2021 Volume 4 Issue 4

|

INEOS OPEN, 2021, 4 (4), 117–132 Journal of Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds |

|

Optical Chemosensors for Cations Based on 1,8-Naphthalimide Derivatives

Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Vavilova 28, Moscow, 119991 Russia

Corresponding author: M. A. Pavlova, e-mail: marina_zr@mail.ru

Received 31 March 2021; accepted 13 August 2021

Abstract

This review presents the examples of fluorescent sensors for metal cations based on a 1,8-naphthalimide optical platform and covers the main advances in this field for the last decade. The mechanisms of the generation of an optical signal are discussed in detail. Special attention is given to the authors' own works.

Key words: 1,8-naphthalimide, fluorescent sensor, cation detection, electron transfer, energy transfer.

1. Introduction

The qualitative and quantitative recognition of cations in solution is one of the pressing challenges for ecologists, medicinal and biological chemists [1]. Close attention is drawn to the development of colorimetric and fluorescent sensing systems since the current optical spectroscopic techniques enable highly sensitive analysis in a rapid and relatively simple manner [1–3]. The present review describes the examples of optical chemosensors for metal cations reported for the last decade that utilize the derivatives of naphthalic acid imide (1,8-naphthalimide) as a signal fragment.

The 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives amount to one of the main types of organic luminophores and are of great practical importance. They are used as fluorescent dyes [4, 5], electroluminescent materials [6, 7], anticancer agents [8], and fluorescent markers in biological studies [9–11]. Of particular note is the creation of naphthalimide-based fluorescent chemosensors for metal cations, anions, and neutral molecules [12–16]. Such interest stems from their relative synthetic availability, efficient luminescence in organic solvents, and high sensitivity of the optical properties of resulting chromophores to the nature of substituents in the molecule and microenvironment [17, 18]. This review will mainly focus on the chemosensors capable of detecting biologically relevant cations. The optical sensors are classified by the mechanisms of generation of an optical signal. Firstly, two main mechanisms of the generation of an optical response are considered that are characteristic of the chemosensors bearing only one signaling chromophore. Then, the examples of the use of energy transfer processes, the ability of chromophores to form exciplexes, as well as other photophysical processes for cation detection are discussed. In conclusion, the promising routes for further development of molecular devices for cation detection in biological media are highlighted.

2. Monochromophoric sensors based on the 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives

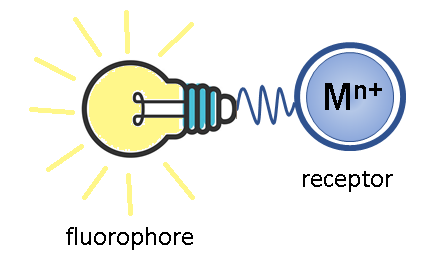

The molecular devices capable of altering the optical characteristics upon binding with a substrate are called optical chemosensors [12]. To act as a cation detector in solution, the simplest sensing molecule must include two functional units: a receptor, which represents an ionophore group that selectively binds with an analyte, and a fluorophore, which serves as a signaling element of the sensor and the changes in its luminescence parameters provide information about binding. Depending on the fact whether the receptor and fluorophore are conjugated into a single π-system or separated by a spacer, two main mechanisms for the generation of an optical response are distinguished [1, 12]: the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) and intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) mechanisms. Let us consider these processes in greater detail.

2.1. PET sensors

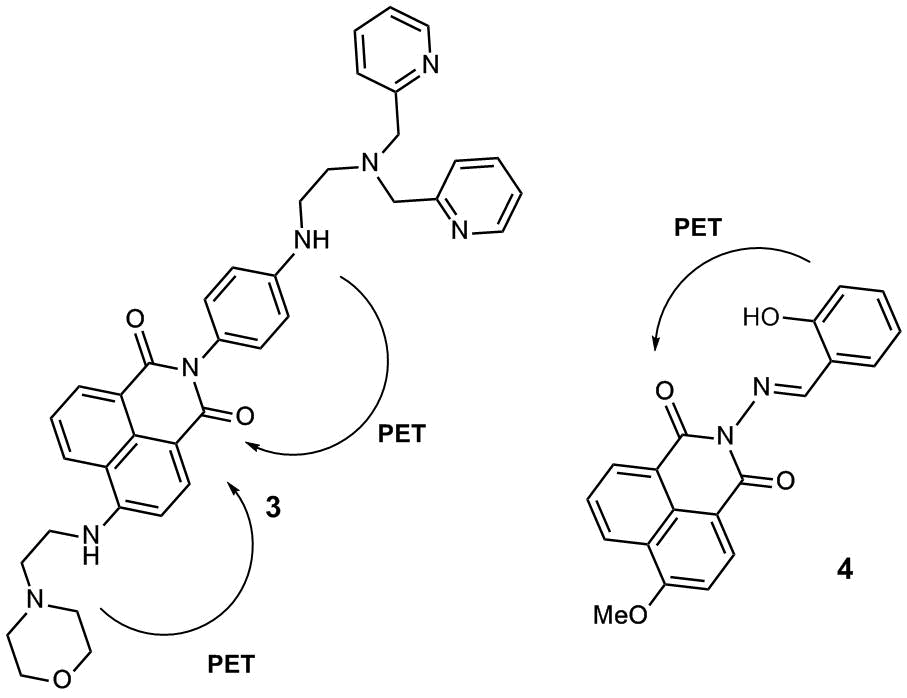

The components of a PET sensor are divided in the ground state by a spacer which can be, for example, a chain of several methylene units (Fig. 1). The photoexcitation of the fluorescent component leads to an electron transfer from the HOMO(–1) level localized on the fluorophore moiety to the LUMO level (see Fig. 1). In the case of cationic sensors, the receptor usually serves as an electron donor, which enables an electron transfer (PET) from the receptor HOMO to the singly occupied fluorophore HOMO in the excited state, resulting in the fluorescence quenching. The binding with a cation leads to a decrease of the receptor HOMO below the HOMO energy of the fluorophore, which makes the PET process impossible and leads to the enhancement of fluorescence of the signaling component. The 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives are extensively used as fluorescent components in the PET sensors since the naphthalimide core displays the electron-withdrawing properties in the S1-excited state [19].

Figure 1. Principal scheme of a PET sensor for cation recognition. The cation is presented as a sphere. The orbital origin (belonging to one or another sensor component) was established from the electron density distribution based on the results of quantum chemical calculations. The orbitals marked with a circle refer to the receptor moiety of the sensor, those unmarked refer to the chromophore moiety.

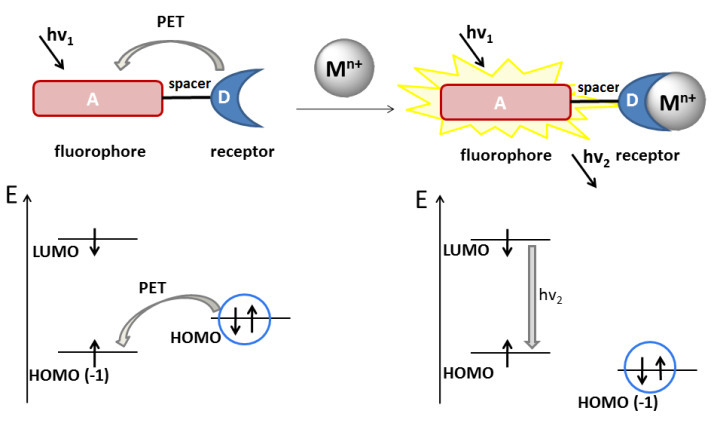

Scheme 1 presents the structures of crown ether derivatives of naphthalimides 1a–d and 2a–d that exhibit PET sensor properties towards metal cations in an acetonitrile solution [20–25]. Fluorescence of the naphthalimide moiety in free ligands 1a–d and 2a,c is effectively quenched by an electron transfer from the crown ether moiety of the molecule bearing electron-rich groups. The complexation by metal cations reduces the donor properties of the receptor moiety, which leads to a decrease in the efficiency of the PET process and fluorescence enhancement of the signal fragment. Compounds 1c and 2c bearing a methoxy group in the naphthalimide core and oxygen atoms in the crown ether moieties are responsive to magnesium and calcium cations [21]. The logarithms of the stability constants in acetonitrile are 6.57 for (2с)∙Mg2+ and 6.12 for (2с)∙Ca2+, whereas for 1с the corresponding values are equal to 5.61 and 5.34, respectively. The differences in the binding efficiency indicate that the presence of an aromatic core annulated with the macrocycle in the receptor structure increases the conformational rigidity of the latter and promotes a more favorable arrangement of the electron-donor oxygen and sulfur atoms for the cation coordination.

Scheme 1

The presence of the sulfur atoms in receptors 1a,b and 2a,b facilitates their binding with Ag+ and Hg2+ cations, whereas oxygen-containing receptors 1c,d and 2c,d serve as convenient complexing agents for alkaline earth metal cations (Ba2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+). A key difference of the sensors based on the sulfur-containing crown ethers from their oxygen-containing analogs is their capability of functioning in an aqueous medium owing to the formation of stable complexes. While detecting cations in aqueous media using the azacrown ether derivatives, it is important to optimize the medium pH since the protonation of the crown ether nitrogen atom and its binding with a metal cation will lead to the same analytical signal: fluorescence enhancement due to suppression of the PET process. Thus, studying the effect of the medium рН on the efficiency of fluorescence of 1а in water, we observed significant fluorescence enhancement of 1а at the pH values below 4.0, which was associated with the protonation of the crown ether nitrogen atom and blocking of the electron transfer process in the molecule [21]. At the рН values above 6.0, the fluorescence quantum yield of the ligand was low, which makes 1а a promising candidate for the application under physiological conditions. In a HEPES buffer* at рН = 7.3, 1а formed a complex with Ag+ ions of 1:1 composition; the binding with silver ions was accompanied by more than 75-fold fluorescence enhancement of 1а. The presence of Cu2+, Ca2+, Pb2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, or Cd2+ ions in solution did not afford any changes in the efficiency of emission of 1а, while Hg2+ and Fe2+ ions promoted only insignificant enhancement of fluorescence. A week response of 1а to mercury cations appeared to be surprising since azadithia-15-crown-5-ether is a well-known complexing agent for Hg2+. The analysis of the conditions in which this receptor can bind with Hg2+ cations showed that the efficient binding is observed in organic solvents (acetonitrile, chloroform, and THF), whereas the analogously high selectivity to Ag+ over Hg2+ ions was observed in a water–ethanol mixture (20 vol % of EtOH) at рН = 7.1 [22]. These data are in good agreement with the fact that, at the neutral pH, mercury(II) ions are fully hydrolyzed and exist as Hg(OH)2, whereas Ag+ ions are much less susceptible to hydrolysis. Recently, we have revealed [23] that the molecule of 1b bearing the same azadithia-15-crown-5 receptor moiety as in 1а displays a considerable fluorescence response to Hg2+ cations in a water–methanol mixture (40 vol % of MeOH) at pH = 4.7. A detection threshold of mercury ions for 1b was 25 nM. This value is close to the maximum admissible concentration of mercury ions in potable water prescribed at the level of 30 nM (World Health Organization) [26].

It should be noted that the efficient design of the PET sensors requires preliminary quantum chemical calculations of the frontier orbital energies. Thus, we have demonstrated [23] that the molecular orbital localized on the N-aryl moiety of 2b is lower than the frontier orbitals of the naphthalimide unit, which makes the PET process in this system inefficient (the fluorescence quantum yield of 2b in acetonitrile is 0.59 and the compound does not display an optical response to Hg2+ ions). At the same time, according to the results of calculations, the HOMO orbital in 1b localized on the N-aryl moiety is higher than the HOMO(–1) energy of the naphthalimide chromophore by 0.27 eV, which enables the realization of the PET process in this particular molecule. The optical spectroscopic studies revealed that, upon binding with mercury ions, 1b demonstrates a fluorescent response as a result of the suppression of the PET process and allows detecting this cation not only in acetonitrile but also in aqueous solutions [23].

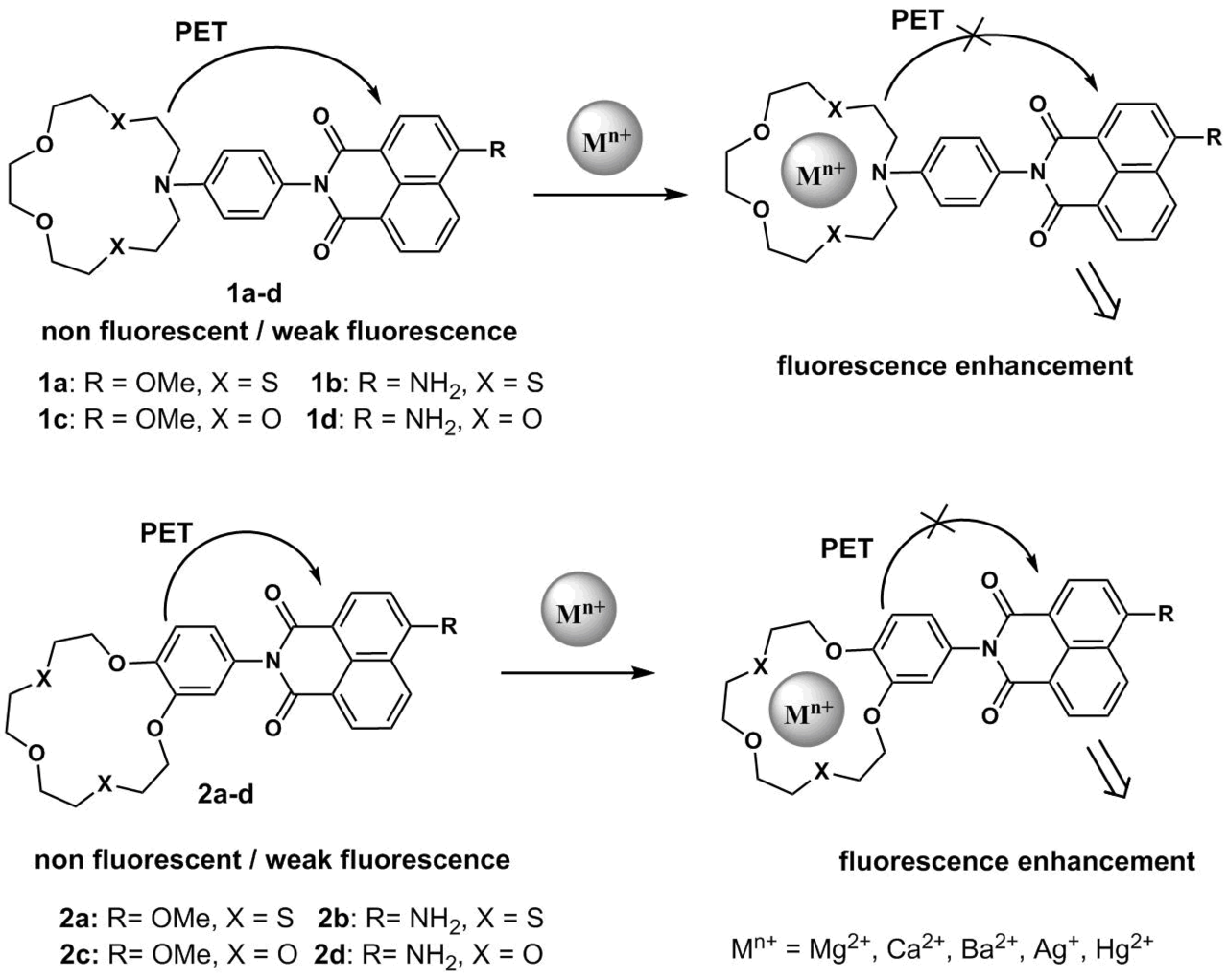

Sensor 3 bearing two PET donor moieties was suggested as a promising probe for zinc ions in lysosomes (Fig. 2) [27]. The receptor moiety of the molecule is represented by a dipicolyl ethylenediamine moiety attached to the naphthalimide fluorophore through a rigid phenylene unit. The presence of the amino group in the phenyl moiety leads to an increase in the HOMO energy of the sensor and strengthens the PET effect in the molecule, which provides the high sensitivity of 3 to the receptor coordination by the cation. The fourth position of the naphthalene core is occupied by a morpholine unit which plays a role of not only a vector group that provides the sensor accumulation in lysosomes but also the second donor moiety the electron transfer from which leads to the quenching of naphthalimide fluorescence.

