol obtained by the MVS was studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The analysis of micrographs and electron diffraction patterns showed that Ag particles are spherical and polydisperse, the average NP size is 2.5 nm (see Fig. S1 in the Electronic supplementary information (ESI)) and the electron diffraction pattern corresponds to the Ag0 oxidation state (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. TEM micrograph (a) and electron diffraction pattern of Ag nanoparticles (b) for the silver–isopropanol system.

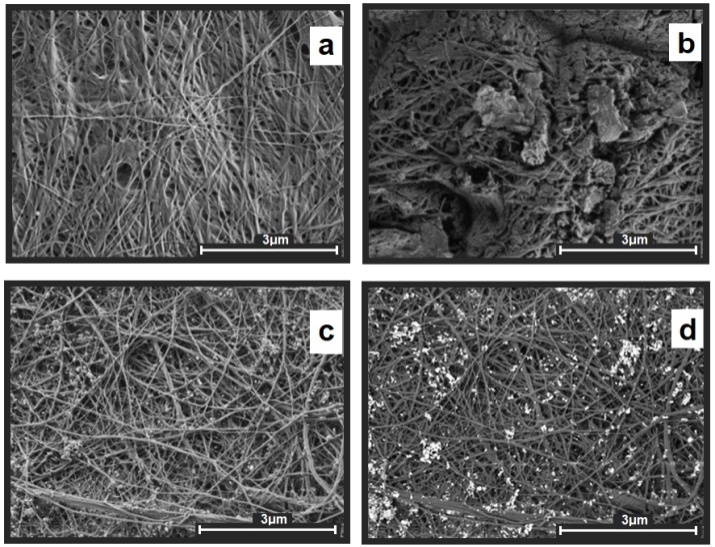

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies revealed that plasma treatment led to partial destruction of the BCP fibrous structure and an increase in the surface roughness (Figs. 4a,b). The modification of BCP with the Ag NPs organosol did not affect the morphology of the polymer surface. The silver nanoparticles in BCP-Ag are uniformly distributed over the surface of the polymer (Figs. 4c,d).

Figure 4. SEM micrographs: BC (a), BCP (b), dark-field (c) and bright-field (d) BCP-Ag images.

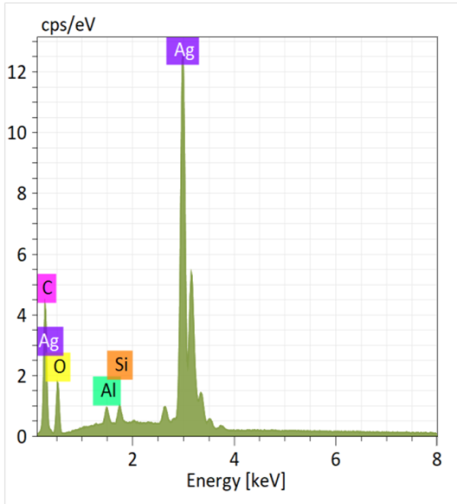

The analysis of the BCP-Ag composite by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) showed that there are carbon, silver, and oxygen on the surface of the polymer, as well as some minor impurities, such as aluminum and silicon (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. EDX pattern of the BCP-Ag nanocomposite.

The analysis of the BC surface modified by plasma treatment and silver nanoparticles was performed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