Figure 2. Fluorescent PET sensors 3 and 4 for zinc cations.

In the pH range of 7.0–10.0, compound 3 demonstrates weak fluorescence in water with the quantum yield (φ) equal to 0.009, which indicates the emission quenching as a result of an electron transfer from the morpholine and aniline nitrogen atoms. The morpholine unit in 3 serves as a vector group for sensor accumulation in cell lysosomes, which are known to feature weakly acidic pH values. As the рН of an aqueous solution of 3 decreases from 7.0 to 5.0, the gradual enhancement of the ligand fluorescence is observed that is associated with the protonation of the morpholine unit (φ = 0.022 at рН = 5.0). The complex of 3 with zinc emits more intensively than the free ligand (φ = 0.049, рН = 7.0–10.0), which can be explained by the suppression of an electron transfer from the aniline nitrogen atom upon receptor binding with Zn2+ ions. The addition of zinc ions to a solution of 3 in a Tris-HCl buffer† at pH = 5.0 leads to the 5.5-fold enhancement of sensor fluorescence (therefore, at pH = 5.0, φ = 0.121 for complex (3)∙Zn2+ and 0.022 for free ligand 3). The fluorescent confocal microscopic studies showed that sensor 3 can penetrate MCF-7 cells, localize in lysosomes, and detect zinc cations in these cells.

PET sensor 4 for Zn2+ cations (Fig. 2) developed by our research group based on a derivative of 4-methoxy-1,8-naphthalimide bearing a salicylidene amino receptor group at the imide nitrogen atom demonstrated a fluorescence response for Zn2+ cations in an acetonitrile solution owing to the formation of ligand–metal complexes of 1:1 and 2:1 compositions [28]. Sensor 4 selectively binds with zinc cations compared to Mg2+, Ca2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Fe2+, and Pb2+; the quantum chemical calculations of the frontier orbitals showed that the response of 4 is connected with the suppression of the PET process in the free ligand.

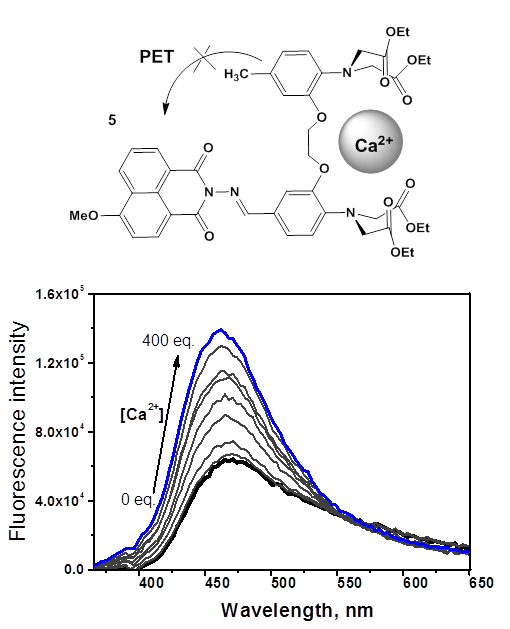

We also described fluorescent sensor 5 for calcium cations (Fig. 3) [29]. The receptor moiety in this compound was a derivative of one of the most popular Ca2+ chelating agents: 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA). BAPTA highly selectively binds with calcium ions in aqueous solutions and is low sensitive to the medium acidity in the physiological pH range. 4-Methoxy-substituted naphthalimide was chosen as a fluorophore unit since it possesses a relatively high electron-deficient character in the excited state, which, compared to the 4-amino derivatives often used in the design of sensors, makes fluorescence switching by the PET mechanism more contrast.

Figure 3. Structure of the PET fluorescent sensor for calcium cations (5). Changes in the fluorescence spectrum of 5 (4∙10–6 M) in the presence of Ca(ClO4)2 in water (the excitation wavelength was 350 nm) [29]. (Reprinted from M. A. Zakharko et al., Mendeleev Commun., 2020, 30, 332–335. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2020.05.024. Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier)

Using optical and NMR spectroscopy, it was shown that compound 5 forms with Ca2+ only one type of complexes of 1:1 composition. Figure 3 depicts the results of the spectrofluorometric titration of 5 with calcium perchlorate in water. The observed enhancement of ligand fluorescence upon binding with Ca2+ is connected with the suppression of an electron transfer from the HOMO orbital localized on the receptor moiety of 5 to the singly occupied HOMO(–1) level of the naphthalimide unit. The logarithm of the binding constant of 5 with Ca2+ in water was 5.4 ± 0.1, and the detection threshold was 4·10–7 M. The latter parameter gives compound 5 an advantage over most of the sensor systems for optical detection of calcium in water reported for the last decade [30].

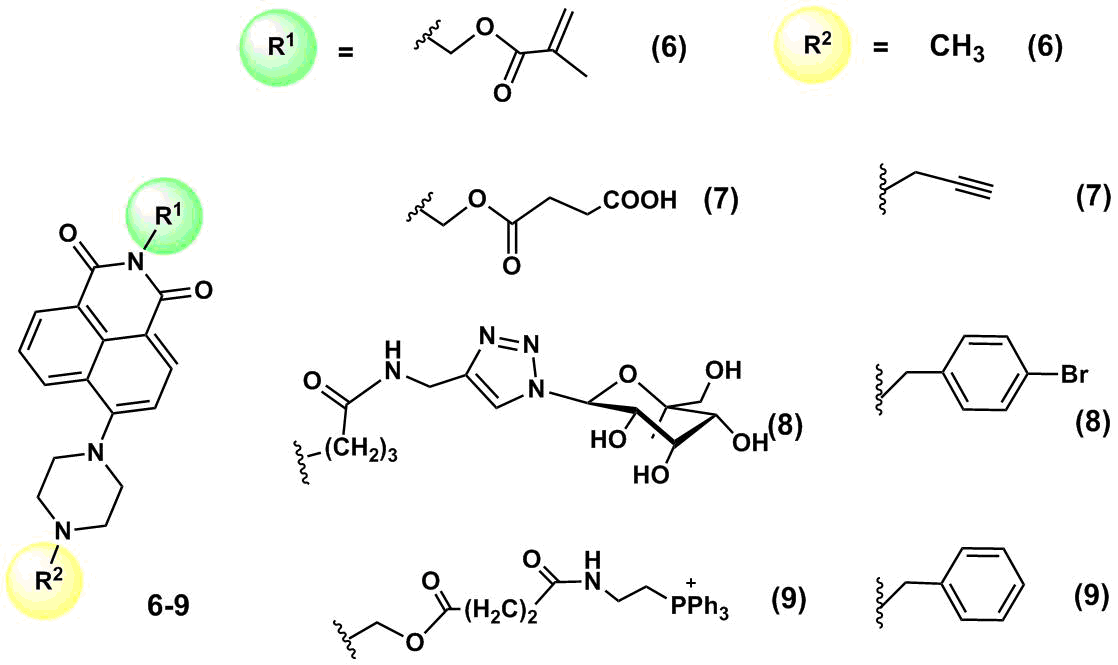

A series of fluorescent pH-sensors 6–9 were developed based on 4-piperazine-substituted naphthalimides (Fig. 4) [31–34]. These pH sensors feature the same receptor (a piperazine moiety at the fourth position of the naphthalimide core) but contain different functional moieties at the imide nitrogen atom. Compound 6 involves a methacrylate moiety that offers an opportunity for sensor polymerization and the creation of thin films for in vitro pH analysis. Sensor 7 contains a succinic acid residue for further immobilization on nanoparticles. Compound 8 includes a galactose moiety that simplifies its penetration into cells via endocytosis and accumulation in lysosomes. Finally, sensor 9 contains a positively charged triphenylphosphonium group that promotes its delivery to mitochondria. The emission of compounds 6–9 in the alkaline medium is quenched as a result of an electron transfer from the electron-rich piperazine moiety. The protonation of the piperazine nitrogen atom blocks the PET process, which leads to fluorescence enhancement. The values of рКа for these sensors are 6.83, 6.47, 6.73, and 6.18, respectively; the working values of the medium pH are within 4.5–7.5.

Figure 4. Structures of рН sensors 6–9.

Sensor 6 was used to obtain thin polymeric films for measuring the value of pH in the extracellular medium [31]. It was polymerized on an ion-permeable polymer matrix poly(acrylamide-co-hydroxyethyl methacrylate; the resulting film displayed the pH sensor properties for monitoring the changes in the medium acidity during the metabolism of Escherichia coli. One of the metabolic products of this bacterium is carbon dioxide that leads to an increase in the medium pH. To measure the value of the nutritive medium pH in which E. Coli was cultured, the medium was placed in a quartz cuvette; then, a small amount of mineral oil was added to prevent evaporation of CO2. A thin film bearing fluorophore 6 was placed in a cuvette at an angle of 45° and the film fluorescence was registered on a spectrofluorometer at 517 nm. The measurement of the fluorescence intensity at 517 nm allowed for defining the number of bacteria in the cuvette at the specified time. Hence, the immobilization of ion-sensitive fluorophores in thin films allows one to obtain the materials for optical devices that can multiply be used for monitoring the environment or different biological processes in real time.

He et al. [32] obtained carbon nanodots which surface was modified with fluorophore 7 and morpholine molecules that served as vector groups for the delivery of nanodots to lysosomes. Upon photoexcitation at the wavelength of 380 nm, the hybrid system demonstrated two emission peaks: at 455 nm, which corresponds to the emission of the carbon nanodots themselves, and 527 nm, which is responsible for the emission of the naphthalimide fluorophore. An increase in the medium pH promoted the quenching of fluorescence of the naphthalimide component, whereas the emission band of the nanodots remained unchanged, which allowed for ratiometric measurement of the medium pH inside cells. The modification of nanodots with fluorophores is an attractive strategy for the development of ionophore systems since, owing to the small particle sizes and ample opportunities for the modification of their surface, the nanodots can afford biocompatible photostable hybrid materials that would possess cell permeability. Thus, the authors of this work demonstrated the ability of carbon nanodots modified with 7 to penetrate a cell membrane and accumulate in lysosomes, as well as to display a fluorescence response to the variation of the lysosome pH in HeLa cells.

2.2. ICT sensors

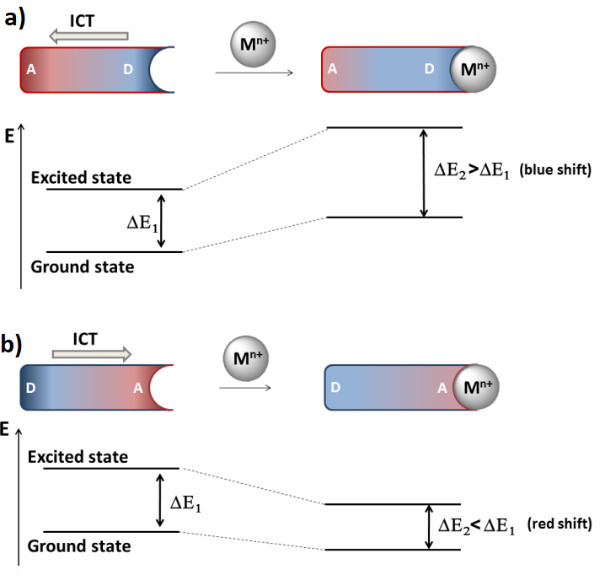

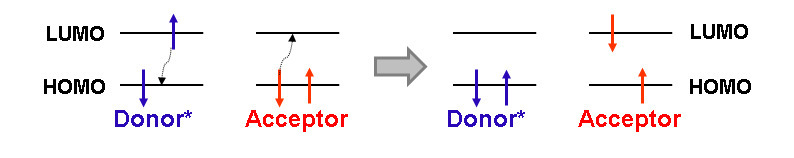

To realize the ICT process, one or several receptor atoms must be included in a conjugated π-system of a fluorophore (Fig. 5). This type of sensors is often represented by the chromophores bearing electron-donor (ED) and electron-withdrawing (EW) groups at different ends of the π-system; the photoexcitation results in the molecule polarization: a transfer of electron density between the donor and acceptor parts of the molecule. The greater the energy required for a charge transfer upon photoexcitation, the greater a red shift of the chromophore absorption.