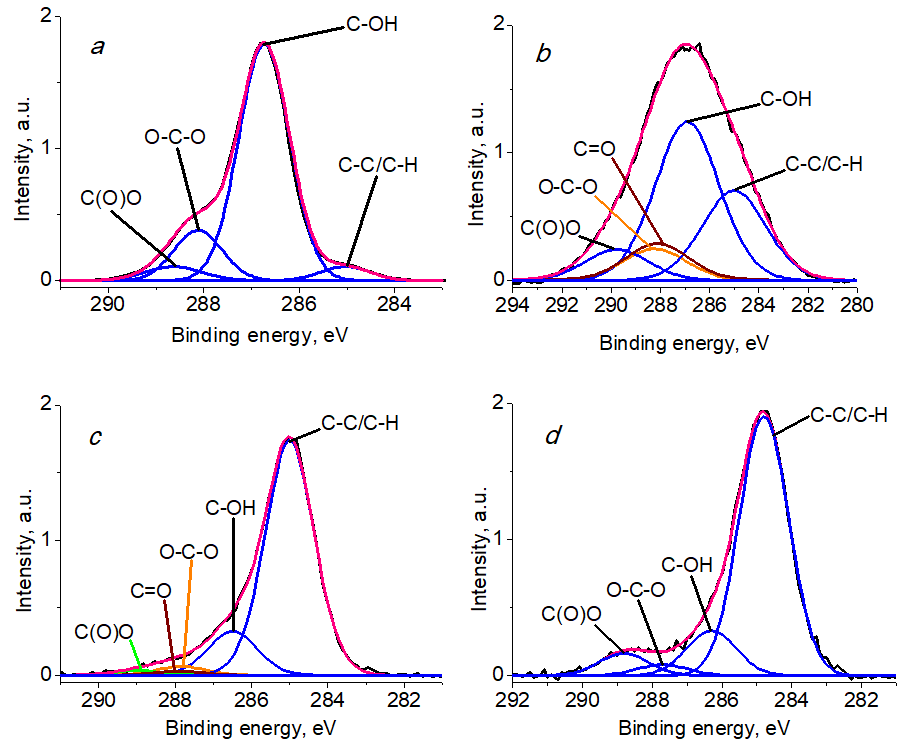

The typical structure of C 1s spectra for cellulose represents 4 states: C–C/C–H, C–OH, O–C–O, and C(O)O with binding energies of 285.0, 286.7, 288.1, and 289.4 eV, respectively [40–45].

Figure 6 shows the C 1s photoelectron spectra of BC, BCP, BCP-Ag, and Ag nanoparticles. The relative intensities of the different groups and the characteristics of the photoelectron peaks are presented in Table 1. The analysis of the results showed that the ratio of the peaks of the C–OH and O–C–O groups characteristic of cellulose retain a 5:1 ratio that answers to the structural formula of cellulose [46].

Figure 6. C 1s photoelectron spectra of BC (a), BCP (b), BCP-Ag (c), and Ag NPs (d).

Table 1. Characteristics of the C 1s photoelectron spectra: binding energies (Eb), the Gaussian widths (FWHM), and relative intensities (Irel) of the photoelectron peaks related to different chemical groups

|

Sample

|

|

C–C/C–H

|

C–OH

|

O–C–O

|

C=O

|

C(O)O

|

|

BC

|

Eb, eV

|

285.03

|

286.73

|

288.11

|

|

288.63

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

1.01

|

1.03

|

1.03

|

|

1.20

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

5

|

75

|

15

|

|

5

|

|

|

BCP

|

Eb, eV

|

285.0

|

286.91

|

288.24

|

288.12

|

289.77

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

3.06

|

3.06

|

3.06

|

3.06

|

3.06

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

26

|

45

|

9

|

11

|

9

|

|

|

BCP-Ag

|

Eb, eV

|

285.0

|

286.49

|

287.82

|

287.90

|

288.99

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

79

|

15

|

3

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

|

|

Ag NPs

|

Eb, eV

|

285.0

|

286.5

|

288.0

|

|

290.1

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

1.43

|

1.43

|

1.43

|

|

1.45

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

77

|

13

|

3

|

|

7

|

The analysis of the C 1s spectra showed an increased content of C–C/C–H bonds and C(O)O groups in BCP (Table 1), which indicates partial degradation of the material caused by plasma treatment [47, 48]. The C 1s spectrum of the BCP sample showed in addition the signal of a C=O group, the intensity of which decreases in the BCP-Ag sample, which is apparently caused by the interaction of this and other oxygen-containing polymer groups with silver nanoparticles and a change in the surface composition. A broadening of the peaks was recorded for the BCP sample, which may be due to differential charging. The modification of BCP with Ag nanoparticles led to an increase in the content of the C–C/C–H groups compared to BCP, which is due to the presence of a carbon shell on the metal surface formed during the synthesis of Ag NPs.