The complex resulting from the ligand binding with a cation features another distribution of electron density in the molecule. Figure 5 depicts the spectral changes that will be observed upon coordination of the ICT sensor with a cation in the cases when the receptor is located in the ED or EW parts of the molecule. Upon coordination of the cation with the receptor in the composition of the ED sensor moiety (Fig. 5а), the electron density on the receptor reduces, the complex becomes less polar compared to the initial ligand, and its transition to the excited state requires higher energy, which is expressed in a hypsochromic shift of the molecule absorption band upon binding with the cation. The fluorescence spectrum upon complexation will consequently display a bathochromic shift. A reverse situation (an increase in the energy gap and a blue shift of the absorption and emission spectra) is observed in the case when the receptor moiety of the sensor is an acceptor in the ICT chromophore (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5. Energy diagram that explains the spectral shifts upon binding of cations with the ICT sensor: (a) ED substituent in the fluorophore structure is included in the receptor; (b) EW substituent in the fluorophore structure is included in the receptor.

In general, an analytical signal of the PET sensors is fluorescence enhancement or quenching. The enhancement is the most preferable signal since it is characterized by the greater values of an optical response and signal/noise ratio. The analytical signal of the ICT sensors is a shift of the absorption and emission maxima upon binding with cations, which opens the way to the so-called naked-eye detection (a human eye is more sensitive to a change in the wavelength of the emitted light than to a change in the fluorescence intensity [35]). In many sensor systems, both of the mechanisms for the generation of an optical signal are realized simultaneously.

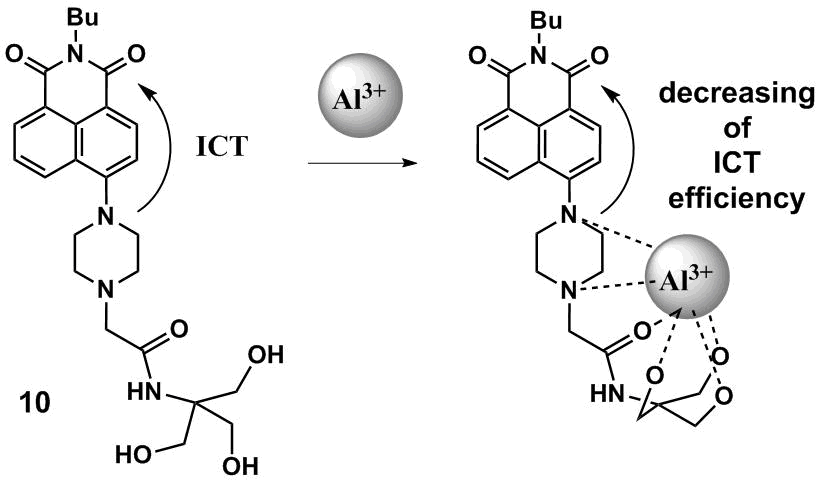

The development of the fluorescent ICT sensors based on the 1,8-naphthalimide optical platform often implies the involvement of electron-donor substituents at the fourth position of the naphthalene core in the receptor moiety. Thus, 4-piperazine-substituted derivative of naphthalimide 10 (Scheme 2) was suggested [36] for probing aluminum cations in methanol. The coordination of the nitrogen atom, which lone pair is included in the conjugated system of the naphthalimide residue, by Al3+ ions leads to weakening of its donor properties and reduction in the amount of energy that is required for a charge transfer in the system during photoexcitation, which results in a short-wave shift of the absorption and fluorescence maxima of the ligand upon coordination with metal ions.

Scheme 2

The enhancement of fluorescence of 10 upon binding with Al3+ ions is connected with the blocking of non-emissive relaxation routes of the molecule excited state as a result of the formation of a structurally rigid complex with aluminum cations (the so-called chelation enhanced fluorescence is the fluorescence enhancement as a result of chelation [37]). In methanol, the logarithm of the binding constant is 4.88. Compound 10 reversibly binds with aluminum cations with high selectivity compared to other metal cations in aqueous solutions, which opens the way to its further application in ecological analysis.

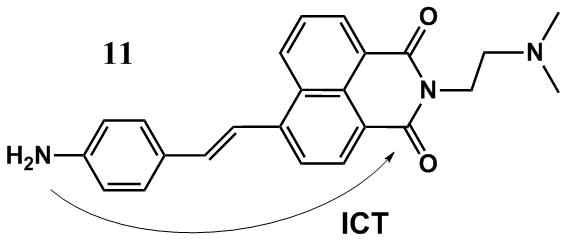

Fluorescent pH sensor 11 (Fig. 6) contains two electron-rich amino groups which protonation causes different spectral changes [38]. Compound 11 is ICT type chromophore since it contains an aminostyryl substituent with the marked electron-donor properties that are in conjugation with the carbonyl groups of the naphthalimide unit. A short-wave band in the absorption spectrum of 11 at ca. 310 nm (toluene) corresponds to the local π–π* transitions; a long-wave peak is located in the range of 435–470 nm and refers to a charge energy band. As the pH value of a DMSO–water (3:1, v/v) mixture reduces from 6.0 to 3.0, the more basic dimethylamino group that plays the role of the PET donor in the system is subjected to the protonation first (а = 4.81). This process leads to the enhancement of sensor fluorescence. The binding with the ICT donor proton, NH2 group, leads to a drastic reduction in its electron-donor properties, which affords an increase in the energy gap between the frontier molecular orbitals of the complex and the initial ligand. This results in a hypsochromic shift of the absorption and emission maxima of the sensor upon complexation.

Figure 6. Structure of рН sensor 11.

3. Bis(chromophoric) sensors based on the 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives

The introduction of the second chromophore moiety into structures of sensor molecules allows one to obtain ion-sensitive molecular systems in which the photophysical processes such as energy transfer and formation of excimers/exciplexes are realized [39]. Particular attention to these processes is stipulated by the possibility of a shift of the ionophore absorption maxima to a longer-wave region as well as the possibility of the creation of ratiometric sensor devices on their base. The ratiometric method is based on the measurement of the fluorescence intensities at different wavelengths, which ratio changes depending on an analyte concentration [39–41]. Such an approach is of special interest for the application in biological systems, in particular, for in vitro and in vivo analyses since it does not require the definition of a precise sensor concentration in the object under consideration and provides internal calibration of an analytical signal by the medium parameters (temperature, viscosity, polarity, etc.). In the following sections, we will consider the examples of the bis(chromophoric) molecular systems in which the processes of energy transfer and excimer formation are realized.

3.1. Sensors based on the Förster resonance energy transfer mechanism

A non-emissive transfer of the photoexcitation energy by the Förster mechanism is nowadays one of the most popular photophysical processes that are used in the development of optical sensors [2, 12, 16]. The Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) results from the dipole–dipole interaction between two photoactive moieties (Fig. 7). The efficiency and rate of an energy transfer by the Förster mechanism between chromophores (donor (D) and acceptor (A)) depend on several parameters: a distance between the photoactive moieties, a relative orientation of the dipole moments of electron transfers of two chromophores, as well as the overlapping of the fluorescence spectra of D and A [42, 43]. The shorter the distance between the chromophores and the greater the overlap integral of the absorption spectrum of A and the fluorescence spectrum of D, the more efficient the energy transfer in the D–A system. The application of the FRET processes for the development of sensor devices is based on the changes in the energy transfer efficiency as a result of an increase/decrease in the overlapping degree of the absorption and emission spectra of D and A, the distance between them, as well as owing to acceleration or inhibition of the competitive processes.

Figure 7. Principle of the FRET process.

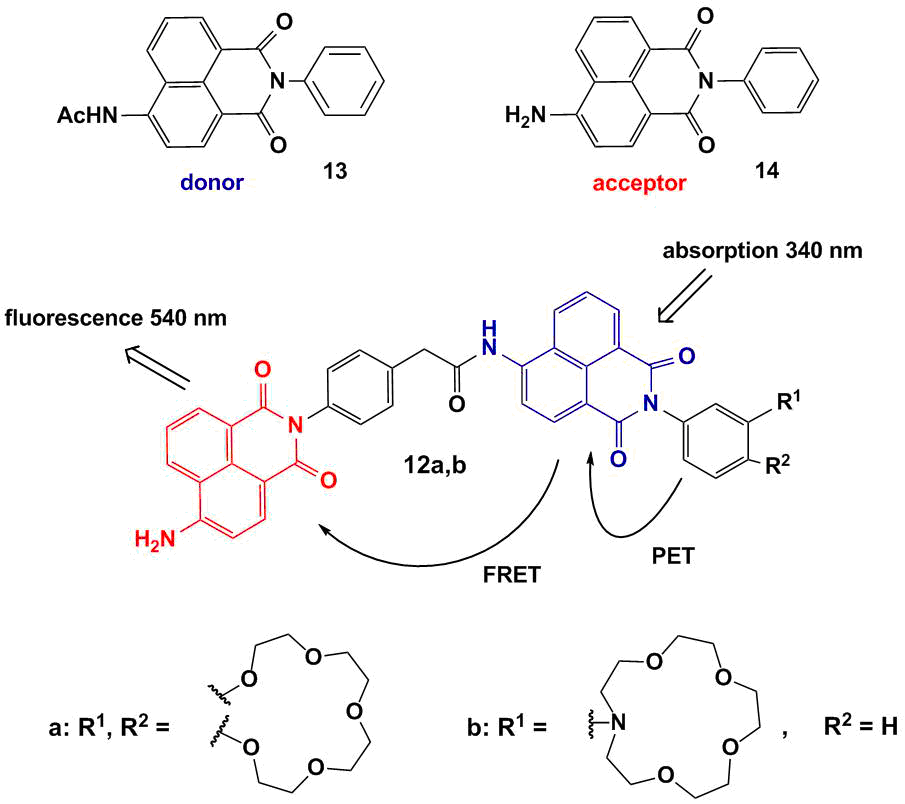

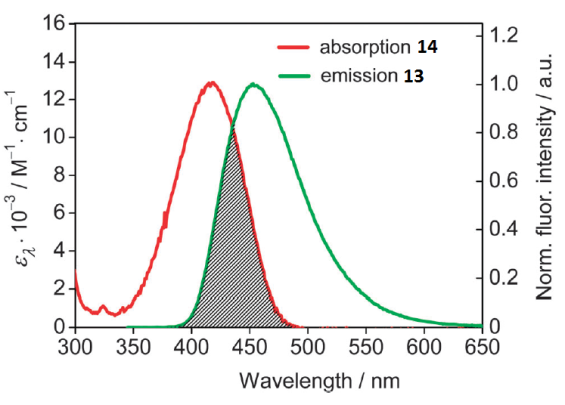

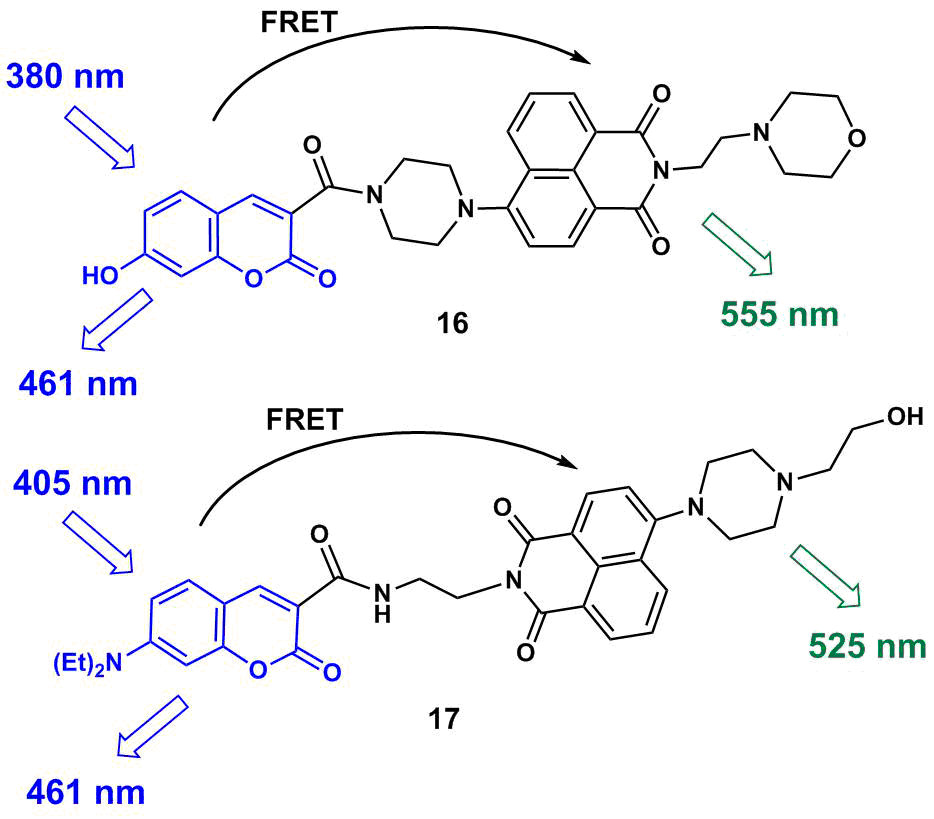

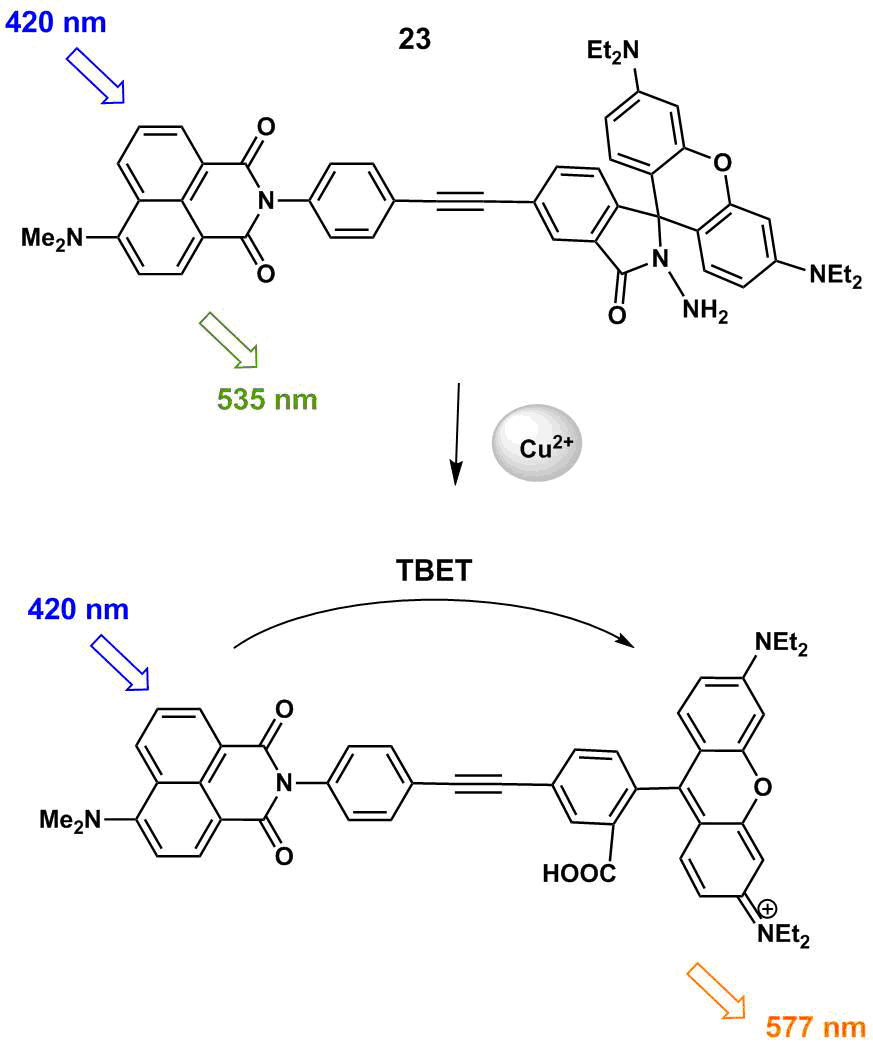

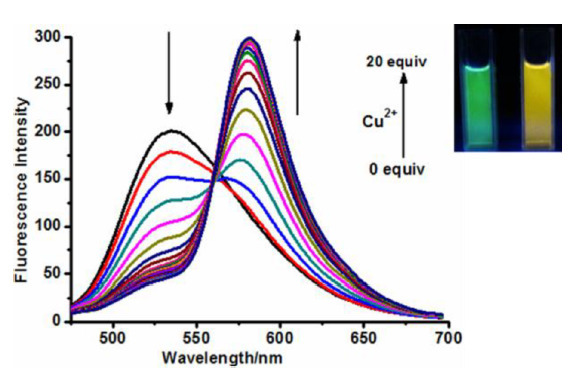

Bis(chromophoric) fluorescent sensors 12a,b based on the 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives bearing benzo-15-crown-5 and N-phenyl-aza-15-crown-5 ether moieties as receptors were described (Fig. 8) [44]. To fulfill the main condition for the realization of the FRET process in the systems, naphthalimide derivatives 13 and 14 were chosen as the energy donor and acceptor, respectively (Fig. 8). As can be seen from Fig. 9, the emission band of 14 located in the range of 440–460 nm partially overlaps with the absorption spectrum of 13 that has the maximum at 417 nm.

Figure 8. Structures of sensors 12a,b and monochromophores 13 and 14.

Figure 9. Overlap between the absorption spectrum of 14 and the emission spectrum of 13 in acetonitrile. The concentrations of both compounds were 5.0∙10–6 M. The excitation wavelength was 340 nm. [P. A. Panchenko et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2015, 17, 22749–22757. DOI: 10.1039/c5cp03510d] – Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies

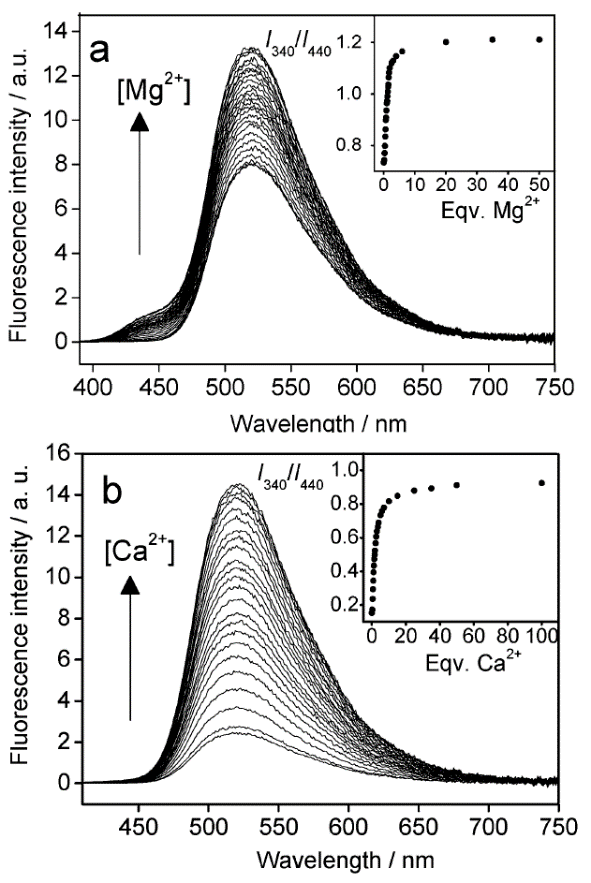

As it was mentioned in the first section, the introduction of a crown ether unit into the naphthalimide-based fluorophore can lead to the realization of the PET process in the system, which results in the quenching of naphthalimide fluorescence. Hence, the emission of the donor component of bis(chromophores) 12a and 12b is quenched as a result of the realization of two competitive processes in the systems: an electron transfer and energy transfer (Fig. 8). The PET process in compounds 12a,b is cation-dependent: in the presence of metal cations capable of coordinating the crown ether moiety, its efficiency reduces. The blocking of the PET process leads to the growth of fluorescence intensity of the acceptor component as a result of an energy transfer from the donor. The functioning mechanism of sensors 12a and 12b was confirmed by the stationary and time-resolved optical spectroscopy. Figure 10 presents the results of spectrofluorometric titration of acetonitrile solutions of 12a and 12b with magnesium and calcium perchlorates, respectively. The addition of the metal cations to the sensor solutions causes the growth of fluorescence intensity at ca. 520 nm, which corresponds to the emission maximum of 4-aminonaphthalimide.

Figure 10. Changes in the fluorescence spectra of compounds 12a (a) and 12b (b) in acetonitrile (the excitation wavelength was 340 nm). The insets show the ratio of the fluorescence intensity at 520 nm measured using the excitation light of 340 nm (I340) to that at 520 nm measured using the excitation light of 440 nm (I440). (a) The concentration CL = 4.5∙10–6 M for ligand 12a; (b) the concentration CL = 6.5∙10–6 M for ligand 12b. [P. A. Panchenko et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2015, 17, 22749–22757. DOI: 10.1039/c5cp03510d] – Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies

An important peculiarity of 12a and 12b is the possibility of ratiometric measurements of analyte concentrations. The fluorescent signal that arises during photoexcitation of the donor component of the bis(chromophore) at the wavelength of 320 nm can be calibrated relative to a fluorescent response of the acceptor component excited with the wavelength of 440 nm since the fluorescence intensity of the acceptor is not sensitive to the presence of magnesium or calcium cations.

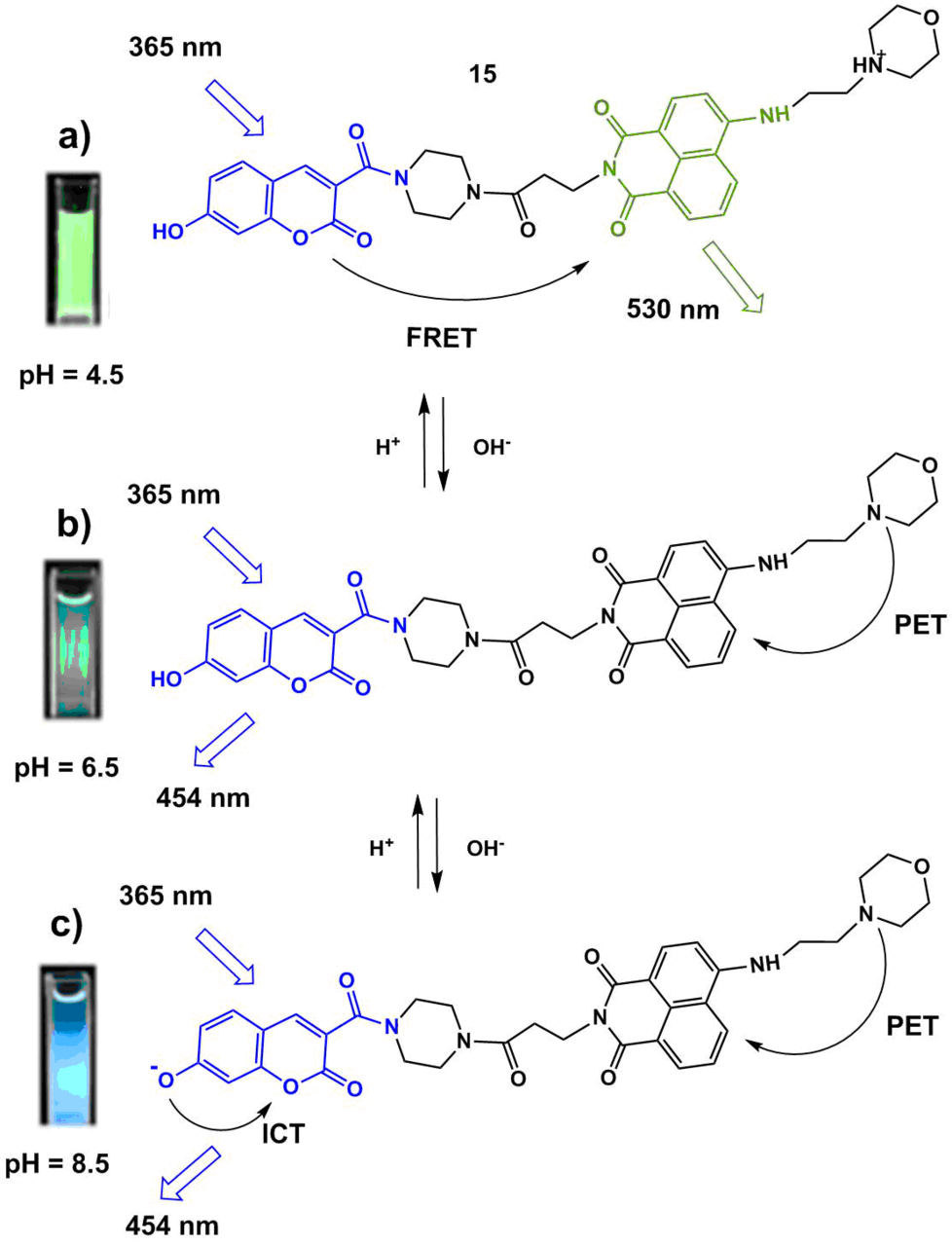

The functioning mechanism of fluorescent sensor 15 (Scheme 3) developed for the definition of the lysosome pH is based on a combination of the ICT, PET, and FRET processes [45]. Dong et al. suggested an interesting strategy for the development of a ratiometric sensor, which consists in the application of the FRET pair of fluorophores each of which contains a functional moiety that allows one to control the processes of charge or electron transfer depending on the medium acidity. The optical coumarin and naphthalimide platforms were chosen as the donor and acceptor components of the FRET pair. Such a combination of the chromophores is often used for the creation of ionophore systems since the fluorescence spectra of the coumarin derivatives often significantly overlap with the absorption spectra of 4-amino-substituted naphthalimide and, moreover, both of the compounds are efficient luminophores and possess high photostability.

Scheme 3

The absorption spectrum of 15 in a neutral medium (рН = 7.4) represents a superposition of the absorption spectra of the coumarin (λmax = 400 nm) and naphthalimide (λmax = 430 nm) chromophores, which indicates the absence of their interaction in the ground state. In the acidic medium (at рН = 4.5), the morpholine unit of the molecule is protonated, and the energy transfer process is realized in the system: upon photoexcitation of the coumarin chromophore (λex = 380 nm), one can observe the appearance of intensive green luminescence of 4-aminonaphthalimide (λmax = 530 nm, Fig. 11а, Scheme 3а). In system 15, the energy transfer is realized not with 100% efficiency, at pH = 4.5, besides the intensive band at 530 nm, there is observed weak fluorescence at 454 nm that corresponds to the coumarin emission (Fig. 11b, Scheme 3b). An increase in the medium рН to 6.5 causes a reduction in the intensity of the band with the maximum at 530 nm and the appearance of weak light blue emission with the maximum at 454 nm (Fig. 11b, Scheme 3с). These spectral changes evidence the disappearance of the protonated morpholine form and blocking of the emissive relaxation of the naphthalimide unit as a result of an electron transfer. A further increase in the medium pH to 8.5 causes a bathochromic shift of the sensor absorption bands, which testifies the deprotonation of the coumarin hydroxy group. The appearance of the negative charge on the oxygen atom significantly enhances its electron-donor properties, which results in an increase in the efficiency of the ICT process in the system and leads to the growth in the coumarin fluorescence intensity. Hence, an increase in the pH values from the acidic (4.5) to alkaline (8.5) reaction of the medium is accompanied by a change in the intensities of the fluorescence bands with the maxima at 454 nm and 530 nm, which is connected with a change in the efficiencies of the charge and electron transfer processes in the system. The dependence of the ratio of luminescence intensities I530/I454 appeared to be linear in the pH range of 4.0–6.5, and that of I454/I530—in the pH range of 6.0–8.0. The potential of sensor 15 for practical application was demonstrated by monitoring the chemically induced changes in the pH values in HeLa cells.