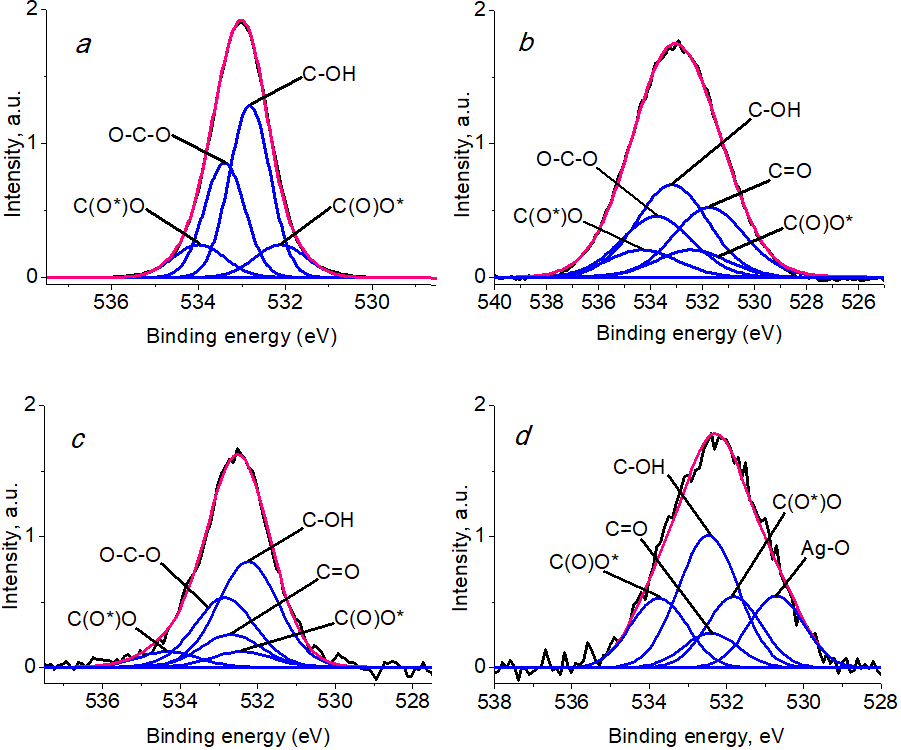

The O 1s spectrum of cellulose exhibited two peaks with binding energies of 532.9 eV and 533.5 eV and relative intensities of 60 and 40%, respectively, which can be attributed to C–OH and O–C–O bonds [46]. A literature survey revealed that the spectra of carboxy groups are described as two peaks of equal intensity with an energy difference of 0.8–1.9 eV [46].

The O 1s spectrum of BC (Fig. 7a) is described by four peaks with binding energies of 532.10, 532.82, 533.40, and 534.0 eV, which refer to the C(O*)O, C–OH, O–C–O, and C(O)O* groups, respectively. The O 1s spectrum of oxidized BCP and BCP modified with Ag nanoparticles revealed the presence of a C=O group (Figs. 7b,c).

Figure 7. O 1s photoelectron spectra of BC (a), BCP (b), BCP-Ag (c), and Ag NPs (d).

The intensity of the C–OH/O–C–O groups, which decreases during the oxidation of BC, increases after the modification of BC with silver nanoparticles (Table 2). This may be due to both the interaction of oxygen-containing groups with silver nanoparticles and other processes (for example, epoxidation and other reactions) that are characteristic of Ag and can occur on the highly active surface of metal particles.

Table 2. Characteristics of the O 1s photoelectron spectra: binding energies (Eb), the Gaussian widths (FWHM), and relative intensities (Irel) of the photoelectron peaks related to different chemical groups