Figure 11. Absorption (а) and fluorescence (b) spectra of the solutions of рН sensor 15 in a Britton–Robinson buffer (5% MeOH) at different pH values. The concentration of the compound was 23.5 μM; the excitation wavelength was 380 nm [45]. (Reprinted with permission from B. Dong et al., Anal. Chem., 2016, 88, 4085–4091. DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00422. Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society)

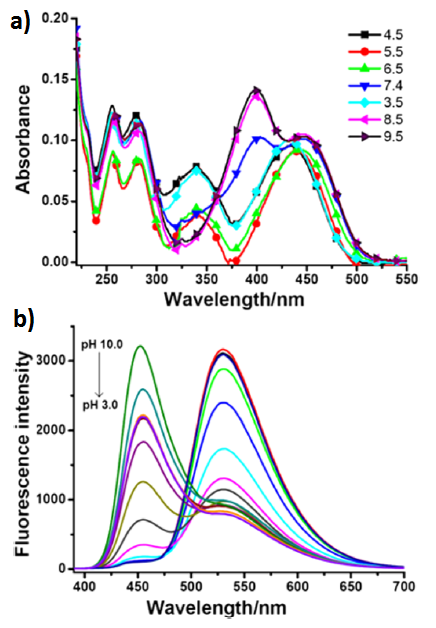

The fluorescent ratiometric pH probes based on the FRET pair of naphthalimide and coumarin 16 and 17 (Fig. 12) were reported [46, 47]. The excitation of the coumarin chromophore in the composition of 16 at рН = 2.0 leads to the appearance of two fluorescence bands with the maxima at 461 and 555 nm that are responsible for the emission of the coumarin and naphthalimide units, respectively. This fact indicates that the photoexcitation energy in 16 is partially transferred from the coumarin to the naphthalimide moiety. The morpholine unit is protonated and the PET process is not realized in the molecule. As the solution pH increases to 6.0, there is observed simultaneous growth of the intensities of both fluorescence bands, although according to the FRET theory, the emission of the donor moiety must be quenched. The authors assume that, in this pH range, the main contribution to the emission efficiency of the coumarin being in the deprotonated form is made by a charge transfer inside the chromophore rather than an energy transfer to the naphthalimide unit. A further increase in the solution pH from 6.0 to 11.0 causes the enhancement of the coumarin emission, while the naphthalimide fluorescence, in contrast, is quenched as a result of an electron transfer from the deprotonated morpholine unit of 16. Hence, growth of the medium pH causes changes in the intensities of both fluorescence bands of 16; the intensity ratio I461/I555 can be used for the ratiometric measurement of the medium acidity in the pH range from 4.5 to 11.0.

Figure 12. Structures of рН sensors 16 and 17.

A functioning principle of 17 is based on the variation of the efficiency of an energy transfer as a result of the blocking of the PET process with increasing medium acidity. At pН = 10.0, the fluorescence spectrum of 17 shows only the emission band of the coumarin unit with a maximum at 461 nm due to the realization of an electron transfer from the morpholine ring to the naphthalimide moiety, which makes the FRET process impossible in the system. In the acidic conditions (рН = 3.0), in contrast, the naphthalimide chromophore emits mainly at 525 nm due to protonation of the morpholine unit and realization of a photoexcitation energy transfer in the system. The efficiency of the FRET process in 17 is below 100%; therefore, in a highly acidic medium, there is observed a residual low-intensity emission peak of the coumarin which allows one to perform the ratiometric definition of the medium pH using the intensity ratio I467/I525. The working values of the medium pH for ratiometric probe 17 ranges from 4.0 to 10.0. Therefore, the working pH intervals of 16 and 17 involve the conventional values of the lysosome pH (4.5–5.0) as well as the normal physiological values of the cytoplasm pH (6.4–7.4). The tests of 16 and 17 on HeLa cells showed that 16 is selectively accumulated in lysosomes owing to the presence of the morpholine unit; compounds 16 and 17 do not exert toxic effects in the concentrations explored (10 and 5 μM, respectively) and thus enable in vitro pH analysis.

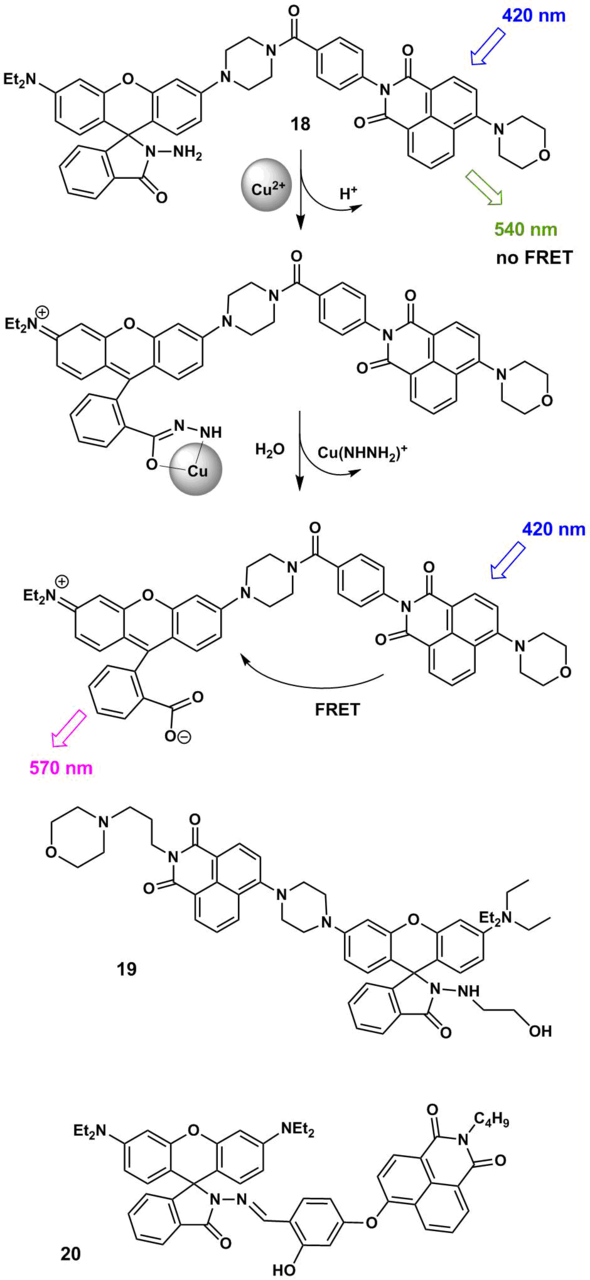

The application of rhodamine dyes as acceptor components of the FRET pairs offers ample opportunities for the design of pH sensors and cation probes [48–50]. The cation-induced opening of a spyrolactam ring of rhodamines gives rise to the colored form that participates in an energy transfer. Fluorescent sensors for copper cations 18 and 19 bearing a spyrolactam ring were reported (Scheme 4) [51, 52]. It should be noted that the development of efficient probes for copper ions is not a simple task since the emission of many fluorophores is quenched due to the interaction with paramagnetic copper ions [53].

Scheme 4

The excitation of the naphthalimide chromophore in compounds 18 and 19 in a mixture of polar solvents (water and acetonitrile) gives rise to a fluorescence peak with a maximum at 540 nm since the rhodamine dye is mainly in the uncolored spyro form and an energy transfer, in this case is, impossible. The binding of 18 and 19 with copper cations is accompanied by the hydrolysis of the hydrazide rhodamine derivative and the formation of the open form of rhodamine B that absorbs in the range of 500–560 nm. This region is overlapped by the broad emission band of the naphthalimide component (450–650 nm). Therefore, in the complex with the cation, the condition for the occurrence of the FRET process is fulfilled, which leads to the appearance of an analytical signal: a fluorescence band with a maximum at 570 nm that corresponds to the emission of the rhodamine component of the pair. Compounds 18 and 19 are highly sensitive and selective probes for the ratiometric detection of copper cations in lysosomes. It should be noted that 18 and 19 allow for detecting copper ions in water with the detection thresholds of 18 nM and 1.45 nM, respectively. For the fluorescent sensors, these values are excellent characteristics: for example, the detection threshold for copper ions of the modern technique of capillary electrophoresis with UV detection (CE-UV method) used in biological analysis composes about 30 nM [54].

Naphthalimide and rhodamine conjugate 20 (Scheme 4) also allows for the colorimetric and spectrofluorometric detection of Cu2+ ions in solution and in vitro with the detection threshold of 0.018 μM [55].

FRET pairs of the naphthalimide and rhodamine B 21 and 22 (Scheme 5) were obtained that contain thiourea moieties capable of providing the affinity to mercury ions [56, 57]. A functioning principle of ratiometric probes 21 and 22 is based on the cation-induced opening of a spyrolactam ring of the rhodamine unit, which is accompanied by an increase in the efficiency of an energy transfer in the system. The binding of 22 with Hg2+ ions is irreversible since it is accompanied by the desulfurization and cyclization of the thiourea moiety directly bound to the rhodamine chromophore.‡ Ligand 21 has two coordination sites for mercury ions: one of the thiourea moieties in the composition of 21 undergoes desulfurization in the presence of Hg2+, the complexation of the second one with Hg2+ is reversible. Complex 21 with Hg2+ releases the cation under the action of potassium iodide and demonstrates the reverse fluorescence switching upon precipitation of mercury iodide. The measurement of the ratio of luminescence intensities of 21 at 593 and 535 nm enables the ratiometric detection of the content of mercury ions in a methanol–water solution (1:2, v/v).

Scheme 5

3.2. Through-bond energy transfer sensors

An energy transfer proceeds by the Förster mechanism in the absence of π-conjugation between the components of a bis(chromophoric) system in the ground state and requires the overlapping of the donor fluorescence and acceptor emission spectra. There is also another mechanism of an electron excitation energy transfer—through-bond energy transfer (TBET)—that is realized in a system of two photoactive moieties connected with each other through a π-conjugated spacer in which one of the chromophores is removed from the conjugation to some extent owing to the twisted conformation of the molecule [58, 59]. The TBET process possesses certain features that make it an attractive tool for the creation of biosensors [60]. In particular, this mechanism is not limited by the condition of the overlapping of the donor emission and acceptor absorption spectra, which not only significantly extends the spectrum of potential chromophoric components for the TBET systems but also allows one to obtain the systems with much higher pseudo-Stokes shifts§ than it would be possible within the FRET mechanism. This fact is extremely important since a difference in the wavelengths of the excited and emitted light directly affects the contrast ratio of the resulting images upon detection by fluorescence microscopy. As a rule, through-bond energy transfer rate constants exceed those provided by the Förster mechanism, and the TBET process, under other conditions being equal, proceeds with the higher efficiency [54, 56].

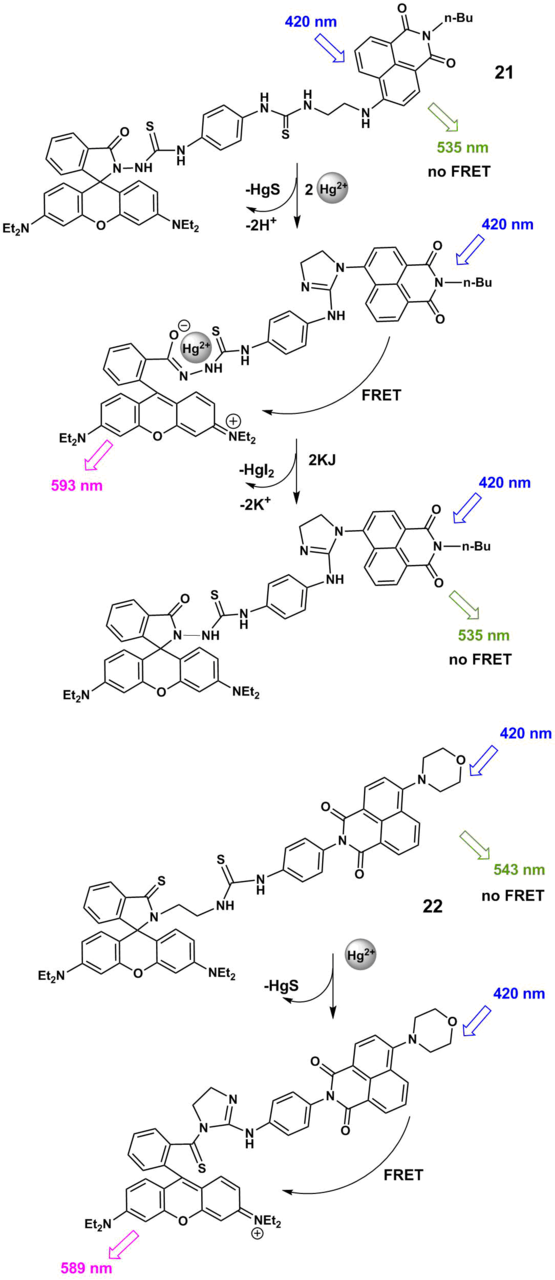

TBET fluorescent sensor 23 (Scheme 6) based on 4-dimethylaminonaphthalimide and rhodamine B was reported that allows for copper cation detection in aqueous solutions [61].

Scheme 6

In the absence of Cu2+ ions, the rhodamine unit exists in the closed spyro form, which makes an energy transfer in the system impossible and the photoexcitation of the naphthalimide moiety affords a fluorescence band in the spectrum with a maximum at 535 nm corresponding to this unit (Fig. 13).

Figure 13. Fluorescence ratio of 23 (5 μM) in response to the presence of Cu2+ ions (0–20 eq.) in MeCN–H2O (20:1, v/v) buffered with Tris-HCl (pH = 7.4, 10 mM), λex = 420 nm. An inset shows fluorescence before and after the addition of Cu2+ ions [61]. (Reprinted with permission from J. Fan et al., Org. Lett., 2013, 15, 492–495. DOI: 10.1021/ol3032889. Copyright (2013) American Chemical Society)

The addition of copper cations to a solution of 23 leads to the appearance of the open rhodamine form that plays the role of the TBET acceptor in the system. This process is accompanied by a drop in the intensity of the band at 535 nm and the appearance of the rhodamine fluorescence band in the range of 577 nm. The energy transfer efficiency in the system composes 81.3%; the authors suggest the TBET nature of this process based on the fact that a torsional angle between the naphthalimide and rhodamine moieties in 23 with the open rhodamine form optimized by the quantum chemical calculations composes 5°; however, they do not exclude the possibility of simultaneous realization of the TBET and FRET processes. The efficiency of sensor functioning in vitro was studied on MCF7 cells. It was shown that 23 penetrates a cell membrane and does not exhibit significant cytotoxicity, enabling the detection of copper ions with the threshold of 3.77∙10–7 M.