|

Sample

|

|

Ag–O

|

C=O

|

C(O*)O

|

C–OH

|

O–C–O

|

C(O)O*

|

|

BC

|

Eb, eV

|

|

|

532.10

|

532.82

|

533.40

|

534.0

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

|

|

1.4

|

1.1

|

1.1

|

1.4

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

|

|

11

|

47

|

31

|

11

|

|

|

BCP

|

Eb, eV

|

|

531.74

|

532.43

|

533.17

|

533.77

|

534.33

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

|

3.24

|

3.24

|

3.24

|

3.24

|

3.24

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

|

26

|

10

|

33

|

21

|

10

|

|

|

BCP-Ag

|

Eb, eV

|

|

532.68

|

532.4

|

532.25

|

532.85

|

534.30

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

|

1.83

|

1.83

|

1.83

|

1.83

|

1.83

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

|

14

|

6.5

|

44

|

29

|

6.5

|

|

|

Ag NPs

|

Eb, eV

|

530.7

|

532.4

|

531.8

|

532.5

|

|

533.8

|

|

FWHM, eV

|

1.42

|

1.42

|

1.42

|

1.55

|

|

1.55

|

|

|

Irel, %

|

18

|

9

|

18

|

37

|

|

18

|

The O 1s spectrum of BCP, as well as the C 1s spectrum, contains slightly broadened peaks, which can be caused not only by differential charging, but also by the inability to completely compensate for surface charging due to the massiveness/thickness of the sample.

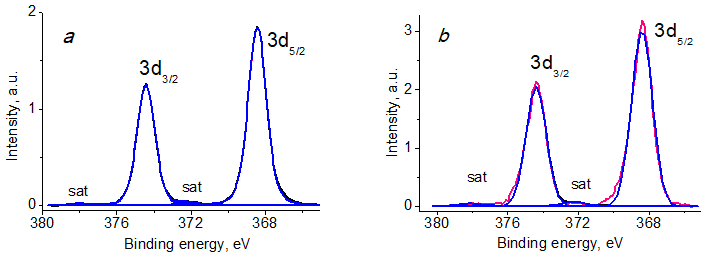

Figure 8 shows the photoelectron spectra of Ag 3d BCP-Ag and Ag NPs, in which the Ag 3d5/2 peaks correspond to the values of 368.42 and 368.41 eV, respectively. Table 3 presents their characteristics. The difference in the parameters for the tested samples relative to the standard characteristic for metallic silver of 368.21 eV (0.2 eV) is caused by the size effect.

Figure 8. Ag 3d photoelectron spectra of BCP-Ag (a) and Ag NPs (b).

Table 3. Characteristics of the Ag 3d photoelectron spectra: binding energy (Eb) and spin-orbit splitting (ΔEAg)

|

Sample

|

Eb

|

ΔEAg

|

Eb

|

Oxidation state

|

||

|

Ag 3d5/2, eV

|

Ag 3d3/2, eV

|

Ag 3d3/2 - Ag 3d5/2,

eV |

Ag 3d5/2 satellite, eV

|

Ag 3d3/2

satellite, eV |

||

|

BCP-Ag

|

368.42

|

374.43

|

6.01

|

372.28

|

378.06

|

Ag0

|

|

Ag NPs

|

368.41

|

374.40

|

5.99

|

372.26

|

378.06

|

Ag0

|

The Ag 3d spectrum of BCP-Ag shows a characteristic doublet with spin splitting of 6 eV and satellites at a distance of 3.9 eV from the main peaks. The binding energy of Ag 3d5/2 was 368.42 eV, which indicates the presence of metallic silver [49, 50].

The antimicrobial activity of BC, BCP and BCP-Ag was evaluated using the disk diffusion method. It was found that bacterial cellulose treated with plasma did not exhibit antimicrobial activity against the strains explored. The BCP-Ag nanocomposite displayed strong antibiotic activity against gram-negative bacteria E. coli and fungi P. brevicompactum, P. chrysogenum, C. albicans, and A. fumigatus. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Antimicrobial activity of BC, BCP, and BCP-Ag

|

Sample

|

Inhibition zone, mm

|

|||||

|

E.coli АТСС 25922

|

P.brev. VKM F-4481

|

P.сhr. VKM F-4499

|

C.alb. ATCC 2091

|

A.fum. KPB F-37

|

||

|

BC

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

BCP

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

BCP-Ag

|

13.0 ± 0.7

|

11.0 ± 0.4

|

10.0 ± 0.5

|

12.0 ± 0.5

|

15.0 ± 0.8

|

|

|

Amoxiclav 40 μg/g

|

n/d

|

10.0 ± 0.4

|

10.0 ± 0.7

|

23.0 ± 0.9

|

12.0 ± 0.4

|

|

| n/d—not determined. |

Experimental section

Bacterial cellulose was obtained by cultivating the producing strain Gluconacetobacter hansenii GH-1/2008, which was carried out for 7 days at 28 °C under static conditions in the modified Hestrin S. and M. Schramm medium: glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) 40 g/L, yeast extract (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) 5 g/L, Na2HPO4 (AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) 2.7 g/L, K2HPO4 (AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) 2 g/L, (NH4)2SO4 (Sigma-Aldrich RTC, Inc., Laramie, WY, USA) 3 g/L, citric acid monohydrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) 1.15 g/L. The culture medium was sterilized in an autoclave (All American 50×, Wisconsin Aluminum, Manitowoc, WI, USA) at 120 °C for 0.5 h. Inoculum (5 mL) and EtOH (1 mL) were added to the flasks with the medium at 22 °C. The process was carried out in a laminar flow hood (NEOTERIC BMB-II-Laminar-C-0.9b Industrial Group "Laborator", St. Petersburg, Russia). To obtain BC, the Ehrlenmeyer flasks with a volume of 750 mL with 200 mL of medium were used that were placed in a thermostat (RF 115, Binder GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany).

The polymer was purified from the culture medium and the producing strain using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), sequentially adding deoxyribonuclease I (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The procedure was repeated in 24 h. The resulting BC was rinsed with distilled water until the neutral pH value.

The plasma treatment of BC films was performed with a modified high-voltage converter of a VUP-5 vacuum station (OOO SELMI, Sumy, Ukraine). The polymer modification was carried out in low-temperature alternating plasma at a working gas pressure of 10 Pa, exposure time of 300 s, discharge power of 100 W with a frequency of 15 kHz and discharge voltage of 3 kV. The exposure time was chosen based on the previous results [51]. The composition of the active gas corresponded to an atmospheric one.

The MVS unit and the experimental technique are described in detail elsewhere [14, 52–55]. Isopropanol (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland, 99.8%) was dried and distilled over zeolites under purified argon. Prior to the synthesis, the solvent was degassed by alternating freeze-thaw cycles. Silver (99.99%) was evaporated from a tantalum boat. In a typical experiment, 120 mL of the organic reagent and 0.2 g of the metal were used for synthesis. The co-condensation of the metal and organic ligand vapors was carried out in a stationary quartz reactor with a volume of 5 L, cooled to 77 K. When the evaporation of the metal was completed, the supply of the organic reagent was stopped. The cooling was removed and the co-condensate was heated until melting. As a result, an organosol was formed at the bottom of the reactor, which, through a siphon system, entered an evacuated flask with BCP, which was mounted on porous cylindrical stainless steel frames. The modification was carried out under vigorous stirring in an argon atmosphere for 20 min. Then the excess organosol was removed and the BCP-Ag product was dried to constant mass at 60 °C under vacuum (10 Pa).

The TEM images were obtained on a Zeiss LEO 912AB OMEGA transmission electron microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. A diagram of particle size distribution was calculated based on measurements of 200 particles using SigmaScan Pro software. The distribution was fitted by a Gaussian function using SigmaPlot software (version 11) (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA, USA).

The SEM and energy dispersive analyses were performed on a Hitachi TM4000Plus electron microscope equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (QUANTAX 75, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

The XPS analysis was carried out on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Theta Probe spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using a monochromated Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The spectra were recorded at room temperature and a pressure of ~5×10–8 Pa. The samples were fixed on a titanium holder using a double-sided tape. The energy scale of the spectrometer was calibrated to Au 4f7/2 83.96 eV, Cu 2p3/2 932.62 eV, Ag 3d5/2 368.21 eV. The full and high-resolution spectra were recorded at constant transmission energies of 300 and 100 eV and with the steps of 1 and 0.1 eV, respectively. The effects of electrostatic charge were compensated using an electron neutralizer. The binding energy scales were assigned to the C–OH component in the C 1s spectra at 286.73 eV for the cellulose samples [56] and at 285 eV to the C–C/C–H bonds.