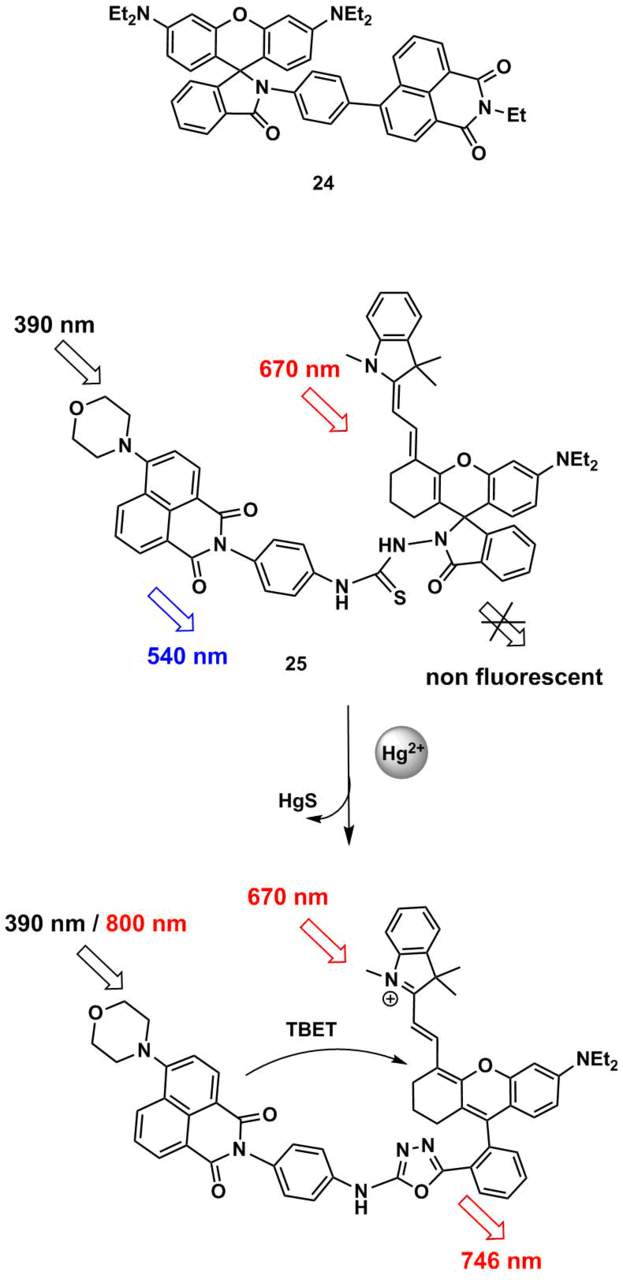

ТВЕТ chemosensors 24 and 25 (Scheme 7) were suggested for the detection of mercury ions in aqueous solutions [62, 63]. A fluorescent response of 24 and 25 is caused by the cation-induced opening of a spyrolactam ring, which, in the case of 25, is accompanied by desulfurization, making the cation binding irreversible. Owing to the introduction of the conjugated indoline moiety, the chromophoric system of the rhodamine component of compound 24 demonstrates the long-wave fluorescence (λmax = 746 nm, EtOH–H2O (1:1, v/v)). Furthermore, 4-morpholinylnaphtahlene displays two-photon absorption properties, which allows one to excite the sensor molecule in the range of 800 nm. The possibility of photoexcitation of 24 in the infrared region makes this probe a promising candidate for investigations on cells.

Scheme 7

3.3. Sensors functioning through formation/decomposition of excimers

The ability of chromophores to form excimers upon photoexcitation is also utilized in the development of sensors for ratiometric measurements. As is known, an excimer represents a photoexcited dimeric complex in which the excitation energy is distributed between two components [64]. The interaction of π-systems of the dimer components gives rise to a fluorescence peak in the spectrum which is bathochromically shifted relative to that of the monomer [64]. The ratiometric approach is realized owing to the measurement of the relative intensities of the monomer and excimer bands in the sensor fluorescence spectrum upon its complexation with an analyte. Nowadays, there are only several reports devoted to the sensors based on 1,8-naphthalimide which functioning principle is based on the formation/decomposition of excimers.

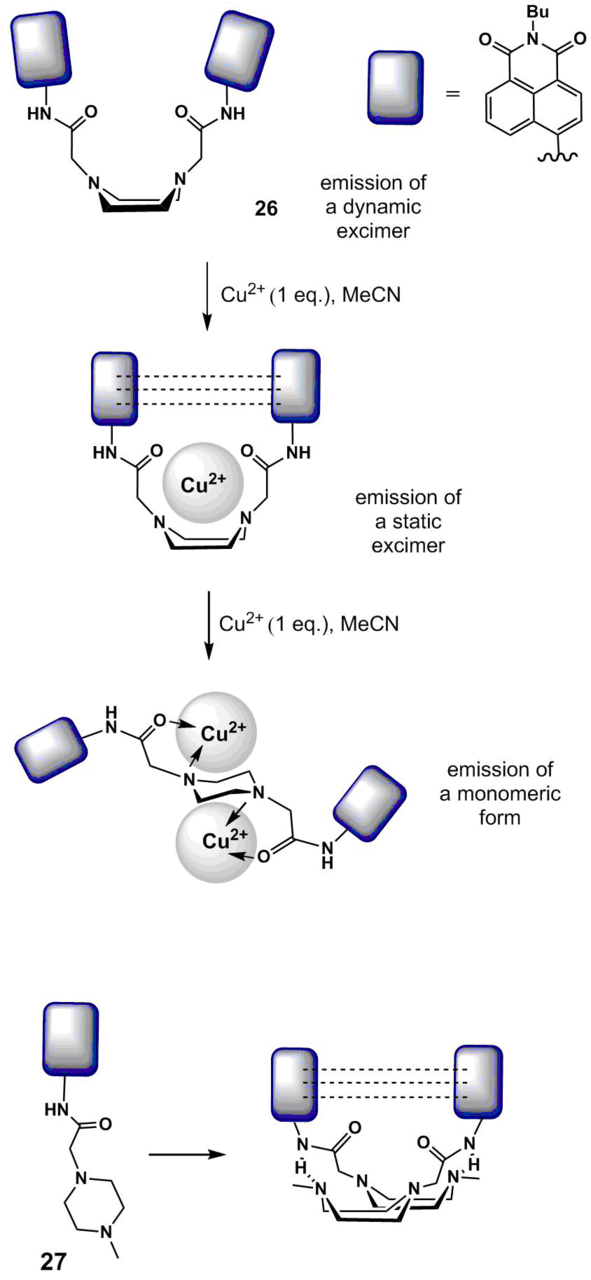

Xu et al. [65] developed fluoroionophore 26 (Scheme 8) that contains two acylaminonaphthalimide residues connected by a piperazine bridge. In polar solvents, 26 displays two fluorescence bands with the maxima at 450 and 550 nm which refer to the monomer form and dynamic excimer, respectively. The excimer results from the interaction of the excited and unexcited naphthalimide chromophores, which is possible when the piperazine ring is in a boat conformation (dotted lines in Fig. 8 show the stacking interaction in the ground state). The addition of one equivalent of Cu2+ ions to a solution of 26 in acetonitrile afforded a complex of 1:1 composition, which was accompanied by the broadening and bathochromic shift of the absorption band of 26, indicating the aggregation of the chromophores in the ground state owing to the stacking interaction and formation of a static excimer. At the same time, there were no changes in the fluorescence spectrum of the ionophore. The authors explained this by the fact that free ligand 26 in polar solvents demonstrates only fluorescence of the dynamic excimer which results from the naphthalimide transition to the excited state. The fluorescence of complex [(26):(Cu2+)] is caused by the emission of the static excimer; the emission spectra of the dynamic and static excimers are the same. A further increase in the copper ion concentration led to a reduction in the fluorescence signal of the static excimer with the simultaneous growth of the emission intensity of the monomeric naphthalimide chromophore at about 450 nm, which resulted in the formation of a complex of 1:2 composition [(26):(Cu2+)]. Sensor 26 demonstrated the higher selectivity towards copper ions compared to Li+, Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Cr3+, Ag+, Hg2+, and Pb2+ ions. An increase in the ratio of fluorescence intensities at 461 and 558 nm (I461/I558) enables the ratiometric measurement of the concentration of Cu2+ ions in aqueous solutions using 26.

Scheme 8

The introduction of N-methylpiperazine residue into the structure of 4-amino-1,8-naphthalimide was used to obtain ratiometric sensor 27 (Scheme 8) for the definition of the pH values of aqueous solutions [66]. Compound 27 contains only one naphthalimide residue but the intermolecular interaction of the amide group of one molecule of 27 and the nitrogen atom of the piperazine ring of the second molecule according to the authors' assumption is able to stabilize a boat-like conformation of the resulting bimolecular excimer. As a consequence, compound 27 has two maxima in the fluorescence spectra in the polar media: at 460 (monomer emission) and 560 nm (excimer emission). Compound 27 did not exhibit a spectral response to the presence of metal cations and anions of variable nature (including Cu2+ ions) in acetonitrile, which is explained by the existence of the above-mentioned intermolecular interaction that hampers the complexation. However, the ratio of fluorescence intensities of the monomer and excimer forms of 27 is sensitive to the pH value of aqueous solutions and the medium polarity, which allows one to use 27 as a pH sensor and to control the water percentage in organic solvents.

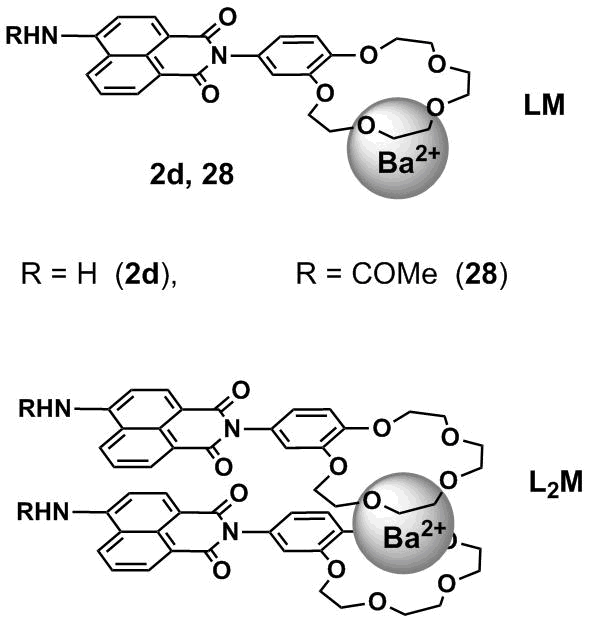

The formation of intermolecular excimer complexes was revealed upon the investigation of the binding of crown ether-containing 4-amino- and 4-amidonaphthalimides 2d and 28 (Fig. 14) with barium cations [25]. Since the size of a Ba2+ cation exceeds that of the cavity of benzo-15-crown-5 ether, the addition of a barium salt to the sensor solutions gives rise initially to the sandwich complexes of L2M composition stabilized by the π-stacking of the chromophores.

Figure 14. Complexes of 1:1 (LM) and 2:1 (L2M) composition of sensors 2d and 28 with barium cations.

At the significant excess of barium ions in solution, the sandwich complexes decompose with the formation of the complexes of LM composition (ligand/metal). In the case of compound 2d, the formation of the complexes of L2M composition was accompanied by the bathochromic shift and reduction in the intensity of fluorescence which allowed the authors to assume that the molecules in the complex are arranged similar to H-aggregates and the photoexcitation of L2M gives rise to the excimers. The light absorption by the complex molecules leads to the formation of excimers which can be evidenced by the appearance of a long-wave band in the emission spectra. It should be noted that the formation of the L2M complex in the case of sensor 2d was accompanied by the quenching of fluorescence of the free ligand, whereas for 28 the emission intensity increased. The differences in the spectral responses of ionophores were caused by the fact that while passing from N-amino derivative 2d to N-acetyl derivative 28 an electron transfer from the benzocrown ether moiety to the naphthalimide fluorophore is suppressed.

4. Application of other photophysical processes in the development of fluorescent sensors

In the last decade, many reports have been devoted to the optical sensors which response is caused by the changes in the charge, energy, and/or electron transfer efficiency upon binding with a substrate. At the same time, the dynamic development of supramolecular chemistry promoted the investigations on the sensors that utilize new mechanisms of variation of the optical properties upon binding. These mechanisms include the excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) [67] and aggregation-induced emission (AIE) [68]. Currently, there is only a limited number of examples of cationic sensors based on the chromophoric system of 1,8-naphthalimide that exploit the ESIPT and AIE mechanisms. However, these mechanisms deserve detailed consideration in this review since they have great potential for practical application.

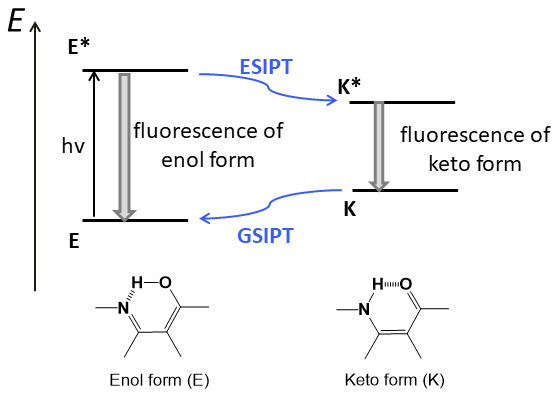

4.1. Excited state intramolecular proton transfer

To realize the ESIPT process, the presence of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between a proton donor group (NH or OH) and a proton acceptor moiety (С=O or N=С) is required [67, 69]. Figure 15 depicts an energy diagram for the ESIPT process for the molecules which in the ground state are in the enol form (E). The photoexcitation of these molecules causes the redistribution of electron density, which leads to an increase in the hydroxy proton acidity and strengthening of the basic character of the proton acceptor. Owing to this, a proton transfer occurs in the excited molecules with a high rate (< 10–12 s), which results in the tautomeric conversion of the excited enol form (E*) to the excited keto form (K*). After the emissive relaxation of K* to K, a reverse proton transfer, the ground state intramolecular proton transfer (GSIPT), occurs in the molecule. Fluorescence of the К* form appears to be often bathochromically shifted relative to the absorption of the initial molecule owing to the facts that the excited state К* has lower energy than Е* and the ground state К, in contrast, is higher on the energy scale (Fig. 15). The ESIPT process in the chromophores stabilized by the intramolecular hydrogen bond allows for exploring the molecules with the Stokes shifts ranging from 6000 to 12000 cm–1 [67].

Figure 15. Schematic diagram for the ESIPT process.

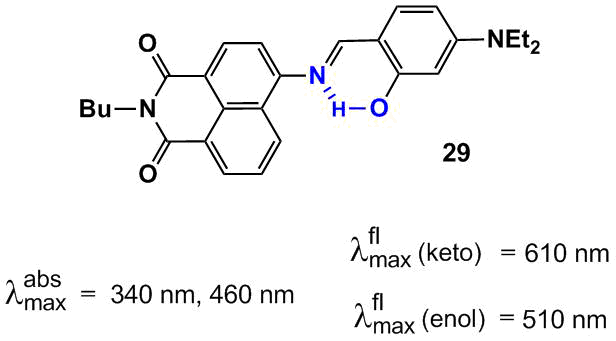

Since the protons of NH and OH groups in the ESIPT chromophores are acidic they can be removed under the action of a base. The resulting anionic form of the molecule will represent a bidentate ligand for metal cations. Thus, sensor 29 (Fig. 16), described in Ref. [70], demonstrates a spectral response to Al3+ and F– ions. The absorption spectrum of 29 shows two bands. The former located at 340 nm can be attributed to the π–π* type transition. The longer-wave band with a maximum at 460 nm is a charge transfer band from the diethylamino group located at the para-position of the styryl moiety of 29 to the carbonyl groups of the naphthalimide core. The presence of the salicylidene moiety with the ortho-arranged OH and imino groups provides the molecule with the ESIPT chromophore properties: upon photoexcitation, the dye molecule demonstrates dual emission at 510 and 610 nm that are responsible for the enol and keto forms of the compound, respectively (Fig. 15).

Figure 16. Structure of compound 29 and the normalized absorption and emission spectra of probe 29 in acetonitrile.

The quantum chemical calculation of the ground and excited states of tautomeric forms of 29 showed that the enol form in the S0 state is more stable than the keto form by 4.5 kcal/mol. In the S1 state, the keto form in which the phenyl ring and naphthalene core are arranged almost perpendicular to each other is more stable by 9.3 kcal/mol (C(NI)–N=C–C(Ph) dihedral angle upon twisting reduces from 153.64° for the enol form to 93.42°, NI is the naphthalimide moiety).

Compound 29 in an acetonitrile–water mixture (1:9, рН = 7.2) exhibits a selective response to aluminum cations; Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Ba2+, Cr3+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, and Ag+ do not hamper the definition of Al3+ ions. Upon addition of Al3+ ions, the absorption spectrum of 29 demonstrated an increase in the absorption intensity at 460 nm and a decline in the optical density in the region of a short-wave maximum at 340 nm. The variation of the intensities of both of the absorption bands of 29 upon interaction with Al3+ opens up the possibility for ratiometric measurement of aluminum ion concentrations in solution. The emission signal of 29 in the presence of Al3+ also undergoes essential changes: a new fluorescent signal arises in the range of 540 nm, the intensity of fluorescence of 29 in the range of 635 nm reduces, and the color of fluorescence emission of the solution changes from red to yellow. The level of detection of aluminum cations for 29 appeared to be 3.2∙10–8 М. The NMR and mass spectrometric studies showed that the spectral effects observed upon binding with Al3+ ions are explained by the decomposition of the Schiff base.

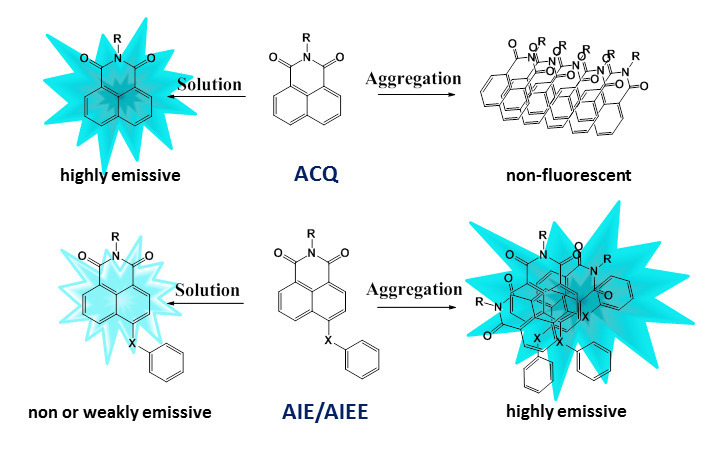

4.2. Aggregation-induced emission

Most of the organic luminophores represent planar conjugated structures that are prone to π-stacking interactions and the formation of aggregates [68]. Possessing intensive fluorescence in solution, these molecules form strong packing in solid state or upon weak solvation (Fig. 17), in which the fluorophore emission, in most cases, is effectively quenched since the non-emissive routes for relaxation of the excited states dominate. This effect is called the aggregation caused quench (ACQ) effect [71] and is mainly connected with the formation of H-type aggregates. The ACQ effect creates certain limitations for the practical application of luminophores, for example, as biosensors. In particular, the hydrophobic character of the fused aromatic rings in the luminophore structure often causes the dye aggregation in a biological medium, which is accompanied by luminescence quenching.

Figure 17. Illustration of the ACQ and AIE/AIEE processes.

In 2001, using 1-methyl-pentaphenyl derivatives of silole as the examples, a reverse phenomenon to the ACQ effect was revealed: the aggregation-induced emission (AIE) [72]. The AIE luminophores are not fluorescent in solution but afford intensive emission in a condensed state (Fig. 17). A modification of the AIE effect is the aggregation-induced emission enhancement (AIEE) [73]. The AIEE fluorophores emit with different efficiencies in all physical states: in solution, in the solid state, and in the form of aggregates. To date, it has been shown that the main reason for the emission intensification in a condensed state is the restriction of intramolecular motions. The structure of a typical AIE fluorophore contains a rigid rotator which rotation and vibrations are accomplished owing to the energy of photoexcitation of the molecule in the dissolved state. In the aggregated state, the rotation and vibrations are restricted and the emissive relaxation becomes predominant. It should be noted that this molecular moiety also must violate the molecule planarity, hampering the close packed arrangement of the fluorophores which would lead to the ACQ effect. The AIE effect is manifested not only on passing from a solution to a solid state but can also be induced by an increase in the medium polarity. In a more polar solvent, low-polar molecules start to form closely packed aggregates with a chaotic arrangement of the chromophores. In this state, the intramolecular rotations and vibrations are also suppressed.

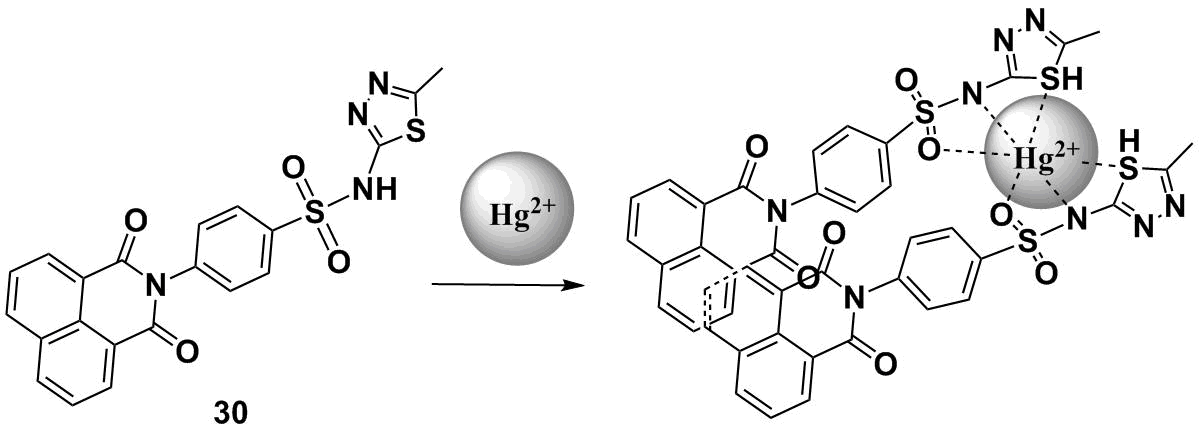

Scheme 9 depicts a structure of compound 30 that exhibits the AIEE effect in aqueous solutions [74]. The molecule of 30 is almost non-emissive in a DMSO–water mixture at the water content below 30 vol % [74]. An increase in the water content in a mixture leads to the gradual fluorescence enhancement of 30 at about 390 nm, which indicates the formation of fluorescent aggregates in solution. The binding of 30 with Hg2+ and Ag+ ions was studied in a DMSO–HEPES buffer mixture (1:99, v/v, рН = 7.2). An increase in the concentration of Hg2+ ions in solution led to a gradual reduction in the intensity of the emission band at 390 nm with the simultaneous appearance of a new fluorescence band with a maximum at 483 nm. The appearance of the new red-shifted emission band is explained by the formation of excimer particles in a solution of 30 which are stabilized by both the interaction of the receptor moiety of 30 with Hg2+ ions and π-stacking interaction of the naphthalimide cores of two molecules of 30 (Scheme 9). By the ratio of fluorescence intensities at 483 and 390 nm (I483/I390), chemosensor 31 can be used to measure the concentration of mercury cations in aqueous solutions.

Scheme 9

It should be noted that to date there are only a few examples of the application of the AIE effect in naphthalimide derivatives for the creation of chemosensors for metal cations. However, a range of the AIE naphthalimide luminophores continues to grow and we anticipate the production of ion-sensitive systems on their base. Below are considered a few examples of the naphthalimide derivatives which optical response is not caused directly by the AIE effect but they exhibit this effect in solution in the absence of cations.

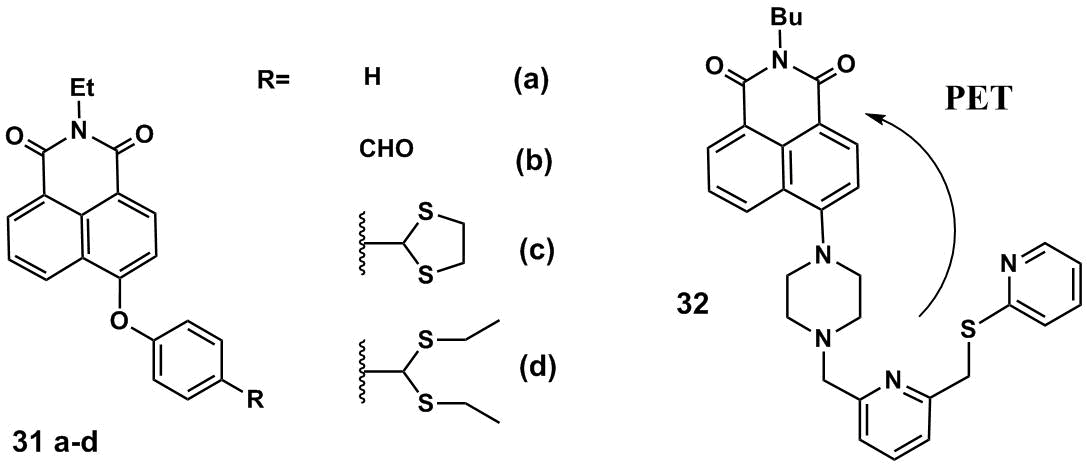

The structures of naphthalimide derivatives 31a–d which feature the AIE effect are presented in Fig. 18 [75]. The properties of the AIE luminophores are imparted by the specially selected substituents at the fourth position of the naphthalimide core. In compounds 31a–d, the naphthalimide core and phenyl ring of the substituents are arranged in different planes. These structures were called twisted "V"-shaped naphthalimides [75]. The quantum yields of fluorescence for a series of naphthalimides in THF reduce in the following order: 95.7% for 31a, 43.4% for 31b, and 9.2% and 6.2% for 31c and 31d, respectively. The nature of a substituent at the para-position of the phenol core of compounds 31a–d considerably affects the efficiency of fluorescence: the highest quantum yield is observed in the case of unsubstituted derivative 31а. At the same time, the introduction of conformationally labile thioacetyl groups leads to an essential reduction in the fluorescence quantum yields of 31c and 31d. At the concentration of 100 мМ, compound 31d forms aggregates already at the 20% content of water in THF. The aggregated phase emits 2.5 times more efficiently than a solution of 31d in THF, and the luminescence band is bathochromically shifted by 50 nm. As it was shown in this work, compound 31d exhibits the properties of a chemical dosimeter for mercury cations in a THF–H2O mixture (1:1, v/v). The interaction of 31d with Hg2+ ions leads to the elimination of the thioethyl groups and conversion of compound 31d to 31b, which is accompanied by fluorescence enhancement.

Figure 18. AIE luminophores 31a–d and 32.

Hg2+ cations in a THF–H2O mixture (1:1, v/v) can also be detected with compound 32 (Fig. 18) [76]. The optical response of 32 upon binding with Hg2+ is caused by the blocking of an electron transfer from the piperazine nitrogen atom of 32 as well as sulfur atoms. Chemosensor 32 displays selectivity towards mercury ions, the addition of Zn2+, Mn2+, Ba2+, Hg2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Pb2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Fe2+, Al3+, Ag+, Na+, and Li+ ions to a solution of 31 does not cause a significant fluorescence response. A possibility of application of 32 in living systems was successfully demonstrated on HeLa cells. The investigation of the efficiency of luminescence of 32 in a THF–water mixture showed that the molecule of 32 in solutions is relatively low polar and can relax in a non-emissive manner owing to the formation of non-fluorescent twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) states. In highly polar solvents, the AIE effect becomes predominant for 32 and the compound intensively emits. Hence, the authors of Refs. [75, 76] suggested new efficient turn-on chemosensors for mercury cations and extended a family of the AIE luminophores based on the 1,8-naphthalimide platform that can be used in fluorescence imaging.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the reports devoted to the creation of optical sensors for cations showed that this field is now of particular importance. The development of new systems for the detection of cations is dictated, first of all, by the necessity to perform in vitro and in vivo analysis. The 1,8-naphthalimide derivatives are widely used as the components of optical sensors; the most popular ones are those based on the 4-amino derivatives of naphthalimide which efficiently emit in the visible spectrum. In our opinion, the field of application of 1,8-naphthalimide fluorophores as the components of sensing devices will develop further in the following main directions: the production of naphthalimide derivatives which emission maxima will be shifted to the boundary between the visible and red spectrum regions, the application of new signaling mechanisms for the response generation, as well as the development of heterogeneous sensor materials.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, project no. 20-73-10186. The database studies were performed with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation.