The antimicrobial activity of BCP-Ag was assessed by the agar diffusion method. The inhibition zones were measured manually using a digital caliper. The analyses were performed in triplicate. Amoxiclav 40 μg (Pasteur Research Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia) was used as a positive control. The antibacterial activity was evaluated using a test strain of gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli ATCC 25922. The antifungal activity was assessed using the strains of opportunistic microscopic fungi Penicillium brevicompactum VKM F-4481, Penicillium chrysogenum VKM F-4499, Candida albicans ATCC 2091, and Aspergillus fumigatus KPB F-37 from the collection of the Gause Institute of New Antibiotics [57]. The test culture of E. coli ATCC 25922 was grown on LB (tryptone soy agar). The fungal test strains were grown on PDA (potato dextrose agar).

Conclusions

New silver-containing hybrid materials based on bacterial cellulose were obtained using a combination of three methods: the formation of bacterial cellulose under static conditions, the modification of its surface by plasma treatment, and the introduction of silver nanoparticles obtained by metal vapor synthesis.

It was established that plasma treatment of bacterial cellulose and its subsequent modification with silver nanoparticles significantly change the morphology and composition of the polymer surface. Silver in the material is found to be in the zero oxidation state.

It was demonstrated that silver-containing plasma-treated bacterial cellulose has antimicrobial activity and may be promising in the creation of wound dressings and other materials for medical use.

Acknowledgements

The work was performed with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement no. 075-03-2023-642) using the equipment of the Center for Molecular composition Studies of INEOS RAS.

Electronic supplementary information

Diagram of the size distribution of Ag NPs. For ESI, see DOI: 10.32931/io2302a

References

- M. Farahani, A. Shafiee, Adv. Healthcare Mater., 2021, 10, 2100477. DOI: 10.1002/adhm.202100477

- C. Zhong, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., 2020, 8, 605374. DOI: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.605374

- J. Wang, J. Tavakoli, Y. Tang, Carbohydr. Polym., 2019, 219, 63–76. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.05.008

- B. V. Mohite, S. V. Patil, Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem., 2014, 61, 101–110. DOI: 10.1002/bab.1148

- R. Curvello, V. S. Raghuwanshi, G. Garnier, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 2019, 267, 47–61. DOI: 10.1016/j.cis.2019.03.002

- G.-M. Lemnaru (Popa), R. D. Truşcă, C.-I. Ilie, R. E. Țiplea, D. Ficai, O. Oprea, A. Stoica-Guzun, A. Ficai, L.-M. Dițu, Molecules, 2020, 25, 4069. DOI: 10.3390/molecules25184069

- T. I. Gromovykh, A. Yu. Vasil'kov, V. S. Sadykova, N. B. Feldman, A. G. Demchenko, A. V. Lyundup, I. E. Butenko, S. V. Lutsenko, Int. J. Nanotechnol., 2019, 16, 408–420. DOI: 10.1504/IJNT.2019.106615

- M. Wasim, M. R. Khan, M. Mushtaq, A. Naeem, M. Han, Q. Wei, Coatings, 2020, 10, 364. DOI: 10.3390/coatings10040364

- A. Khalid, R. Khan, M. Ul-Islam, T. Khan, F. Wahid, Carbohydr. Polym., 2017, 164, 214–221. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.01.061

- S. Farag, A. Amr, A. El-Shafei, M. S. Asker, H. M. Ibrahim, Cellulose, 2021, 28, 7619–7632. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-021-04011-5

- A. A. Voronova, A. V. Naumkin, A. Yu. Vasil'kov, INEOS OPEN, 2022, 5, 79–84. DOI: 10.32931/io2215a

- I. A. Rather, B.-C. Kim, V. K. Bajpai, Y.-H. Park, Saudi J. Biol. Sci., 2017, 24, 808–812. DOI: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.01.004

- C.-N. Wu, S.-C. Fuh, S.-P. Lin, Y.-Y. Lin, H.-Y. Chen, J.-M. Liu, K.-C. Cheng, Biomacromolecules, 2018, 19, 544–554. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01660

- M. Azizi-Lalabadi, F. Garavand, S. M. Jafari, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 2021, 293, 102440. DOI: 10.1016/j.cis.2021.102440

- A. I. Nicoara, A. E. Stoica, D.-I. Ene, B. S. Vasile, A. M. Holban, I. A. Neacsu, Materials, 2020, 13, 4793. DOI: 10.3390/ma13214793

- T. Aditya, J. P. Allain, C. Jaramillo, A. M. Restrepo, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2022, 23, 610. DOI: 10.3390/ijms23020610

- A. Vasil'kov, I. Butenko, A. Naumkin, A. Voronova, A. Golub, M. Buzin, E. Shtykova, V. Volkov, V. Sadykova, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2023, 24, 7667. DOI: 10.3390/ijms24087667

- S. Jiji, S. Udhayakumar, K. Maharajan, C. Rose, C. Muralidharan, K. Kadirvelu, Carbohydr. Polym., 2020, 245, 116573. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116573

- S. Khattak, X.-T. Qin, L.-H. Huang, Y.-Y. Xie, S.-R. Jia, C. Zhong, Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2021, 189, 483–493. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.157

- H. A. Reem, E. M. Damra, Int. Nano Lett., 2020, 10, 1–14. DOI: 10.1007/s40089-019-00291-9

- S. Audtarat, P. Hongsachart, T. Dasri, S. Chio-Srichan, S. Soontaranon, W. Wongsinlatam, S. Sompech, Nanocomposites, 2022, 8, 34–46. DOI: 10.1080/20550324.2022.2055375

- A. R. Deshmukh, P. K. Dikshit, B. S. Kim, Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2022, 205, 169–177. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.02.064

- A. F. Sarkandi, M. Montazer, T. Harifi, M. M. Rad, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2021, 138, 49824. DOI: 10.1002/app.49824

- G. Yang, Y. Yao, C. Wang, Mater. Lett., 2017, 209, 11–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.matlet.2017.07.097

- D. Wei, W. Sun, W. Qian, Y. Ye, X. Ma, Carbohydr. Res., 2009, 344, 2375–2382. DOI: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.09.001

- Y.-K. Twu, Y.-W. Chen, C.-M. Shih, Powder Technol., 2008, 185, 251–257. DOI: 10.1016/j.powtec.2007.10.025

- M. S. Rubina, M. A. Pigaleva, I. E. Butenko, A. V. Budnikov, A. V. Naumkin, T. I. Gromovykh, S. V. Lutsenko, A. Yu. Vasil'kov, Dokl. Phys. Chem., 2019, 488, 146–150. DOI: 10.1134/S0012501619100026

- G. Cárdenas-Triviño, N. Linares-Bermudez, L. Vergara-González, G. Cabello-Guzmán, J. Ojeda-Oyarzún, M. Nuñez- Decap, R. Arrué-Muñoz, J. Chil. Chem. Soc., 2022, 67, 5667–5673. DOI: 10.4067/S0717-97072022000405667

- A. Vasil'kov, M. Rubina, A. Naumkin, M. Buzin, P. Dorovatovskii, G. Peters, Y. Zubavichus, Gels, 2021, 7, 82. DOI: 10.3390/gels7030082

- M. P. Illa, C. S. Sharma, M. Khandelwal, J. Mater. Sci., 2019, 54, 12024–12035. DOI: 10.1007/s10853-019-03737-9

- B. Zeng, N. Byrne, Cellulose, 2021, 28, 8333–8342. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-021-04068-2

- M. Khamrai, S. L. Banerjee, S. Paul, A. K. Ghosh, P. Sarkar, P. P. Kundu, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., 2019, 7, 12083–12097. DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01163

- A. G. Morena, M. B. Roncero, S. V. Valenzuela, C. Valls, T. Vidal, F. I. J. Pastor, P. Diaz, J. Martínez, Cellulose, 2019, 26, 8655–8668. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-019-02678-5

- O. Mauger, S. Westphal, S. Klöpzig, A. Krüger-Genge, W. Müller, J. Storsberg, J. Bohrisch, Plasma, 2020, 3, 196–203. DOI: 10.3390/plasma3040015

- J. Correia, K. Mathur, M. Bourham, F. R. Oliveira, R. De Cássia Siqueira Curto Valle, J. A. B. Valle, A.-F. M. Seyam, Cellulose, 2021, 28, 9971–9990. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-021-04143-8

- S. Leal, C. Cristelo, S. Silvestre, E. Fortunato, A. Sousa, A. Alves, D. M. Correia, S. Lanceros-Mendez, M. Gama, Cellulose, 2020, 27, 10733–10746. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-020-03005-z