References and notes

* HEPES buffer is based on a zwitterionic sulfonic acid buffering agent 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES).

† Tris-HCl is a solution of an organic buffering agent 2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol (Tris).

‡ The sensors that enter an irreversible chemical reaction with an analyte that leads to the product with the optical properties other than those of the initial ligand are called chemodosimeters.

§ The pseudo-Stokes shift is a difference between the donor absorption and acceptor emission wavelengths in a bis(chromophoric) system in which an energy transfer is realized.

- J. F. Callan, A. P. de Silva, D. C. Magri, Tetrahedron, 2005, 61, 8551–8588. DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2005.05.043

- B. Valeur, I. Leray, Coord. Chem. Rev., 2000, 205, 3–40. DOI: 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00246-0

- T. L. Mako, J. M. Racicot, M. Levine, Chem. Rev., 2019, 119, 322–477. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00260

- L. G. F. Patrick, A. Whiting, Dyes Pigm., 2002, 55, 123–132. DOI: 10.1016/S0143-7208(02)00067-0

- R. Stolarski, Fibres Text. East. Eur., 2009, 17, 91–95.

- S. Chen, P. Zeng, W. Wang, X. Wang, Y. Wu, P. Lin, Z. Peng, J. Mater. Chem. C, 2019, 7, 2886–2897. DOI: 10.1039/C8TC06163G

- L. X. Xiao, Z. Chen, B. Qu, J. Luo, S. Kong, Q. Gong, J. Kido, Adv. Mater., 2011, 23, 926–952. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201003128

- R. Tandon, V. Luxami, H. Kaur, N. Tandon, K. Paul, Chem. Rec., 2017, 17, 956–993. DOI: 10.1002/tcr.201600134

- S. Banerjee, E. B. Veale, C. M. Phelan, S. A. Murphy, G. M. Tocci, L. J. Gillespie, D. O. Frimannsson, J. M. Kelly, T. Gunnlaugsson, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2013, 42, 1601–1618. DOI: 10.1039/C2CS35467E

- N. Singh, R. Srivastava, A. Singh, R. K. Singh, J. Fluoresc., 2016, 26, 1431–1438. DOI: 10.1007/s10895-016-1835-y

- Y. Mao, K. Liu, L. Chen, X. Cao, T. Yi, Chem. Eur. J., 2015, 21, 16623–16630. DOI: 10.1002/chem.201502874

- P. A. Panchenko, O. A. Fedorova, Yu. V. Fedorov, Russ. Chem. Rev., 2014, 83, 155–182. DOI: 10.1070/RC2014v083n02ABEH004380

- R. M. Duke, E. B. Veale, F. M. Pfeffer, P. E. Kruger, T. Gunnlaugsson, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2010, 39, 3936–3953. DOI: 10.1039/B910560N

- X. Jia, Y. Yang, Y. Xu, X. Qian, Pure Appl. Chem., 2014, 86, 1237–1246. DOI: 10.1515/pac-2013-1025

- S. O. Aderinto, S. Imhanria, Chem. Pap., 2018, 72, 8, 1823–1851. DOI: 10.1007/s11696-018-0411-0

- M. Formica, V. Fusi, L. Giorgi, M. Micheloni, Coord. Chem. Rev., 2012, 256, 170–192. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.010

- P. Kucheryavy, G. Li, S. Vyas, C. Hadad, K. D. Glusac, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2009, 113, 6453–6461. DOI: 10.1021/jp901982r

- S. Saha, A. Samanta, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2002, 106, 4763–4771. DOI: 10.1021/jp013287a

- A. P. de Silva, H. Q. N. Gunaratne, J.-L. Habib-Jiwan, C. P. McCoy, T. E. Rice, J.-P. Soumillion, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 1995, 34, 1728–1731. DOI: 10.1002/anie.199517281

- A. S. Oshchepkov, M. S. Oshchepkov, A. N. Arkhipova, P. A. Panchenko, O. A. Fedorova, Synthesis, 2017, 49, 2231–2240. DOI: 10.1055/s-0036-1588712

- P. A. Panchenko, A. S. Polyakova, Y. V. Fedorov, O. A. Fedorova, Mendeleev Commun., 2019, 29, 155–157. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2019.03.012

- T. Chen, W. Zhu, Y. Xu, S. Zhang, X. Zhang, X. Qian, Dalton Trans., 2010, 39, 1316–1320. DOI: 10.1039/B908969A

- P. A. Panchenko, Y. V. Fedorov, O. A. Fedorova, J. Photochem. Photobiol., A, 2018, 364, 124–129. DOI: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.06.003

- P. A. Panchenko, N. V. Leichu, Y. V. Fedorov, O. A. Fedorova, Macroheterocycles, 2019, 12, 319–323. DOI: 10.6060/mhc190339p

- P. A. Panchenko, Y. V. Fedorov, V. P. Perevalov, G. Jonusauskas, O. A. Fedorova, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2010, 114, 4118–4122. DOI: 10.1021/jp9103728

- G.-H. Chen, W.-Y. Chen, Y.-C. Yen, C.-W. Wang, H.-T. Chang, C.-F. Chen, Anal. Chem., 2014, 86, 6843–6849. DOI: 10.1021/ac5008688

- H. Duan, Y. Ding, C. Huang, W. Zhu, R. Wang, Y. Xu, Chin. Chem. Lett., 2019, 30, 55–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.cclet.2018.03.016

- P. A. Panchenko, P. A. Ignatov, M. A. Zakharko, Y. V. Fedorov, O. A. Fedorova, Mendeleev Commun., 2020, 30, 55–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2020.01.018

- M. A. Zakharko, P. A. Panchenko, P. A. Ignatov, Y. V. Fedorov, O. A. Fedorova, Mendeleev Commun., 2020, 30, 332–335. DOI: 10.1016/j.mencom.2020.05.024

- S. Ghosh, Y. Chen, A. George, M. Dutta, M. A. Stroscio, Front. Chem., 2020, 8, 594. DOI: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00594

- Y. Tian, F. Su, W. Weber, V. Nandakumar, B. R. Shumway, Y. Jin, X. Zhou, M. R. Holl, R. H. Johnson, D. R. Meldrum, Biomaterials, 2010, 31, 7411–7422. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.023

- Y. He, Z. Li, Q. Jia, B. Shi, H. Zhang, L. Wei, M. Yu, Chin. Chem. Lett., 2017, 28, 1969–1974. DOI: 10.1016/j.cclet.2017.07.027

- Y. Fu, J. Zhang, H. Wang, J.-L. Chen, P. Zhao, G.-R. Chen, X.-P. He, Dyes Pigm., 2016, 133, 372–379. DOI: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.06.022

- M. H. Lee, N. Park, C. Yi, J. H. Han, J. H. Hong, K. P. Kim, D. H. Kang, J. L. Sessler, C. Kang, J. S. Kim, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2014, 136, 14136–14142. DOI: 10.1021/ja506301n

- A. Bigdeli, F. Ghasemi, S. Abbasi-Moayed, M. Shahrajabian, N. Fahimi-Kashani, S. Jafarinejad, M. A. Farahmand Nejad, M. R. Hormozi-Nezhad, Anal. Chim. Acta, 2019, 1079, 30–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.aca.2019.06.035

- L. Kang, Z.-Y. Xing, X.-Y. Ma, Y.-T. Liu, Y. Zhang, Spectrochim. Acta, Part A, 2016, 167, 59–65. DOI: 10.1016/j.saa.2016.05.030

- A. W. Czarnik, Proc. SPIE, 1992, 1648, 164–180. DOI: 10.1117/12.58297

- J.-W. Chen, C.-M. Chen, C.-C. Chang, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2017, 15, 7936–7943. DOI: 10.1039/C7OB02037F

- M. H. Lee, J. S. Kim, J. L. Sessler, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2015, 44, 4185–4191. DOI: 10.1039/C4CS00280F

- S.-H. Park, N. Kwon, J.-H. Lee, J. Yoon, I. Shin, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2020, 49, 143–179. DOI: 10.1039/c9cs00243j

- L. Wu, C. Huang, B. P. Emery, A. C. Sedgwick, S. D. Bull, X.-P. He, H. Tian, J. Yoon, J. L. Sessler, T. D. James, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2020, 49, 5110–5139. DOI: 10.1039/c9cs00318e

- C. G. dos Remedios, P. D. J. Moens, J. Struct. Biol., 1995, 115, 175–185. DOI: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1042

- Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd ed., J. R. Lakowicz (Ed.), Springer, Boston, 2006.

- P. A. Panchenko, Y. V. Fedorov, O. A. Fedorova, G. Jonusauskas, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2015, 17, 22749–22757. DOI: 10.1039/c5cp03510d

- B. Dong, X. Song, C. Wang, X. Kong, Y. Tang, W. Lin, Anal. Chem., 2016, 88, 4085–4091. DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00422

- W. Luo, H. Jiang, X. Tang, W. Liu, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2017, 5, 4768–4773. DOI: 10.1039/C7TB00838D

- X. Zhou, F. Su, H. Lu, P. Senechal-Willis, Y. Tian, R. H. Johnson, D. R. Meldrum, Biomaterials, 2012, 33, 171–180. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.053

- J. Wen, P. Xi, Z. Zheng, Y. Xu, H. Li, F. Liu, S. Sun, Chin. Chem. Lett., 2017, 28, 2005–2008. DOI: 10.1016/j.cclet.2017.09.014

- P. Mahato, S. Saha, E. Suresh, R. Di Liddo, P. P. Parnigotto, M. T. Conconi, M. K. Kesharwani, B. Ganguly, A. Das, Inorg. Chem., 2012, 51, 1769–1777. DOI: 10.1021/ic202073q

- Q. Cai, T. Yu, W. Zhu, Y. Xu, X. Qian, Chem. Commun., 2015, 51, 14739–14741. DOI: 10.1039/C5CC05518K

- J. Tang, S. Ma, D. Zhang, Y. Liu, Y. Zhao, Y. Ye, Sens. Actuators, B, 2016, 236, 109–115. DOI: 10.1016/j.snb.2016.05.144

- C. Liu, X. Jiao, S. He, L. Zhao, X. Zeng, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2017, 15, 3947–3954. DOI: 10.1039/C7OB00538E

- C. Chen, X. Li, X. Xie, F. Chang, M. Li, Z. Zhu, Anal. Methods, 2016, 8, 4272–4276. DOI: 10.1039/c6ay00933f

- Z. Xu, S. J. Han, C. Lee, J. Yoon, D. R. Spring, Chem. Commun., 2010, 46, 1679–1681. DOI: 10.1039/B924503K

- C. Yu, L. Chen, J. Zhang, J. Li, P. Liu, W. Wang, B. Yan, Talanta, 2011, 85, 1627–1633. DOI: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.06.057

- С. Wang, D. Zhang, X. Huang, P. Ding, Z. Wang, Y. Zhao, Y. Ye, Sens. Actuators, B, 2014, 198, 33–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.03.032

- J. Song, M. Huai, C. Wang, Z. Xu, Y. Zhao, Y. Ye, Spectrochim. Acta, Part A, 2015, 139, 549–554. DOI: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.12.073

- J. Fan, M. Hu, P. Zhan, X. Peng, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2013, 42, 29–43. DOI: 10.1039/C2CS35273G

- D. Cao, L. Zhu, Z. Liu, W. Lin, J. Photochem. Photobiol., C, 2020, 44, 100371. DOI: 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2020.100371

- C. Wang, D. Zhang, X. Huang, P. Ding, Z. Wang, Y. Zhao, Y. Ye, Talanta, 2014, 128, 69–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.03.073

- J. Fan, P. Zhan, M. Hu, W. Sun, J. Tang, J. Wang, S. Sun, F. Song, X. Peng, Org. Lett., 2013, 15, 492–495. DOI: 10.1021/ol3032889

- M. Kumar, N. Kumar, V. Bhalla, H. Singh, P. R. Sharma, T. Kaur, Org. Lett., 2011, 13, 1422–1425. DOI: 10.1021/ol2001073

- S.-k. Yao, Y. Qian, Z.-q. Qi, C.-g. Lu, Y.-p. Cui, New J. Chem., 2017, 41, 13495–13503. DOI: 10.1039/C7NJ02814H

- B. Valeur, Molecular Fluorescence. Principles and Applications, Wiley, Weinheim, 2001.

- Z. Xu, J. Yoon, D. R. Spring, Chem. Commun., 2010, 46, 2563–2565. DOI: 10.1039/c000441c

- N. I. Georgiev, P. V. Krasteva, V. B. Bojinov, J. Lumin., 2019, 212, 271–278. DOI: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2019.04.053

- J. E. Kwon, S. Y. Park, Adv. Mater., 2011, 23, 3615–3642. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201102046

- P. Gopikrishna, N. Meher, P. K. Iyer, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10, 12081–12111. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.7b14473

- L. Wilbraham, M. Savarese, N. Rega, C. Adamo, I. Ciofini, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2015, 119, 2459–2466. DOI: 10.1021/jp507425x

- G. Kumar, I. Singh, R. Goel, K. Paul, V. Luxami, Spectrochim. Acta, Part A, 2021, 247, 119112. DOI: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.119112

- J. Mei, Y. Hong, J. W. Y. Lam, A. Qin, Y. Tang, B. Z. Tang, Adv. Mater., 2014, 26, 5429–5479. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201401356

- J. Luo, Z. Xie, J. W. Y. Lam, L. Cheng, H. Chen, C. Qiu, H. S. Kwok, X. Zhan, Y. Liu, D. Zhu, B. Z. Tang, Chem. Commun., 2001, 1740–1741. DOI: 10.1039/B105159H

- B.-K. An, S.-K. Kwon, S.-D. Jung, S. Y. Park, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 14410–14415. DOI: 10.1021/ja0269082

- M. Bahta, N. Ahmed, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A, 2020, 391, 112354. DOI: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112354

- S. Mukherjee, P. Thilagar, Chem. Commun., 2013, 49, 7292–7294. DOI: 10.1039/c3cc43351j

- H.-I. Un, C.-B. Huang, C. Huang, T. Jia, X.-L. Zhao, C.-H. Wang, L. Xu, H.-B. Yang, Org. Chem. Front., 2014, 1, 1083–1090. DOI: 10.1039/c4qo00185k