- M. S. Rubina, A. V. Budnikov, I. V. Elmanovich, I. O. Volkov, A. Yu. Vasil'kov, Mendeleev Commun., 2022, 32, 283–285. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2022.03.044

- W. Bhanthumnavin, P. Wanichapichart, W. Taweepreeda, S. Sirijarukula, B. Paosawatyanyong, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2016, 306, 272–278. DOI: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.06.035

- S. Mathioudaki, B. Barthélémy, S. Detriche, C. Vandenabeele, J. Delhalle, Z. Mekhalif, S. Lucas, ACS Appl. Nano Mater., 2018, 1, 3464–3473. DOI: 10.1021/acsanm.8b00645

- C. N. Flynn, C. P. Byrne, B. J. Meenan, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2013, 233, 108–118. DOI: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2013.04.007

- L. Fras, L.-S. Johansson, P. Stenius, J. Laine, K. Stana-Kleinschek, V. Ribitsch, Colloids Surf., 2005, 260, 101–108. DOI: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2005.01.035

- C. S. R. Freire, A. J. D. Silvestre, C. P. Neto, A. Gandini, P. Fardim, B. Holmbom, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2006, 301, 205–209. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.04.074

- L.-S. Johansson, J. M. Campbell, O. J. Rojas, Surf. Interface Anal., 2020, 52, 1134–1138. DOI: 10.1002/sia.6759

- D. M. Kalaskar, R. V. Ulijn, J. E. Gough, M. R. Alexander, D. J. Scurr, W. W. Sampson, S. J. Eichhorn, Cellulose, 2010, 17, 747–756. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-010-9413-y

- R. A. N. Pertile, F. K. Andrade, C. Alves Jr., M. Gama, Carbohydr. Polym., 2010, 82, 692–698. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.05.037

- G. Beamson, D. Briggs, High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA300 Database, Wiley, New York, 1992.

- M. Andresen, L.-S. Johansson, B. S. Tanem, P. Stenius, Cellulose, 2006, 13, 665–677. DOI: 10.1007/s10570-006-9072-1

- L.-S. Johansson, J. M. Campbell, Surf. Interface Anal., 2004, 36, 1018–1022. DOI: 10.1002/sia.1827

- J. F. Moulder, W. F. Stickle, P. E. Sobol, K. D. Bomben, Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: A Reference Book of Standard Spectra for Identification and Interpretation of XPS Data, J. Chastain, R. C. King (Eds.), Phys. Electron., Eden Prairie, 1992.

- V. K. Kaushik, J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom., 1991, 56, 273–277. DOI: 10.1016/0368-2048(91)85008-H

- A. Vasil'kov, A. Budnikov, T. Gromovykh, M. Pigaleva, V. Sadykova, N. Arkharova, A. Naumkin, Polymers, 2022, 14, 3907. DOI: 10.3390/polym14183907

- A. Vasil'kov, N. Tseomashko, A. Tretyakova, A. Abidova, I. Butenko, A. Pereyaslavtsev, N. Arkharova, V. Volkov, E. Shtykova, Coatings, 2023, 13, 1315. DOI: 10.3390/coatings13081315

- D. Barbaro, L. Di Bari, V. Gandin, C. Marzano, A. Ciaramella, M. Malventi, C. Evangelisti, PLoS One, 2022, 17, e0269603. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269603

- E. Pitzalis, R. Psaro, C. Evangelisti, Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2022, 533, 120782. DOI: 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120782

- M. S. Rubina, E. E. Kamitov, Ya. V. Zubavichus, G. S. Peters, A. V. Naumkin, S. Suzer, A. Yu. Vasil'kov, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2016, 366, 365–371. DOI: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.01.107

- C. Lai, L. Sheng, S. Liao, T. Xi, Z. Zhang, Surf. Interface Anal., 2013, 45, 1673–1679. DOI: 10.1002/sia.5306

- A. E. Kuvarina, Yu. A. Roshka, E. A. Rogozhin, D. A. Nikitin, A. V. Kurakov, V. S. Sadykova, Appl. Biochem. Microbiol., 2022, 58, 243–250. DOI: 10.1134/S0003683822030085